Ernest Fox Nichols for the presidency of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology will be of especial interest to Dartmouth men. The scientific attainments of Dr. Nichols are of such magnitude as to make him an appropriate intellectual leader for any institution primarily scientific in its character, as Technology is; and the fortunate condition of that' school in the possession of its new and splendid equipment should relieve the new president of that most -onerous and distasteful, of all practical duties, the constant seeking after funds wherewith to maintain the structure over which he presides. Since his withdrawal from administrative work at Dartmouth, where he served as president for seven years, Dr. Nichols has devoted himself exclusively to physical science, in which field his reputation is justly described as international. Administrative work in a scientific institution must naturally be more alluring to a scientist than similar tasks in connection with a purely academic, or mainly academic, college—such as Dr. Nichols had to assume when he served as the head of affairs at Hanover.

Speaking more broadly, interest may well be awakened also by the intimation of the newly elected president of M. I. T. that in his judgment that famous school has somewhat overstressed practical, or "applied," science to the exclusion of "pure" science; and that hereafter it would be well to have theory and practice go hand in hand. Dr. Nichols is himself an unusually eminent exponent of pure science and might therefore be depended upon to take this view of the problem. It is notable, however, that this very thing was among the incentives which led so practical a manufacturer as the late Gordon McKay to involve his bequest to Technology so intimately with Harvard as to preclude its being turned over to the more purely scientific school alone—he feeling, it was said, that not enough development of the inventive faculty was being produced by the Technology curriculum.

Incidentally there may be room for the query whether the cultural value of pure science, especially in the consideration of its historical development, has been duly appreciated by the non-scientific schools and colleges. The trend away from the classics and toward the so-called "practical" courses has based itself on something other than the cultural value of scientific subjects. Unless We.greatly mistake, the emphasis laid upon scientific courses in the academic institutions has been due to a wish to produce efficient engineers and experts with more speed, rather than to any expectation of broadening the general horizons of the mind. But it is notable that courses in the history of science are beginning to be offered in various educational institutions with the idea of affording a cultural background, instead of inculcating exact scientific learning. That this should be at least as enlightening intellectually as the familiar courses of the past in the history of philosophy seems a reasonable belief.

It is often difficult to know just where the cultural leaves off and the directly practical begins; but it seems to be the novel theory of Technology s incoming executive officer that, just as cultuial colleges need the leaven of practical studies, so also may technical schools stand in need of something which, while scientific, still savors of the academic.

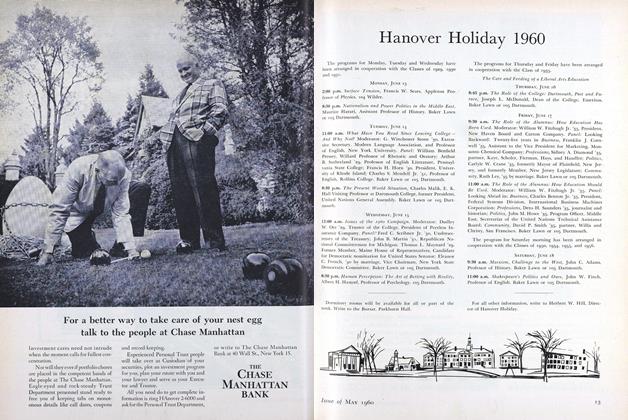

With the rapid advance of Spring comes the inevitable thought of another Dartmouth Commencement with its attendant train of class reunions. It is in some ways an inevitable disadvantage of our situation that such reunions entail a very considerable pilgrimage on the pal t of alumni; but the old drawbacks, which consisted chiefly in the difficulty of obtaining adequate accommodation, have so far been minimized as to leave it practically a mere matter of distance. Hanover is still a "fair greene country towne," such as formed the ideal of William Penn; but thanks to the growth of the college equipment it has become feasible to offer to returning classes rooms surpassing in convenience those which in older days were procurable under sundry village roofs by enterprising class secretaries, or by the -sons of older graduates who happened to be students at the time when father's fortieth anniversary drew nigh.

Even so, the tax upon the college facilities is heavy, since the size of the alumni body has increased in proportion with the growth of the physical plant. And it remains a thoroughly essential thing that those who intend to return, whether upon the stated occasions of a class reunion or in the intervals between such regular anniversaries, make timely announcement of the fact for the better prevention of disappointments. The College commonly clears out as much as it may of its regular resident population in order to make room in the dormitories for alumni visitors. In addition there is more room than of old, thanks to the development of motor communication, in such eligible hostelries as exist in Lebanon, Woodstock, Norwich, and even farther away from Hanover, which can be used by such as do not object to a daily motor pilgrimage of from seven to twenty miles. The comfort of such as come back for reunions, then, is vastly greater now than it was a generation ago. The satisfaction of such occasions, always great, remains constant.

Speaking as the representative publication of the alumni, the MAGAZINE would urge upon all its readers the desirability of the Commencement visitation, especially for such as are due for their regular class reunions. Nothing can take the place of such conventions of classmates, either as a means of retaining the class spirit or as the method of keeping alumni in touch with the college itself. "Better is the sight of the eyes than the wandering of the desire." Better by far is actual seeing than mere reading about what has been done at Hanover, what is now in process, and what is planned for the future.

The alumnus who has not visited the old town in, say, 15 or 20 years—and there are probably too many of whom this can be said—will be astounded when he does come, by the changes he will see. The old campus and its eastern row of buildings will be virtually the only objects to which one will require no formal introduction. It doesn't pay to let the college grow out of one's recollections to that extent. It is too much like leaving your parents when they are still young and not coming back until they are well along in the 80's—with this difference, that the older Dartmouth grows the more hale and sprightly she becomes.

Our great concern, voiced many times before, is to preserve the unity of the alumni body as a whole, which means precluding any feeling that, because of the lapse of years or because of long absence from the familiar scene, one is in a vague sense "out of it." The college belongs to us all and we belong to it.

There is also something about this recalling the classic fable of Antaeus, whom we vaguely recall as deriving fresh strength from his repeated contacts with Mother Earth. Every recurrent visit to Hanover makes one a more stalwart Dartmouth man. Fortunate are they who come back to all their class reunions—and thrice happy they who manage to come back every year.

Lectures to alumni, on the "Moore foundation" so-called,! the project for which was announced some years ago, are to be actually inaugurated this spring. The speakers selected for these first essays in. a novel field are Ralph Adams Cram, the preeminent ecclesiastical architect of the day, and Dean Roscoe Pound of the Harvard Law School. The names alone are a sufficient indication of an auspicious beginning, details of which will be published soon. Mr. Cram, aside from being the most notable American exponent of the application of Gothic art to the academic and religiousl structures of our time, is a many-sided essayist whose outgivings reveal a whole some horror of the mediocre. Dean Pound, primarily the leader in legal instruction at our most notable American law school, is among the most prominent advocates of a sane liberalism as the leaven for what has been passed on to us by inheritance in the way of intellectual attainment in general.

One especially appreciates the fitness of these selections as avoiding the easily besetting sin of "in-breeding", to which academic institutions are often prone the failure, due either to reluctance or to inability, to go afield and make intellectual acquaintances unconnected by tradition or association with the college itself.

The details are interesting. These lectures, each speaker giving eight, will be delivered at Hanover in the week immediately following Commencement, Tune 21. An incentive, therefore, will be afforded visiting alumni to stay on a few more days in . town—and with the shortening of the Commencement exercises this seems to us a very desirable thing, especially for such as have made extended journeys to reach the college for reunions.

The Moore foundation is, in its more extended title "The Dartmouth Alumni Lectureships on the Guernsey Center Moore Foundation" and represents a gift of $100,000 by Henry L. Moore of Minneapolis, a member of the board of trustees. The gift is a memorial to his; son, a member of the class of 1904, who died during his course at Hanover.

Recurring to the programme provided for the current year, Mr. Cram will direct his series of addresses to the consideration of "The Great Peace. Those who know Mr. Cram, or who have heard him speak on topics unconnected with' his profession, will not require to be told that these talks should be of most refreshing originality. Possibly they represent a project, of which we have heard him speak half in earnest, half in jest, which he once proposed to call "Twenty-seven Assaults on the Commonplace will have for his general subject "The Spirit of the Common Law." The essays of each will be divided according to the following sub-heads:—By Mr. Cram, A World at the Crossroads; A WorkingPhilosophy of Life; The Social Organism; The Industrial and Economic Problem; The Political Organization of Society; The Mission of Education andArt; Religion and Life; and The Personal Equation.

By Dean Pound: The Feudal Element; Puritanism and the Law; TheRights of Englishmen and the Rights ofMan; The Courts and the Crown; ThePhilosophy of Law in the NineteenthCentury; The Pioneer and the Law;Judicial Empiricism; and Legal Reasonand Justice.

An interesting addition to the series of "Dartmouth Reprints" has been made in the reproduction in a single pamphlet of two addresses to the student body at the opening of the college year—one by Dr. Tucker, as delivered in the autumn of 1908, the other by Dr. Hopkins almost exactly a dozen years later. What lends special interest to these two outgivings by Dartmouth presidents is the spread of human experience that lies between the occasions of their utterance, most notably the Great War, but only less so the unexpected and remarkable growth of the college,

The two selections were made because they are so typical in spirit and expression of the abiding ideals of Dartmouth. The address by Dr. Tucker was the last which he delivered as president of the college in active service—and it was given the title of "The Training of the Altruist." Dr. Hopkins's address was made at the opening of the present college year and took as its central idea the element of personal responsibility in the college.

When Dr. Tucker spoke, the New Dartmouth, although well under way, cannot be said to have given full indication of its surprising capacity for growth. The classes were notably larger than they had been a decade before—but they were still inconsiderable by contrast with the one welcomed by Dr. Hopkins in 1920. The war, with its amazing revelation of the overmastering powers of trained and instinctive altruism, had not come to give point, as it has since, to the general doctrines which Dr. Tucker then outlined. The sobering sense of great things yet to do, with the share which the colleges must take in the doing, is admirably set forth in Dr. Hopkins's much briefer utterance as a fitting sequel to the broad plan outlined by his great predecessor. But their real unity may be discovered in the emphasis which both speakers laid upon personal responsibility to the college, on the part of those who enroll themselves in its body of students. It is done, as it was bound to be, differently by each president, according to his bent—the one foretelling an ideal, the other making practical application of it after a great and unsettling world-crisis. In conjunction, the two form an admirably illustrative instance of the Dartmouth spirit as revealed by two sympathetic interpreters.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

May 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleANOTHER REPORT TO THE ALUMNI

May 1921 By DAVID LAMBUTH -

Article

ArticleCOMMUNICATIONS

May 1921 By H. W. ROBINSON -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

May 1921 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

May 1921 -

Article

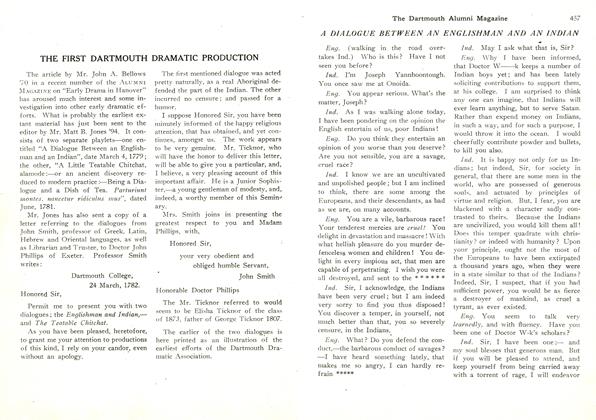

ArticleA DIALOGUE BETWEEN AN ENGLISHMAN AND AN INDIAN

May 1921