It may seem strange to speak of the professor in our colleges and universities as a "religious problem," but the statement is not of our own phrasing. From many quarters recently the evidence has been coming in that we are being considered by the religious leaders of the day as a considerable problem. I say we, because though my department of Biblical Literature and History might seem to place me in a somewhat different position from the professor in mathematics or physics, yet this is only a seeming. Biblical History is an academic subject, and I am a college professor. Anything therefore that is said here applies to me as well as, I may think, it applies to professors in general. Here are some of the judgments offered in recent writings touching our religious character and influence.

"In too many cases the student Looks to the professor in vain for any assistance in his religious life."

"The student's moral and religious life is sometimes endangered, strange as it may seem, by the very studies which he pursues under the leadership of his various instructors."

"Students lose interest in all church and religious life when they have been in college a little while and the professor must bear a large part of the blame."

"The faculty is often quite benighted or smugly complacent of callous to the appeal of religion." When this statement was read to a clergyman in a college town he replied: "Alas, too seriously true."

"And yet I doubt if on the part of our faculty members in general, especially many of the younger members, there is a sufficient sense of religious opportunity and duty."

From Professor Leuba in his Book:

"The Belief in God and Immortality," has come recently what has perhaps been the most disturbing of these judgments. Professor Leuba conducted a scientific questionnaire, by means of which he secured what he considered dependable data, "concerning the beliefs in God and in immortality of college students and of several classes of men of high attainments." The latter classes include "the American scientists, historians, sociologists and psychologists." These are of course in the main our college and university professors. Two or three of the conclusions based upon these data are selected.

"The correlation shown, without exception, in every one of our groups between eminence and disbelief appears to me of momentous significance . . . . I do not see a.ny way to avoid the conclusion that disbelief in a personal God and in personal immortality is directly proportional to abilities making for success in the sciences in question . . . The students' statistics show that young people enter college possessed of the beliefs still accepted, more or less perfunctorily, in the average home of the land,, and that, as their mental powers mature and their horizon widens, a large percentage of them abandon the cardinal Christian beliefs. It seems probable that on leaving college, from 40 to 45 per cent of the students with whom we are concerned deny or doubt the fundamental dogmas of the Christian religion. . . . Parallel with the diffusion of knowledge and the moral qualities that make for eminence in scholarly pursuits . . . goes . . . the widespread rejection of the two fundamental dogmas of organized Christianity, i.e., the belief in God and in immortality."

These few opinions and judgments picked up at random evidently indicate that the college professor constitutes more of a religious problem than he is aware of. They open up a big question. Times of change and disturbance always bring intellectual leaders immediately to the fore. Since religion and education are so vitally related it is but natural that the professor's religious thought and life, as well as his intellectual, should come under consideration. The problem is not going to be settled at once. More questionnaires will doubtless be undertaken—with more scientific exactness. we hope than Professor Leuba's reveals. Statistics of items of belief, of attitudes towards certain vital questions, of church attendance and of changes the years may have made in religious outlook will be compiled. The program of a forthcoming national convention hints that the whole matter may be discussed. It may therefore not be out of place to state a few facts and convictions relative to it.

The first fact that stands out prominently is that the outer and the inner life of the professor are an open book these days. His strenuous daily work and not too excessive salary function with good motives, to produce a quiet, wholesome life. His thinking is known much more than ever before because he is realizing the social call of the hour and is writing, lecturing, and even preaching. His lectures and recitations are always open to visitors and students have always a permanent record of his wisdom and even of his views on important subjects or questions. There is nothing hidden that is not being revealed.

The attitude of professor and student, and graduate as well, toward the church as an institution and towards the dogmas, teachings and spirit of the organized church is of course the center of the modern criticism and question. It is well known that college graduates are not notable for their church activities and attendance. It does also seem to be true that church interest and attendance, where voluntary, decreases as the freshman leaves behind his vernal experiences. If it is true, as the statistics above quoted would indicate, that 40 to 45 per cent of students deny or doubt the fundamental dogmas of the Christian religion, this is surely cause for investigation and serious study. But in how far is the professor in his religious life and thinking responsible?

A rather cursory inquiry into our church attendance and interest here at Dartmouth leads to the conclusion that less than 10 per cent of the professors manifest a decidedly lukewarm attitude toward the church and its work. It may be too optimistic, but one may venture the opinion that this percentage might be found to be the general one among our colleges and universities when the 100 per cent attendance of the church-controlled institutions is averaged up with the lower percentages elsewhere. This fact with the additional one that a large number of men are very actively and influentially engaged in church work should carry considerable weight.

Very many professors as well as educated men everywhere do not accept or see the same truth and validity in some of the church dogmas and practices that church officials and preachers seem to see. But this must not be interpreted as showing unbelief: or lack of religion on the part of our educated men. There is a vital distinction to be made between religion and dogma on one hand; between religion and religious practices on another; and between a belief in God and immortality and certain expressions of this belief. Knowing as one should the diffidence of the modern professor to subscribe to a general undefined dogma or statement, we must subject Professor Leuba's conclusions to a critical test before reaching, as he does, such sweeping conclusions. It would seem that the discussion of this whole problem should take the form of a study of the comparative values of the positions held by the professor and those held by the so-called orthodox theologians.

The church and institutional religion in general are proverbially conservative. Perhaps if we could see far enough we should see that this quality in this sphere is essential. In the midst of the modern criticisms of conservatism, slowness and inefficiency, perhaps a good thesis could be made out to establish superior values in these failings. But religion, on the other hand, is a continually progressive urge and force which manifests itself not always in the naturally expected channels and places. It is stirring itself in -the church today as it has not had the chance for many years. It is expressing itself in the inmost heart of men today as it has not had the opportunity to do for some time previous. More men than before are interpreting the times sub specie aeternitatis and are feeling the glow and uplift of the higher touch upon their spirits. Some of our chaplains! at (the front express conditions there in terms which we may well apply at home; that is, that there is present now a surging undefined soul life which is calling for concrete expression. It would seem as if we must lay aside our pint measures and in openness of heart and mind pray that we miss not what wonderful things God is doing in wonderful ways in our day.

That this religious urge is concretely present and even obtrusively operative in our colleges and universities ought to be manifest even to the most casual observer. The spirit of honesty, the love and search for truth, the fearlessness and courage in seeking out truth, the sense of responsibility for the future of civilization and of religion, are surely the signs of the spirit. Then every science today finds its way sooner or later into the field of theology and religion. This is a tacit though often denied tribute to the place of superiority of religion in all studies. There is, however, but one conclusion to be drawn and that is that free and honest discussion and study by trained and truth-loving minds cannot but help along the cause of true religion.

When all this is said it does not mean that we are not conscious of. limitations and failings. The great temptations of the professor are to become too individualistic; to mistake intellectual abstractions for flesh and blood realities; to feel too exclusively the truth of a theory or an established thesis; to become narrow by self limitation for high proficiency in a chosen field; and in the realm of religion, and especially of Christianity, to make Christianity conform to our judgment and estimation instead of heeding the call to know the Great Leader first and be conformed by him into knowing the truth. These temptations shadow the life of intensified thinking and the balancing and making of judgments. Hence again may it be said that the times call for an honest, open, widespread evaluation of beliefs, convictions, dogmas, practices, and motives.

William Hamilton Wood, Phillips Professor of Biblical Literature

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

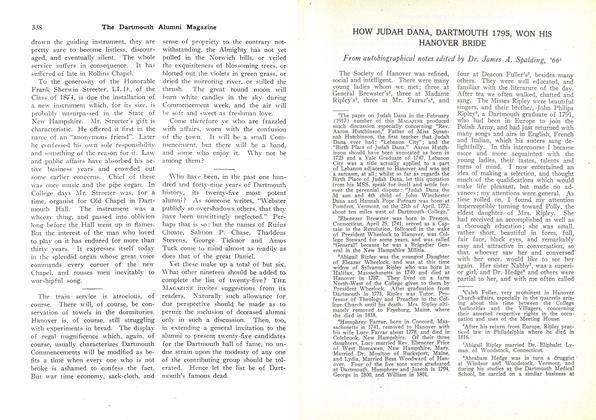

ArticleHOW JUDAH DANA, DARTMOUTH 1795, WON HIS HANOVER BRIDE

May 1918 By James A. Spalding, '66¹ -

Article

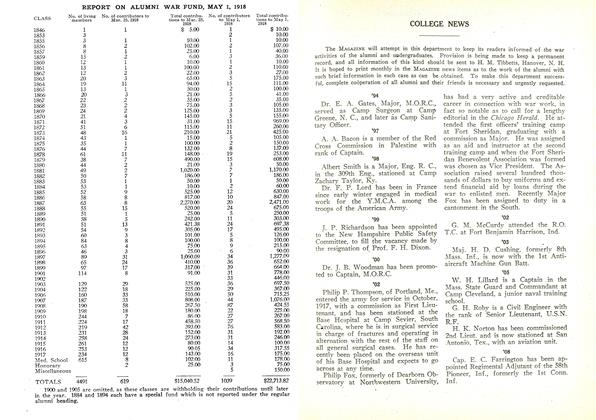

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

May 1918 -

Article

ArticleMARCH MEETING OF THE TRUSTEES—EXTRACTS FROM THE MINUTES

May 1918 -

Article

ArticleLETTER FROM LIEUTENANT J. C. REDINGTON '00

May 1918 -

Article

ArticleCAMPUS NOTES

May 1918 -

Article

ArticleSUMMER: NO LONGER A "VACATION" FOR THE DARTMOUTH STUDENT

May 1918