is reported safely accomplished. The treasure ship is coming into port; and by way of celebration, Harvard salaries have already been boosted to levels that will seem almost beyond the stretch of academic imagination. If repressive measures may now be applied to Cambridge rents, and the oft-viewed, but ever magically withdrawing, peak of high prices may be actually achieved, scaled, charted and descended, the professorial lot at Harvard seems destined to enjoy considerable alleviation.

Meanwhile Yale has been giving its faculty situation a thorough overhauling to the end that the University is in quite as satisfactory a position as Harvard to smile successful beguilement over the fences of its neighbors. This cheerful condition is due in some measure to ever mounting endowments, but in larger degree to the annually recurring beneficence of the Yale Alumni Fund.

The fattening of Princeton's capital likewise goes on apace, while the eloquent appeals of Cornell appear to be setting in motion a sufficient supply of dollars to suggest the hope that beefsteak may once more adorn the academic feasts of Ithaca. All round it begins to look as if our temples of learning, large and small, might continue to keep their altar lamps adequately fuelized without material disturbance to the accepted scale of luxuries among the families of their neophytes.

This is most fortunate. To require parents to assume the full or even the major part of the financial burden involved in applying the benefits of higher education to their offspring would be a serious step. It might deal a mortal blow to those finer idealisms the cultivation of which constitutes the chief reason for being of our colleges. There is no stimulus to idealism like receiving something for nothing, or at least for less than it costs; whereas real prices tend to deflate the expanding soul.

And who would wish to quench the eleemosynary fervor with which Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Dartmouth, Amherst, Williams, Cornell,—and all the rest of the fine old endowed colleges—contribute to the support of family motor cars? The exact measure of this contribution would be difficult to determine, but some notion of it may be (gained at any great collegiate function that brings the parents and friends of college boys into the open together and enables them to display simultaneously their automotive opulence.

The purchase price of the cars at just one great intercollegiate game would make a respectable endowment fund for a university. Their upkeep cost for a year, if distributed as salaries among all the professors of New England, would cast those worthy gentlemen into an immediate delirium. A great fleet of aristocratic cars gives tone—especially to a football game. Some of this pleasing elegance might be diminished if the colleges were not endowed and hence—with accompanying prudence in the salary list—enabled to discount their tuition costs by fifty percent or more; fifty percent to the autogentility,—more to the proletariat.

It may be doubted—quite naturally—that endowments were originally intended to be applied directly or indirectly to the support of motor cars; or to the accumulation by undergraduates of marginal surpluses for use in following athletic teams and proving loyalty to them by large transfers of dollars staked not always with wisdom. In fact, it was not uncommon for early deeds of gift to have something to say about religion, learning and indigence. But so much of education now has so little to do with any of these things—except as the last is exemplified in the educators—that it is not strange that the minor aspects of endowment have been lost sight of in its general acceptance as the one and only, divine and omnipotent safeguard against financial ills and responsibilities.

In any event, the last resort of a college in distress is to increase its tuition fees. In the name of endowment, let them not be touched! It is legitimate to extract the last pathetic sou from the motheaten pocket of an ancient alumnus: it is legitimate to exploit every rank of college employee to the gray verge of hopelessness: it is not legitimate to require lusty, care free, and often spendthrift, youth to pay its way in full.

Willie Boodle and Marmaduke Millionbucks and Isidor Geltlwechsel may squander yearly allowances that would twice pay the house rent of all their instructors; they may direct the discounts of Alma Mater to the purchase of garlands for Tottie Coughdrops, but it would never do to eliminate those discounts. Such procedure would be undemocratic; and it would lead people to call dear old Bunkum a rich man's college: —and no institution of the higher brow can long endure that accusation.

Nevertheless a change in procedure is, soon or late, inevitable. Willie and Marmaduke and Isidor may or may not, subsequent to graduation, make such contribution to the world's intellectual and moral progress as to justify educating them at cut rates. The chance that they will eventually heavily reward their college for early favors extended is a remote one. It is to be remembered further that the great drives which are now in process are really to maintain the status quo. The millions that the universities have collected with such splendid toil are barely enough to keep these great institutions relatively level with their past; they offer little assurance of support for future growth. Nor is the anguish of these drives likely to seek early repetition.

The time is approaching when the income needs of the endowed colleges must be met by tuition charges at full cost to those who can afford to pay them. Endowments will then be held in reserve from which the poor man who is worth the trouble and expense may be so liberally assisted as to enable him to make fullest use of his cultural opportunities. When that time comes such competition as exists among the colleges will be based on quality of educational service rendered and not on the price charged for it.

The benefactions of generous friends and loyal alumni will still be needed to maintain and expand educational plants and to increase institutional capabilities for seeking and encouraging young men who have in them the germs of real power. Such benefactions will be given no less freely because 'to these obviously reasonable ends.

Wallace F. Robinson will be for all time enshrined in the kindly remembrance of Dartmouth undergraduates. In his gift of Robinson Hall for use as an official home for student activities other than athletic he did more for the undergraduate recognition of the value of these activities than could have been accomplished in any other way. With collegiate and intercollegiate , sports adequately officered, supervised, financed and housed; while journalism, literature and art endured merely a doorstep and gutter existence, the creation of an impression favorable to athletic things and derogatory to intellectual effort was inevitable. Mr. Robinson's recognition of the fact was immediate, his provision to counter it generously adequate. The constantly improved output of Dartmouth literary and artistic organizations bears witness to his foresight and wisdom. He provided the means for giving these organizations good standing in their own opinion and consequently in the opinion of others. He made prominence in them a desirable highroad to recognition. And, in offering a permanent place for the foregathering of men of common purpose, he ensured that gleeful interchange of ideas out of which grows successful co-operative effort. Mr. Robinson's first gift was of funds sufficient to build the hall which bears his name. Subsequently he provided an endowment fund to ensure its adequate maintenance and repair. Thus he made his monument complete. He himself had become a familiar and popular figure in Hanover. His presence at important College gatherings was a matter of course. His interest in all that concerned the College was unfailing. His death in February last is a source of very genuine sorrow,

The College welcomes the return of President Hopkins from an extensive trip among the alumni that has carried him as far west as the Pacific Coast. The journey has been in many respects notable. Not only have the gatherings of alumni been of record proportions, but the President has been called upon to address innumerable civic and commercial bodies.

Everywhere he has been received with enthusiasm. What he has had to say has made a profound impression. Besides binding more closely old ties of loyalty to Dartmouth, President Hopkins has carried into new fields the message of the College. Unfailingly he has left with those whom he encountered an increased respect for Dartmouth, and an enhanced conception of the breadth and vigor of its leadership.

Captain Morrill A. Gallagher whose sudden death in Portland was recently announced was one of those Dartmouth men universally known and loved by the alumni. He had that rarest and most engaging of qualities, a genius for loyalty. His college and his college friendships were the great things in his life. They absorbed almost all of his social interests; he gave himself to their service not only without reservation but with joy.

When the war came he was among the first to enlist. He went for the honor of his country, but the honor of Dartmouth was always in his thought. When .promoted to a Captaincy he found his satisfaction less in what it meant to him than in what it meant to others whose love and confidence he cherished.

The genius for loyalty carried Morrill Gallagher through many hard places, over many serious obstacles. It won him the tenacious devotion of his nearest circle of friends, the admiration and respect of those who knew him less intimately.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDINNER SESSION

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleMORNING SESSION

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleAFTERNOON SESSION

April 1920 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1920 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Article

ArticleWYMAN TAVERN, THE INN AT KEENE, NEW HAMPSHIRE IN WHICH WAS HELD THE FIRST MEETING OF THE TRUSTEES OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1920 By Elgin A. Jones '74 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

April 1920

Article

-

Article

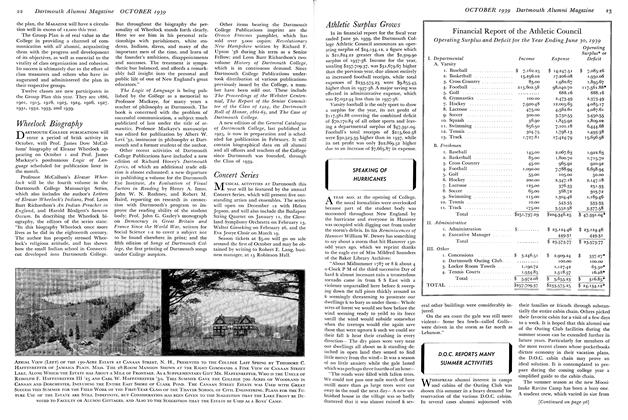

ArticleFinancial Report of the Athletic Council

October 1939 -

Article

ArticleFederal Music Chief

October 1940 -

Article

ArticleIn Brief . . .

OCTOBER 1970 -

Article

ArticleJean Passanante '75 forsakes greasepaint for director's chair

DECEMBER 1983 -

Article

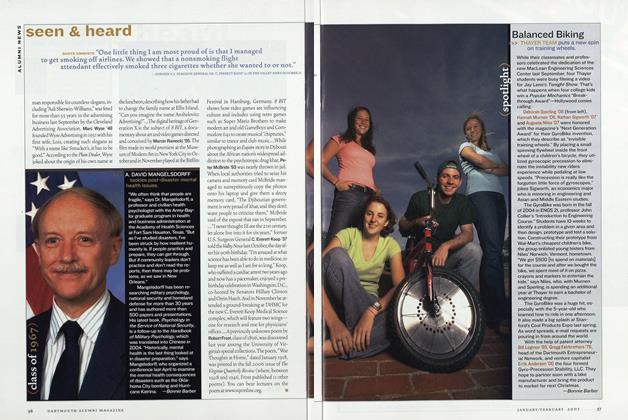

ArticleClass of 1967

Jan/Feb 2007 By Bonnie Barber -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1951 By PETE MARTIN '51