The following letter from Dr. Tucker was read by Mr. Edwin A. Bayley '85, President of the Dartmouth Alumni Association, at its dinner in Boston on March 5.

My dear Mr. Bayley:

I have been greatly interested in the program which you arranged for the present Dartmouth dinner in which you kindly invite me to have a part. My attention was especially arrested by your injunction, following the impressive list of the names of Dartmouth men in the service abroad, that we not only preserve the traditions of the College, but that we also "Keep the Faith." In asking myself just what the "Faith" of Dartmouth is, in the keeping of which we may serve the nation in the present juncture of affairs, my mind reverted to a crumpled sheet of paper that had been lying for some years in safe keeping in my desk — the original manuscript copy, partly in ink and partly in pencil, of Richard Hovey's ode to the country, on occasion of its venture into the world through the Spanish War. The Ode bears, as you will recall, the striking title of "Unmanifest Destiny" and is in itself at once a rebuke to that national conceit which was then finding expression in the popular doctrine of "Manifest Destiny," and a plea for faith in its as yet "Unmanifest Destiny." I quote the closing lines: —

"I do not know beneath what sky,Or on what seas shall be thy fate;I only know it shall be high,I only know it shall be great.''

To anyone familiar with the Ode, or to anyone reading it for the first time it will appear how "naturally it rises above the occasion which called it out and fits itself to the mightier issue of the present. It will also become evident just what Hovey meant by the faith which can give to the College or to the nation the sure access to its "Unmanifest Destiny." And we have only to turn to our own history to see just how it works. The two great events which we commemorate tonight show us that this faith reduced to practical terms, meant both to the founder and refounder of the College nothing more and nothing less than the power to adjust their minds to the greater issues that were to determine the fate of the College. That is what it must always mean — the power to adjust the mind to the greater issue as it arises.

We accord the founding of Dartmouth to the faith of Eleazar Wheelock. What was the supreme exercise of his faith? Dartmouth College as we know it was not in the first intention of Wheelock. His first purpose and his long-cherished project was his Indian School. That was "Manifest Destiny." For that he sent Samson Occom to England: for that he took his own way into the northern wilderness. He was then sixty years old, and apparently about to realize his life-long desire, when the scheme became impracticable because of its insufficiency. It was then that the faith of Wheelock really asserted itself in the power to readjust his mind to the new and greater issue hidden in the ''Unmanifesl [missing Text] conception. And it was then, because of his undaunted and discerning faith that as the mirage of his Indian School faded away, there rose in its place the substantial walls of Dartmouth College.

The refounding of the College is still more a proof of my definition of the historic faith we are enjoined to keep. Why is not Dartmouth College to-day a State University? Simply because Mr. Webster could not adjust his mind to that conception of its destiny. You may say that he could not shrink his mind to that conclusion, or you may say that such was the audacity of his faith that he would not harbor the thought. But the fact remains, that it was Mr. Webster's obedience to the dictate of his higher nature, though acting contrary to the general advice of men from other colleges in New England, and under protest from some who feared to put the charters of their own colleges to a final test, that he determined to cast the fortune of his College into the lap of the Supreme Court and take the result. We know the result. We know that by this mighty venture of his faith, he gave to all colleges the lasting security of their chartered rights, and that to us he gave back in place of an already established state institution a nationalized college, the significance of which return becomes more and more aPparent through the enrollment, in increasing numbers, of the sons of every other state from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

We can hardly fail to remind ourselves as the keepers of this historic faith that the time may come, may even be at which will test our power to ad- [missing text] to great educational issues which may vitally affect the College. I say no more at this point because of my firm confidence that whenever these issues present themselves they will be met with that breadth of view, and elevation of purpose, and boldness of approach which have already become characteristic of the present administration of the College.

But what of our attitude to the nation, the object of our immediate and urgent concern? Can we do better than to try to apply this injunction that we keep the faith in the sense in which I have tried to interpret it, as the power to adjust our minds to great issues as they arise? How constant and imperative has been the demand for the use of this power- in our recent history. To recur to Richard Hovey's figure — with what rapidity have we been forced out of the region of our "Manifest" into that of our "Unmanifest Destiny." For a century we lived in the security and pride of our isolation. That was our providential assignment among the nations. That was our "Manifest Destiny." It took but so slight a cause as the Spanish War to disabuse our minds of that fallacy, and adjust us to our place in the world.

Then came our experience of neutrality. That, we tried to persuade ourselves as we shrank from the horrors of war, was our "Manifest Destiny." Upon the high authority of our President we were assured for a time that this was to be our distinction. "We are," he said, "a mediating nation — the mediating nation of the world." This was a fit conception as applied to our internal life, that of mediating among the nations [missing text] which we are "compound [missing text] out as a theory of our relation to the warring peoples it soon became unsatisfying, then disheartening, then a burden intolerable to bear, an experience too bitter to endure., The day when we disowned our neutrality was a day of emancipation. And today the joy with which we welcome our returning sons is in part the expression of our gratitude for our deliverance at their hands from our abject condition into the community of the suffering but free and exalted nations.

And now we are entering upon another stage in the disclosure of our "Unmanifest Destiny." What part shall the nation take in the use of its sovereignty? Certainly this is a great issue, in the minds of many a very grave issue. But it is here, and how shall we meet it? I can only answer for myself. I cannot allow myself to believe that we shall put such a construction upon the doctrine of sovereignty as will block the way in the further advance toward the realization of our "Unmanifest Destiny." I believe rather that "We the People" will allow, and if need be, charge the nation, in the full [missing text] its sovereignty to [missing text] with the great sovereignty [missing text] the world in the positive and determined effort to maintain the rule of justice, order and peace. If a fellowship with this intent is to exist and we are not in and of it, where are we? If it shall not exist because we took no sufficient part in creating it, what answer shall we make to history for the relapse of the nations by consequence into the state of elemental warfare?

is my response,'too long and yet too brief, to the injunction that we keep the faith — the faith, that is, of the open, the courageous, the undistorted, the unconfused mind in the presence of great issues as they arise. This is the power as I apprehend, perhaps the greatest gift of our inheritance and the greatest discipline of our citizenship, through which we as the sons of Dartmouth and as loyal citizens of the state are to strive to fulfill the "Unmanifest Destiny" whether of the College or of the nation.

I am, in the fellowship of our faith, Most sincerely and heartily,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMILITARY NEWS

March 1919 -

Article

ArticleWILLIAM HOOD '67 Chief Engineer of the Southern Pacific Railroad Lines

March 1919 By Robert Fletcher -

Article

ArticleThe throaty contralto of the first robin

March 1919 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ROLL OF HONOR

March 1919 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF THE TRUSTEES MEETING

March 1919 -

Article

ArticleGIFT TO THE COLLEGE

March 1919

Article

-

Article

ArticleA WAH-HOO-WAH!

May 1939 -

Article

ArticleHow It Was Done in Hartford

April 1955 -

Article

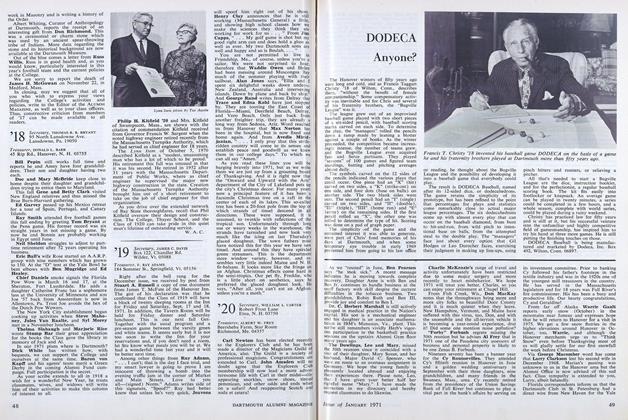

ArticleDODECA Anyone?

JANUARY 1971 -

Article

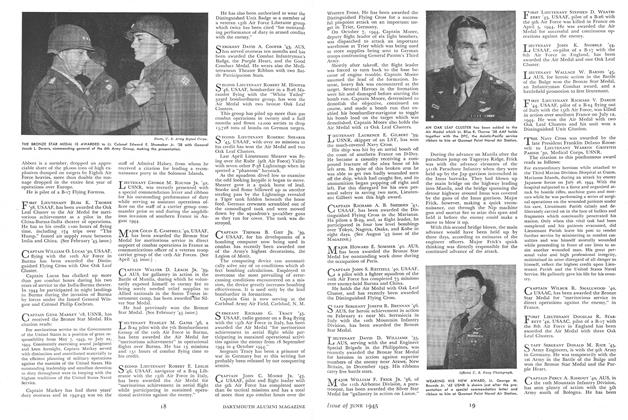

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleWe asked 53 students: "Would You Send Your Child to Dartmouth?"

June 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

November 1944 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22