The Grill Room in the basement of College Hall was comfortably filled for the annual dinner. The College proved a bountiful host and it was a satisfied group of secretaries who lighted their cigars and leaned back in their chairs for the after-dinner speaking. President Dana first called upon James H. Kimball, newly elected secretary of the Class of 1901, to speak upon the subject "Functions of the Class Secretary."

Mr. Kimball in his usual modest way disclaimed any worthiness or ability to speak with authority upon such a subject as had been assigned to him. He saw no reason why he, as the youngest secretary of the Association, should be called upon to elucidate such a subject unless it might in reality be looked upon in the nature of an initiation stunt. He said in part:

"The Functions of a Secretary—I did not know what it meant. Where could I quietly ferret out the desired information ? I turned to the dictionary and found that text books were available for the uninformed, but nowhere did I find information about the secretary. As is usual in such cases, my wife came to the rescue and suggested that I look through the class reports and see whether I could not glean from the reports of various classes the desired information. The suggestion seemed to be a good one and I became impressed with the idea that one of the chief functions of a secretary seemed to be that he must become a statistician like Babson. I went through first that excellent report which goes into detail about the doings of the Class of '68, and from that report I learned several interesting facts. I learned that the quality of liquor around Hanover in those days was such that abstainers had the advantage of the bibulous by eighteen years, and that an additional bonus of ten years could be had by refraining from tobacco. The men who drank liquor had lived at the rate of 1.4 years of the other men. I learned that two bachelors had died to every one married man. I learned that sixty percent of the eighty percent of the men in that class who were married had boys who were prospective Dartmouth men, and that ninty-five percent of the twenty percent who had no children believed that they could bring up the neighbor's children better. I learned that ninety-four percent of the lawyers eventually played golf and that eight percent spent their entire time at the links. I learned that seventy-five percent of all the doctors were poor chauffeurs, and that ninety-nine percent hated to see a baby born after midnight. I also found that one hundred percent of the ministers in any class were underpaid.

"I turned my attention now to see what I could glean from the members of my own class. I found that the men who had laid in a stock prior to January sixteenth were already beginning to see old age creeping upon them.. In addition, they were making flocks of influential friends daily. I found that ninety-five percent were opposed to the income tax. A very careful canvass of the class disclosed the deplorable fact that no one had sufficient sugar to help out the secretary. In addition to this, in the short time that I have been in office, I have found out that certain men seem to think that the secretary is paid a salary and that there is nothing that pleases him more than to be taken as an Information Bureau. A member from Cape Cod asked me to ascertain as to whether digging clams was at present considered as agriculture or fishing.

"However no man could come into the meeting of this Association and remain indifferent to the splendid spirit of cooperation and loyalty which permeates this Association. And as to the functions of the secretary? They are limited only to the individual and to the amount of time he is able to give to it. It may also be said to contain the duties and obligations of man to man in all his relations in life. If you could' determine, gentlemen, what are the functions of a friend, if you could determine the functions of a brother, or the functions of a man in his relations to a fellowman, you will have gathered together no more duties or functions than are already crowded together in the splendid work which you have been doing."

The next speaker was Professor Henry T. Moore, who spoke on the subject of "The Place of Intelligence Tests in the College". His remarks are quoted in part:

"The mental test, so-called, is practically a thing of the last twenty years and during that time development has been rapid. Scepticism about it has been justified because of the extravagant claims of some of the test makers. Nevertheless, some valuable results have emerged from the field of psychology during this period. Experience has shown with mathematical certainty that certain short tests do show surprising correspondence with what is known as "general intelligence". The ability to reach the right conclusion from a given set of facts, or to fill in omitted words, all have a twenty-year record back of them. Like the size of a man's vocabulary, or his ability to pass tests or examinations, these things have been shown to have a high degree of correspondence with a student's success in school. The success.of the army in its intelligence tests has naturally aroused the curiosity of the colleges about the rating of their own men. To date, exact statistics are available from six institutions concerning the comparative ratings of their students,—Dartmouth, Yale, Technology, Minnesota, Purdue and Brown. It may some time in the future be possible for every college to have an objective measure of its men by comparison with other colleges.

"What happens to these college men who have taken the tests? The present freshman class at Dartmouth averages 149 on a basis of 212. The lowest grade was 70 and that man was separated from college at the end of the semester for failure to do his work. Of the lowest ten men in the freshman class, only one has come through successfully. Records at Yale show that all under 105 had to be warned and only one-sixth of those above 105 needed this admonition. This experience is duplicated in the upper classes at Dartmouth. Phi Beta Kappa averages 177; the second year Tuck School men, who are picked for their scholarship, 172.

"The test may also be used in vocational guidance. If the student has extremely high intelligence ratings, he should be urged to take a full schedule of courses. By the same token, if a man makes only 75 and has an idea of entering a difficult professional school he ought to be cautioned as to whether his abilities can stand the experience. It would also be significant to give seniors some tests that they had as freshmen. This would give us a measure of a man's growth in College and furnish comparison by which one group may be weighed off against another to determine what the mental development has been, how his participation in athletics has affected him, whether the A. B. or the B. S. course seems to be more effective in producing mental ability, and what the effects of the use of tobacco may have upon his mental development.

"The time will doubtless come when every college will examine incoming freshmen and outgoing seniors according to standard intelligence tests. While these tests will not predict with absolute certainty a man's scholastic ability, they can serve as a means of comparison, and for this reason they should be advanced as fast as occasion warrants.

The last speaker was President Hopkins, who took as his subject, "Looking Forward."

He referred, in opening, to the early days of the Association when the objects to be attained were not so well-defined and the future rather hazy.

To quote: "The duties and responsibilities of the secretary have now crystallized and the secretaryship has come to be looked upon as the most honorable position in the gift of the class. The Association is doing for the College what the secretary is doing for his class.

"New and, until recently, unforeseen responsibilities have come upon the College. One of the most perplexing of these is its sudden and rapid growth. It is a truism that expansion in numbers almost always precedes expansion in resources. The expansion of numbers is already present. As a specific illustration, the highest number of applications for dormitory rooms from an incoming class on March first was last year, the figure being 155. This year on the twentieth of February the applications numbered 604. Were we free to take them, there would be an entering class at Dartmouth next year of several' times the number for whom accommodation can now be found. As it is, but a meagre proportion of those who apply can be admitted. Nor is this growth from any specific quarter. It is distributed in all sections. In the last freshman class 55 percent of the men came from west of the New England line."

The President then proceeded to show that the problem of restriction is not so simple as it might seem. More units might be required of a freshman or stricter examinations enforced, but in either case the College would debar men of high grade intelligence but technically ineligible. Action has recently been taken by the faculty which may offer a basis for intelligent restriction. This is the new plan for admission by which emphasis is laid on the quality of a student's preparatory work rather than on the quantity.

In closing President Hopkins said: "The problem of numbers means not merely additions to the present plant but practically its reduplication if even the present growth is to be accepted. The secretaries should have some knowledge of this situation because the answer to the fundamental question, 'What is the responsibility of the College?' is dependent upon the fiancial support that the College can find outside. Without this we have no right at all to grow. We cannot logically grow at the expense of the quality of work we have been doing or desire to do. We cannot grow at the expense of the instruction courses or at the expense of the teaching salary increases which ought to take place.

"I think it is the growing conviction that the instruction of the Dartmouth faculty and the isolated location of the College is something worth while. In every letter that conies in there is a reference to this. I believe at the present time, as never before, people are seeking those fundamental things which make up the worth of a college before any choice is made.

"I think there never was a faculty that was working harder than the Dartmouth faculty. There never was an alumni body that was working harder with the one spirit of desiring the best thing for the College than our alumni body. And the enthusiasm of the undergraduate is a fine thing. The students are honestly trying to meet the situation. Underneath all there lies the determination on the part of everyone to make his college life a service. We have the factors, therefore, which can make us absolutely secure of what Dartmouth will be in the future. Just as long as they make good, just so long are we going to have this demand from, others to come here. We must meet the demand and the problem will be solved, for there is today no opportunity for the advantageous use of funds superior to that presented by Dartmouth College."

Following President Hopkins' inspiring speech the presiding officer declared the meeting of the secretaries adjourned to the lobby of the Inn, where a further program was awaiting them. Coming out of the frosty night air which already registered ten below zero, the secretaries found a blazing fire of logs and the chairs arranged before a screen for the the display of stereopticon slides. Professor Bartlett was the speaker and he presented in his own delightful and informal manner scenes and incidents and characters of the old Hanover. The secretaries from the classes up to the middle 90's, and even later, saw many views thrown on the screen that have now gone and have become mere memo- ries and the faces of many a man who played his own part, prominent or even ludicrous, in the close-knit life of the College. Daniel Pratt, the great American traveler, the professor of dust and ashes, Ira Allen, Horace Frary, and many others lived again on the screen. It was in every way a talk of unusual interest.

Following Professor Bartlett, there was a careful explanation of the plan for the new memorial field, by Professor J. P. Richardson, faculty representative on the Athletic Council, and a statement by Graduate Manager Pender of the policies, past, present and. future, of the Council. Mr. Pender offered to answer any questions that might be asked him so far as he was able to, and for half an hour he told the secretaries the inside story of Dartmouth athletics. In the small hours of the morning this informal session broke up, on notice from Mr. Dana that they would gather again in the Faculty Room the next morning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMORNING SESSION

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleAFTERNOON SESSION

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleThe Harvard endowment excursion

April 1920 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1920 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Article

ArticleWYMAN TAVERN, THE INN AT KEENE, NEW HAMPSHIRE IN WHICH WAS HELD THE FIRST MEETING OF THE TRUSTEES OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1920 By Elgin A. Jones '74 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

April 1920

Article

-

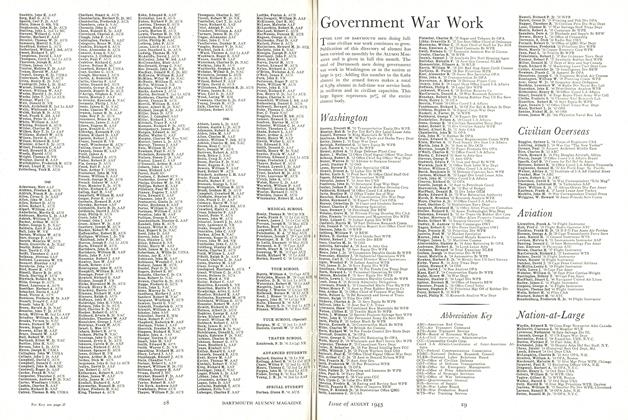

Article

ArticleNation-at-Large

August 1943 -

Article

ArticleCAMPUS CONFIDENTIAL

NovembeR | decembeR -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

October 1934 By Hap Hinman '10 -

Article

ArticleNotebook

Nov/Dec 2006 By JOE MEHLING '69 -

Article

ArticleCollege to Host Symposium

APRIL 1986 By L.T.H. -

Article

Article1915's Second President

December 1939 By LAWRENCE A. WHITNEY