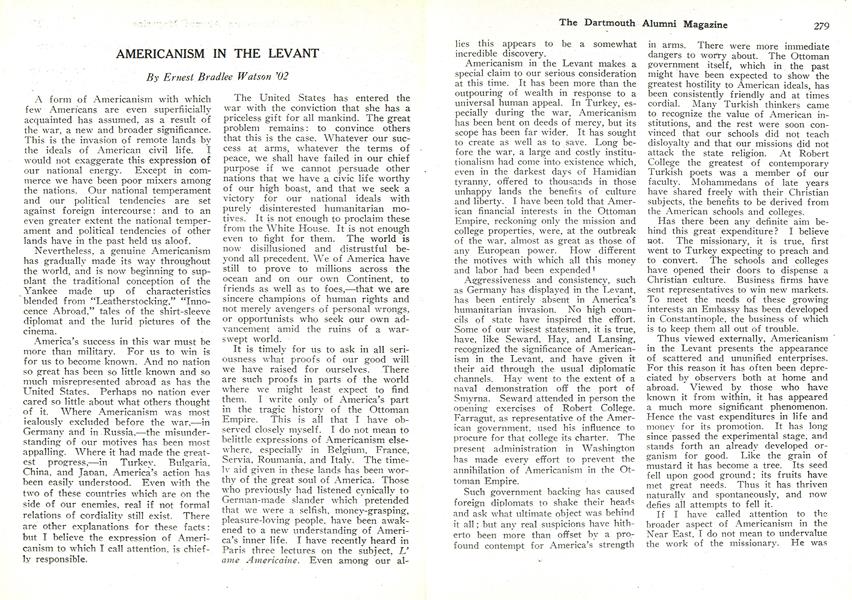

A form of Americanism with which few Americans are even superficially acquainted has assumed, as a result of the war, a new and broader significance. This is the invasion of remote lands by the ideals of American civil life. I would not exaggerate this expression of our national energy. Except in commerce we have been poor mixers among the nations. Our national temperament and our political tendencies are set against foreign intercourse: and to an even greater extent the national temper ament and political tendencies of other lands have in the past held us aloof .

Nevertheless, a genuine Americanism has gradually made its way throughout the world, and is now beginning to supplant the traditional conception of the Yankee made up of characteristics blended from "Leatherstocking, "Innocence Abroad," tales of the shirt sleeve diplomat and the lurid pictures of the cinema.

America's success in this war must be more than military. For us to win is for us to become known. And no nation so great has been so little known and so much misrepresented abroad as has the United States. Perhaps no nation ever cared so little about what others thought of it. Where Americanism was most jealously excluded before the war,—in Germany and in Russia, the misunderstanding of our motives has been most appalling. Where it had made the greatest progress,—in Turkey. Bulgaria. China, and Jaoan, America's action has been easily understood. Even with the two of these countries which are on the side of our enemies, real if not formal relations of cordiality still exist. There are other explanations for these facts: but I believe the expression of Americanism to which I call attention, is chiefly responsible.

The United States has entered the war with the conviction that she has a priceless gift for all mankind. The great problem remains: to convince others that this is the case. Whatever our success at arms, whatever the terms of peace, we shall have failed in our chief purpose if we cannot .persuade other nations that we have a civic life worthy of our high boast, and that we seek a victory for our national ideals with purely disinterested humanitarian motives It is not enough to proclaim these from the White House. It is not enough even to fight for them. The world is now disillusioned and distrustful be yond all precedent. We of America have still to prove to millions across the ocean and on our own Continent, to friends as well as to foes, that we are sincere champions of human rights and not merely avengers of personal wrongs, or opportunists who seek our own advancement amid the ruins of a warswept world.

It is timely for us to ask in all seriousness what proofs of our good will we have raised for ourselves There are such proofs in parts of the where we might least expect to find them. I write only of America s part in the tragic history of the Ottoman Empire. This is all that I have observed closely myself. I do not mean to belittle expressions of Americanism elsewhere, especially in Belgium. France, Servia, Roumania, and Italy. The timely aid given in these lands has been worthy of the great soul of America. Those who previously had listened cynically to German-made slander which pretended that we were a selfish, money-grasping, pleasure-loving people, have been awakened to a new understanding of America's inner life. I have recently heard m Paris three lectures on the subject, L ame Americaine. Even among our a lies this appears to be a somewhat incredible discovery.

Americanism in the Levant makes a special claim to our serious consideration at this time. It has been more than the outpouring of wealth in response to a universal human appeal. In Turkey, especially during the war, Americanism has been bent on deeds of mercy, but its scope has been far wider. It has sought to create as well as to save. Long before the war, a large and costly institutionalism had come into existence which, even in the darkest days of Hamidian tyranny, offered to thousands in those unhappy lands the benefits of culture and liberty. I have been told that American financial interests in the Ottoman Empire, reckoning only the mission and college properties, were, at the outbreak of the war, almost as great as those of any European power. How different the motives with which all this money and labor had been expended'

Aggressiveness and consistency, such as Germany has displayed in the Levant, has been entirely absent in America's humanitarian invasion. No high councils of state have inspired the effort. Some of our wisest statesmen, it is true, have, like Seward, Hay, and Lansing, recognized the significance of Americanism in the Levant, and have given it their aid through the usual diplomatic channels. Hay went to the extent of a naval demonstration off the port of Smyrna. Seward attended in person the opening exercises of Robert College. Farragut, as representative of the American government, used his influence to procure for that college its charter. The present administration in Washington has made every effort to prevent the annihilation of Americanism in the Ottoman Empire.

Such government backing has caused foreign diplomats to shake their heads and ask what ultimate object was behind it all; but any real suspicions have hitherto been more than offset by a profound contempt for America's strength in arms. There were more immediate dangers to worry about. The Ottoman government itself, which in the past might have been expected to show the greatest hostility to American ideals, has been consistently friendly and at times cordial. Many Turkish thinkers came to recognize the value of American institutions, and the rest were soon convinced that our schools did not teach disloyalty and that our missions did not attack the state religion. At Robert College the greatest of contemporary Turkish poets was a member of our faculty. Mohammedans of late years have shared freely with their Christian subjects, the benefits to be derived from the American schools and colleges.

Has there been any definite aim behind this great expenditure? I believe not. The missionary, it is true, first went to Turkey expecting to preach and to convert. The schools and colleges have opened their doors to dispense a Christian culture. Business firms have sent representatives to win new markets. To meet the needs of these growing interests an Embassy has been developed in Constantinople, the business of which is 12 keep them , all out of trouble.

Thus viewed externally, Americanism in the Levant presents the appearance of scattered and ununified enterprises. For this reason it has often been depreciated by observers both at home and abroad. Viewed by those who have known it from within, it has appeared a much more significant phenomenon. Hence the vast expenditures in life and money for its promotion. It has long since passed the experimental stage, and stands forth an already developed organism for good. Like the grain of mustard it has become a tree. Its seed fell upon good ground; its fruits have met great needs. Thus it has thriven naturally and spontaneously, and now defies all attempts to fell it.

If I have called attention to the broader aspect of Americanism in the Near East, I do not mean to undervalue the work of the missionary. He was the first on the field and he has been the most loyal and perhaps the most widely influential promoter of American ideals in the Levant. It is not surprising that his aims and methods at present vary widely from those of the few brave workers who fought their way against prejudice and fanaticism with the gospel of 1830. The problem of promoting Christian culture in Turkey, although more complex and baffling, was essentially the same as that of its advancement in America. Those who have been nurtured on the cant that a missionary is a creature with a queer hat, a Bible, and a hymn-book might indeed be surprised to step into a present-day mission at Aintab, Harpoot, Marsovan, or Adana. Great schools and colleges have developed out of the earlier gospel stations much as the modern Dartmouth has come forth from Moore's Charity School for the conversion of Indians. Mohammedan and Christian are admitted upon an equal footing. The instruction has been made practical, and is calculated to meet the needs of the communities for which the institutions exist. As in America, the mechanical arts, agriculture, business, and even engineering are gradually entering the curricula.

These schools and colleges, however, have not lost their religious character to the same extent as American institutions of learning. It would be a pity if such were the case. In America the college is but one of a large number of spiritualizing influences. In Turkey it is likely to be the only one. Hence the importance of religious education for students brought up in an environment of superstition and formalism, from which the element of idealism has all but vanished. Often a parent will tell us that he brings his son to get "American morality."

There are" indeed Armenian and Greek schools and churches under, the Orthodox Patriarch and the Gregorian Catholicos. Considering their opportunities the priesthood of the native communities is far from contemptible. Too often our American workers have ignored these forces and in turn have been ignored by them. Fortunately influences bringing them together have multiplied. They have become more mutually confident and dependent. During this time of unmatched suffering the American missionary is working whole-heartedly with the village priests', in the distribution of relief. I have even heard some missionaries say that the old methods of proselyting from the native to the Protestant denominations must be abandoned. In any case a better understanding and a more effective co-operation must result. Perhaps the great Mohammedan question itself will some day find its natural solution as the result of some such genuine fellowship among workers both within and without its seemingly impenetrable barriers, if only these workers may have at heart a pure zeal for the uplift of humanity.

Apart from the distinctly missionary activity in Turkey, a number of colleges have developed to meet the demand on all sides for a higher education. Some of these were originally mission stations. Others, like Robert College, were never connected directly with any mission. The most notable of these non-missionary institutions are Robert College, the Syrian Protestant College, and the American College for Girls, now known as Constantinople, College. In all respects these resemble privately endowed institutions in America, and every year the resemblance becomes more complete. They are undenominational and in a large measure self-supporting. One of them, the Syrian Protestant College, is incorporated as a university. Robert College, which gives its degrees under the Regents of New York, although not a university in any sense, has an excellently equipped school for mechanical and electrical as well as civil engineering. Just before the war, the American College for girls moved into a magnificent new plant designed and constructed by the best American architects and builders. All three of these institutions are situated upon sites of unsurpassed beauty. They are an imposing testimony to the broad humanitarianism and unstinted generosity which America has lavished upon the peoples of the Near East. I once heard Sir William Ramsey describe these institutions as the most perfect expression of America's "practical idealism." The description is a good one, but in the light of recent events these colleges have come to mean far more. They stand before the people of the Levant as the pledge of that great faith in the fellowship of humanity with which America has entered the war.

The present attitude of both Turkey and Bulgaria towards the United States is an interesting indication that this is so. Although Turkey has broken relations with Washington the break has been only formal. The Turkish government continues to show every courtesy towards these schools, and Turkish students are still permitted to attend them. Special provision has from time to time been made for food maintenance. Some elements in the government, it is true, have opposed them and threatened them with seizure. Those highest in authority, however, have recognized the value of these institutions as symbols. The great body of the Ottoman —Turks as well as Christians—feel that if these colleges are closed, the door will be definitely and perhaps forever shut upon a great and genuine friendship— not of nation" to nation—but of man to man.

Similarly Bulgaria, in spite of pressure from her great ally, and even from the Entente and from circles in America as well, remains both formally and in reality a friend of the United States. Her minister in Washington, appointed only a few weeks before the outbreak of the war, is the only remaining representative of the Central Powers at our Capital. Those who clamor for his dismissal fail to realize the very genuine friendship which the Bulgarian people as a whole have felt for America because of the education of their leaders at Robert College, and because of the part played by this institution and by American diplomats in giving to the world the first true account of the horrors of the Bulgarian atrocities. As a result of the widespread indignation thus aroused against her despoilers. Bulgaria became a principality and later an independent state. Bulgarians have come to regard America as a great and benign friend. It was therefore a most significant fact that the first Bulgarian representative, the present minister to Washington, was not only an alumnus of Robert College, but also a member of its faculty. A more appreciative and sincere friend of America could hardly have been found. There is not a more significant fact in America's diplomacy during the war than this continued friendship between a little country struggling, as she firmly believes, for her existence, and her great forbearing friend six thousand miles away.

Let me assure those who still doubt the wisdom of this indulgence that so long as Stephen Panaretoff is Bulgaria's representative, this bond of friendship will not be violated because of diplomatic abuse. If it should be broken by our government, a useless act would have been committed. If Bulgaria herself is forced by her allies to break it, let us even then not make the mistake of imputing the change to her own better judgment or to her forgetfulness of the old allegiance.

In the stress of war, Americanism has had to depart widely from its former course. Where before it was building on a large scale, it must now be content to exist and to save. What effort it is now able to put forth aims chiefly to spare life that the Christian populations of the Ottoman Empire may not be exterminated. This great and at times almost hopeless labor has gone on quietly and almost unobserved by a world too busy elsewhere to note or even to care, when the most frightful human suffering of which the world shows any record is still in progress and unchecked. Our Red Cross, our embassy, our schools, and our missions have united in this great work of rescue. Three figures have stood out above all others in this desperate labor, those of our last two ambassadors, Mr. Morgenthau and Mr. Elkus, and that of the. manager of the American Board of Foreign Missions in Turkey, Mr. William Peet. It seems as if these men' had been raised up by a special providence for this task, and their achievements, both in diplomacy and in the ministrations of common humanity will long remain landmarks to attest the genuineness of the American attitude towards all peoples.

Those who are devoting their lives to work in the Near East,—and not a few of them owe allegiance to Dartmouth,— look forward to the time when war shall forever be banished from "these bloodstained lands. I dare not prophesy. The fate of the world is still too much in the balance for anyone to sketch the map of the future, or to foresee the form of government which will have sway. One fact, however, stands out from the midst of chaos. America has, within the limits of the possible, remained loyal to her great task of civilization in the Levant. Her service has been rendered devotedly and with no thought whatever of reward. Few human hearts in these Eastern lands remain unconvinced that in America they have a great friend upon whom they may count not only to help them in the hour of distress, but also in the days of reconstruction which are to follow.

A great English statesman once foretold that America would solve the problem of the Near East. It is too early yet to say whether this prophecy will be fulfilled in any political sense or not. There can be little doubt, however, that the Americanism of the Levant which I have attempted to describe, will prove a decisive factor in determining the nature of the final settlement. There lies before us an unparalleled opportunity to assist at the resurrection of various ancient civilizations, especially the Armenian, the Greek, the Ottoman, and the Bulgar Slav, peoples that for centuries have been the slaves of intrigue, petty ambition, and unspeakable savagery and lust. When our part in the present tragedy is finally and honestly told, we shall stand acquitted before the nations of the imputation often flung at us that Americanism is only a form of money worship, and that, were the opportunity open to us, we too would stalk martially on the road to empire.

Many in the Levant that once distrusted us, now know the genuineness of our proffered friendship, and they will turn to Americanism as they might to the sunlight or to clear water, for the means of their new life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleMr. Watson's article in this number of the MAGAZINE on "Americanism

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleTWO LETTERS FROM THE FRONT

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleDEATH OF LIEUTENANT EADIE '18

April 1918 By FRANK N. HUME -

Article

ArticleNOTES

April 1918

Ernest Bradlee Watson '02

Article

-

Article

ArticleCHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION

August, 1914 -

Article

ArticleSUMMER MILITARY CAMP AT WILLIAMS

May 1918 -

Article

ArticleProf. Wilson Given Oxford Award for Book on Diderot

February 1954 -

Article

Article"The Turkevich Team"

June 1960 -

Article

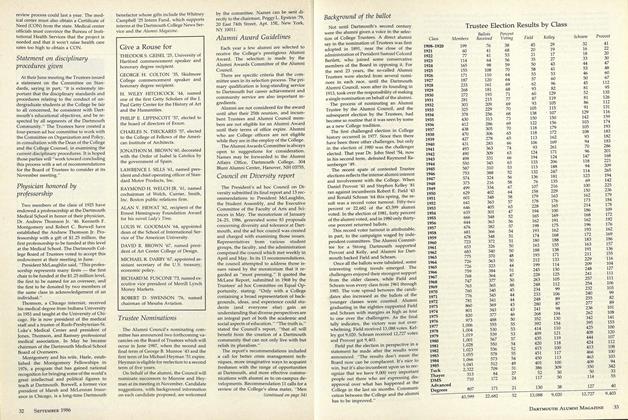

ArticleStatement on disciplinary procedures given

September 1986 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S ALMANACK

NOVEMBER 1988