body has led to the necessity of dividing the college for the purposes of chapel attendance. Rollins Chapel, although twice enlarged in the course of 25 years, is today inadequate to contain all the students at morning chapel exercises; and therefore recourse has been had to the expedient of having the freshmen attend such exercises either in Dartmouth Hall or in the College Church, while the three upper classes attend morning worship as usual in the chapel. This arrangement, while admittedly unsatisfactory, is beyond doubt the best solution possible in current circumstances. But it points the way to a serious discussion of the wisdom or practicability of retaining much longer the compulsory chapel attendance as a regular feature of the Dartmouth day.

Obviously the alternatives are not numerous. Either the college must have a much larger chapel, or must maintain two chapels, or must abandon all effort at compulsory chapel. The last mentioned is beyond question the easiest answer— and the least expensive. Whether or not it is the right answer strikes .us as doubtful and it might be a proper subject for general alumni discussion.

It is hardly to be assumed that the college will dwindle in size to the point at which this question would solve itself. The indications are quite the other way. The condition which confronts the college is therefore fairly to be considered permanent. The necessities incident to greatly increased numbers are pressing—possibly more pressing in other lines than this and to the point of working an unwelcome exclusion. Dormitories clearly must be had. Adequate boarding facilities are imperative. The need for a new library is a crying one. Is it, then, a reasonable probability that an adequate chapel will be readily forthcoming? Or must we face the disagreeable alternative of making chapel an optional exercise, with the forfeiture of certain advantages —more practical than spiritual in present conditions—which flow from getting the entire college up betimes in the morning and assembled in orderly concourse for the beginning of another day?

That a direct spiritual end is served by the morning ' chapel exercise may be doubted. The haste, the preoccupation due to pending tasks, above all the changing mental attitude of eventhoughtfuland mature worshippers, alike conspire to deprive the morning chapel service of any very deep religious significance. To abandon the service as a requirement would in itself be a confession that a decline of attendance was expected instantly to follow. Those who would come voluntarily to a religious service in the early morning would be a meagre fraction of the undergraduates, some impelled by a genuinely religious motive and some by a liking for the incidental music. It is 'certain that the inadequacy of our chapel accommodations could be met at once by abandonment of the present time-honored system. And yet one feels that it would be a lamentable forfeiture of an ancient grace.

Be the spiritual attitude of the present generation of college students what you will, it remains a fact that the chapel service has its manifold excuses for being. It gets the men up in good season; it brings them together conveniently for official observance and record; it enables the easy communication of needful notices to the entire student body; it starts the day right. Nor are the spiritual effects derived from hearing the Bible read, from common supplication, and from the music led by a noble organ to be despised or lightly thrown away. It would be rash indeed for this Magazine to assume to speak for the majority of alumni in such a matter; and yet the Magazine can hardly bring itself to believe that such majority would willingly see compulsory chapel attendance abandoned in favor of the optional system. It is fatally easy for men who have no early lectures to fall into the habits, of indolence; and if morning chapel does nothing more, it at least tends to forestall that.

It is therefore to be hoped that this may not be the alternative which the college will be forced to adopt as one consequence of its recent growth. Unquestionably the present size of the college does necessitate changes from many customs which obtained when the college was small, and this may be one of them. But it is not a thing to do in haste and certainly not one to do without mature deliberation and a weighing of all the elements involved. That it is a pressing problem, and one which will not wait many years for solution, seems clear. To this end it would be interesting if alumni opinion could be expressed.

Such problems as that presented by the college chapel may have their part in awakening us all to the disadvantages which infallibly attend bigness. Dartmouth has grown great and we are proud of it—but it is by no means an unadulterated blessing. For our increased size we have to pay, and some of the payment we shall find distasteful, one fears. That democracy which was once our boast—how shall we safeguard it against erosion? The intimate fellowship which was once as wide as the college is byway of becoming less wide even than the class, in a day when classes so far outnumber the whole college of a generation past. There was a certain prophetic insight in the poet who advised us more than a quarter-century ago to "set a watch lest the old traditions fail." They have not failed as yet—but with the augmented numbers the need for watchfulness has steadily increased.

There is invariably danger in extremes. Time was when Dartmouth was too small for either comfort or safety; the time cometh, and possibly now is, when the college is too great for either safety or comfort. It is well to recognize the positive evils, and not to dissemble or cloak them through motives of false pride, to the end that what endears Dartmouth to her children may not be forfeited in any tide of fancied success.

That which makes a college is not bricks and mortar, nor yet numerous students, nor yet a world-compelling faculty. It is an indescribable thing which perhaps one may call "soul" inherent in the entire organization—students, faculty, alumni, trustees, institutions, traditions, customs and the physical plant with which the work is done. There is such a thing as being too big for strength, especially when growth is unduly rapid. One may progress too fast for sustained progress. If we mistake not, the time is ripe for Dartmouth to take a sober account of stock, to make sure of the ancient landmarks, to set watch and ward against false ideals of education, to temper radical advancement with a saving tincture of conservatism. Conservatism may be overdone, as we all know;.but radicalism may also be overdone—and not all of us seem aware as yet of that reciprocal possibility.

The limits of a brief editorial are too circumscribed to admit of very extended discussion of the elective system, now so commonly overdone in American colleges, but the time evidently approaches in which this feature of the higher education must be taken up with serious intent to discover its proper metes and bounds. Every good thing is subject to abuse and nothing is clearer than that the abuses of the elective system, in institutions in which it has been carried too far, have led to: a serious impairment of what one may vaguely describe as "liberal education".

Much may said in these columns in the course of this coming year as to the appropriate place of specific requirements, common to all college students, which may be fairly regarded as essential in any scheme of education worthy to be denominated "liberal." For the moment it is sufficient to remind the reader that the unfettered election of courses by a student who probably has no definite idea as to his ultimate occupation in life is certain to lead to confusion and to prevent "liberal education" without conferring any benefit of technical, or professional, training to counterbalance the loss.

The old ideal of the American college was not vocational training, but a broad general introduction to "the humanities." This has no doubt required a certain alteration with the changing times; but it is questionable that the time has come entirely to forget the classics or those courses which to the so-called "practical" man appear more ornamental than useful. Whether or not Dartmouth should tend more and more to the production of efficient' workers in specific lines of gainful activity, or should renew her fealty to the older theories of fitting men for the richer enjoyment of life in the abstract, is a problem. Possibly it is an instance in which the middle course will be safest. The choice at bottom lies between keeping Dartmouth a college and making it a university.

Those of us whose life-work has concerned the writing of English will probably be among the first to deplore the trend away from Greek and Latin—languages commonly described as "dead", but known to all engaged in the realm of letters as most vitally alive so far as concerns their promotion of insight into the usages of our modern speech. It is difficult for such to admit any education to be genuinely "liberal" which denies the proper place of the Bible and the ancient classics in the scheme of things collegiate. Nevertheless, and on both sides of the Atlantic, the place of the classics has been disputed—starting with a defensible plea that the insistence laid upon (hem was too great and ending with the wholly indefensible assertion that there must in the end be no place for them at all.

It is evidently impossible to expect Dartmouth to revert to the full estate of a purely classical college, such as served well enough a generation or two ago. But it is at least hopeful that there will be no unconditional surrender to what our British brethren call "the mods". There lies before such a college a divided duty—a duty which demands not merely the sending into the world of an army of men trained as embryotic lawyers, or engineers, but also the provision of enlightened and honorable gentlemen, conscious of their inheritance from the ages as well as trained to contribute their mite to the generations yet to be. There is, or should be, more to a college education than a special fitness to earn one's living. There should be in it an element fitting one better to enjoy that living once it has been earned. To strike the accurate mean between the ancient and the modern lore is the great problem of our higher educators at the present time.

For some unworthy reason "culture" has seemed for several years to be suffering an eclipse, as if culture were something rather shamefaced and effete, with which America had no concern. Yet we must face the growth of a leisured class, and must in some way meet the requirement of it, so that leisure be enjoyed with dignity, being employed with ornament to itself and with benefit to the state. Of those to whom much is given much is required.

The MAGAZINE would hold a brief for the cultured American gentleman, feeling that there is in such a concept nothing for contempt and nothing inconsistent with a virile, efficient, constructive American citizenship. We are a part of all that we have met; and it is daily more evident that our newer civilization must take its place side by side with the older in solving the problems of this world. That we may show to advantage, not only in constructive ways but also in all others, may well be the devout American's prayer.

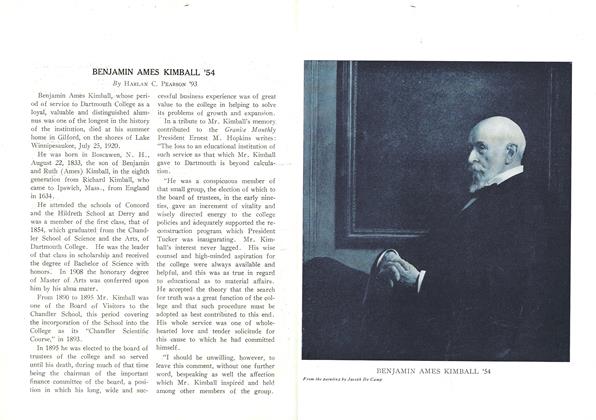

The College is the poorer by the recent deaths of Hon. Benjamin Kimball of Concord, long a trustee, and of Hon. Melvin O. Adams of Boston, one of the most loyal and interested of the alumni of the? institution. Both men had identified themselves so deeply with the college as to become virtually part and parcel of its fibre. Of Mr. Kimball's long and valuable service more detailed mention is made elsewhere. Of Mr. Adams' constant and active interest no one at all familiar with the energetic body of Boston alumni will require any reminders. It has been the fortune of the college to possess in the numerous graduates residing in and around the city of Boston a body fully alive to the concerns of Dartmouth and well qualified to give to those concerns an intelligent and solid support; and among those alumni it might be said that Melvin O. Adams was primus inter pares. It was largely through his promptness and energy that the Boston alumni were "summoned" to undertake the rebuilding of old Dartmouth Hall, while that venerable structure was still a smouldering ruin. It was largely because of the lively wit and genial good-fellowship of Mr. Adams that the annual alumni dinners at Boston were such jocund and brotherly events. No college is so rich in such sons that it can readily spare them and it was the hope that there might be vouchsafed to Mr. Adams as many years as Heaven had mercifully bestowed upon the venerable Mr. Kimball, with the certainty that lapse of time would intensify rather than diminish interest and zeal. In these men the college has lost devoted and wellbeloved adherents whose place in the scheme of Dartmouth things it will be difficult to supply. Commencements at Hanover will not be the same without the tall and venerable form of Mr. Kimball—and neither Hanover nor Boston gatherings will be the same without the handsome, good humored face and the eloquent tongue of Mr. Adams. But in this case the good that these men did lives after them; and in their respective degrees of contribution to the upbuilding of Dartmouth the college itself is in large measure the monument.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleADDRESS OF PRESIDENT ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS AT THE OPENING OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, SEPTEMBER 23, 1920

November 1920 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1920 By W. H EASTMAN -

Article

ArticleBENJAMIN AMES KIMBALL '54

November 1920 By HARLAN C. PEARSON '93 -

Class Notes

Class NotesREUNIONS CLASS OF 1870

November 1920 By A.S. ABERNETHY -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

November 1920 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1920 By WILLIAM SEWALL

Article

-

Article

ArticleFund Report

June 1952 -

Article

ArticleTuition Raised

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Article

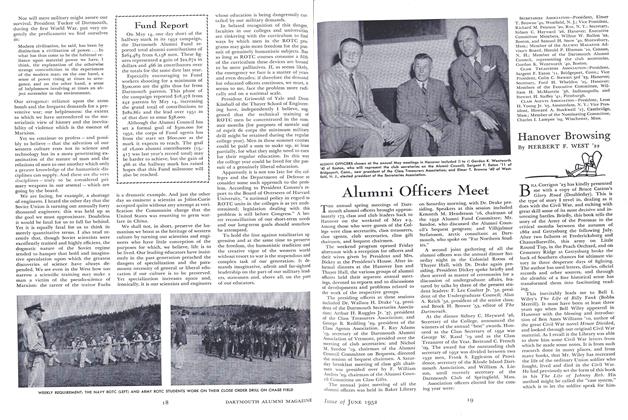

ArticleRuth Adams To Be Vice President

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Article

ArticleGraduate Awards

JULY 1972 -

Article

ArticleTHE PLACE OF MENTAL HYGIENE AT DARTMOUTH

February, 1922 By ARTHUR H. RUGGLES, M. D. '02 -

Article

ArticleClovers Bring Good Luck to Octogenarian

MARCH 1983 By Teri Allbright