PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

May 1921 EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 May 1921

IV THE OLD CHAPEL

When .morning prayers took flight from the Old Chapel in Old Dartmouth Hall to the new and traditionless Rollins Chapel the College passed the dividing line between two phases. One of the many New Dartmouths began to displace an antiquated and, in many respects, pernicious old one.

The simple college of fifty years ago remains in the memory of many of us in vivid contrast with the huge complex, organism of today. The units themselves —educational, administrative, financial, athletic, artistic, social—are subdivided and of slow and unequal development. Comparison is valid; criticism is not fairly based on the standards of today.

My reference is to effects on the material of operation and production:—the undergraduates—without which the college would be futile; and especially to influences upon their disposition, manners, and customs, because these make the daily life of the college and largely determine the later graduate relations of the same men.

In the evolutionary process colleges in similar conditions have reached about the same stages, but if we looked the country over we should find much diversity in conditions and maturity of development.

I suppose that every college has its period, long or short, of mischief for mischief's sake. The monkey stage is never completely outgrown, but the' mischief incidental to some scheme or exciting occasion is quite different from that done without the occasion. Lawless collection of materials for a celebrating bonfire and heaping of all the gates in the middle of the Green, overthrowing some one's fence in a rush and painting a dignified statue red, resisting stupid or brutal police force and horning a professor, house-breaking for the sake of a trophy and changing the sign boards on the highway differ very much in the impulse that causes the one or the other. We shall always have the misdeeds of excitement; deliberate invention and perpetration of mischief have nearly died out from the more advanced colleges.

(The only serious instance we have with us at present is ringing in a false fire alarm, a misdemeanor so inconsiderate in trifling with a community's protection against great disaster that it can be done only by those without training for social life and of limited intelligence,)

In this respect a few years have made great changes. And the chief causes of the changes are obvious,—the spirit of the times; no longer is the perpetration of a malicious trick the object of admiration within or -without the college walls : the development of organized athletics; the husky lad aching for adventure is no longer compelled to steal the bell tongues or to steer a cow into a recitation room in order to demonstrate his prowess; in fact he is considered foolish and disloyal if he wastes his power in such a manner: different relations with the faculty; though no more kindly at heart, they have come down to a more companionable and comprehensible level: far better discipline, because less, and administered by experts, kindly, justly, reluctantly: and too many other interesting things in the busy life of the college.

As an important local factor, the Old Chapel, with its accumulated barbarities, disappeared from the daily life of the College in the autumn of 1885, though its influence lingered until as late as 1897, when senior rhetoricals were given up.

The room was shaped like a well-proportioned packing case. The interior might be described as wholly nave-ish. It was entered by two doors on the west. The entering multitude passed on the right and on the left a raised platform supporting a pulpit and seats for the faculty, and when the hustle was over found itself seated seniors and juniors in front, backed respectively by sophomores and freshmen. Opposite the platform, therefore at the east end of the room, was a low gallery for organ and choir. Galleries also ran along the sides, so high that their occupants, the Chandlers and Aggies could, if they wished, play cards or match pennies without observation. The seats were' long benches neatly grained and incised by the jackknives of many generations. There was no more beauty or grace in the room than in the bleachers now on the oval. It was cold in winter, and at times so .filled with smoke that the chorus of exaggerated coughs often obliterated the gospel. The atmosphere, fragrant with the prayers of good men, was also saturated with the microbes of deviltry. At this time and for many years after, the permanent members of the faculty took turns in officiating when for any reason the president was not there. This custom was well appreciated by the objects of prayer, and the attention to a novice's maiden effort was almost paralysing.

As the chapel and the church were the only assembly rooms in the village (though on a grand enough occasion seats were placed in the gymnasium) the proper, or at least the lawful, doings here would have fitted out a good variety show,—brilliant lectures, as of Dr. John Lord—how well I recall the high nasal, "O ! transcendental Carlyle!" and the clog dance which he apparently carried on back of the pulpit as his periods grew more and more dynamic—and senior rhetoricals; singing school and Daniel Pratt; college mass-meetings and projections with the calcium light.

The Chapel music was in charge of an organist and a chorister from the nearly defunct Handel Society. (Possibly some who read this may be induced to turn to Professor J. K. Lord's History and read there of this ancient and most honorable organization. It is a genuine loss to the College that one of the most notable and successful musical organizations in New England should have been allowed to lapse and should have been replaced later by the glee club only, with its jolly but trivial music. In the present awakening of the colleges to higher musical ambitions it might be possible to restore the name and purpose of the Handel Society, though it would hardly be possible to recover its early prestige.) At this time the society elected three or four members from each class, held occasional meetings, and was listed in the Aegis, but its only publicity was in the chapel service maintained "by the meagerly salaried chorister and organist. This relation to college affairs continued for many years with less and less discrimination in elections. The last stage was the election of a group of good bellows who could stand a 25-cents initiation fee, and a choral march to "Lige" Carter's where the 25 cents each was expended in peanuts and accessories. Along in the eighties the faculty appointed Professor Charles F. Richardson and the writer a committee to strive for its reanimation. But there was no life in it. Ancient reputation could make no stand against modern conditions. The difficulty about discarding good old things is to know which are finished forever and which will be required again.

My memory is a little hazy, but I think that in our freshman fall ('68) the organ was a melodeon with the heaves, and a "used" organ was installed during the year. This organ was a mark for all the kinds of pranks that could be performed with or upon an organ, the most effective being to wedge open a high squealy pipe so that, when the air was turned in, a continuous and pervasive wail came forth until the air was gone. It was indeed "an ungodly kist of whistles." Organists of cunning learned to give the organ a cautious trial in advance, and many mornings the choir sang without any organ because it had been misguided into freakish ways. The chorister had his trials too; he was paid to have a choir there, but no choir was paid to be there. At least one faithful chorister, deserted by his choir, carried through the whole hymn alone, much to his credit and to the joy of the audience. It was always a demonstrative audience and surprisingly sensitive to any little misadventure in the music.

We, the commoners, as contrasted with the dwindling aristocracy of the Handel Society, had no hymn books in those days, and our only helpful contribution to the service was a sort of humming obligato when the tune was familiar. It may be that earlier the "Compleat Psalmist" brought up from the Indian school at Lebanon, Ct., or "Watts and Select" was in the students' hands. History does not tell. It might have occurred to some one that the animals' attention could have been engaged at least temporarily by letting them roar. The little Aegis is moved to put forth an editorial' on the subject, in the spring of 1871, which concludes, "We ask not now a modern chapel; we ask not voluntary attendance; we ask not to have it warmed in winter; we ask not even easy seats; we do ask hymn-books. Give, O give us hymn-books."

Among the pleasant customs of the place was that of noticing, "featuring," -celebrities, that is to say college notorieties. The students faced the doors of entrance and as men came in who by reason of some action (not meritorious) were in the public eye, although they might be unaware of it, they were greeted by well-graduated "wooding up," sometimes gentle and significant, sometimes tempestuous and dust-raising, always undesired. One morning during the suspense period of a faculty investigation involving a considerable number of men, the hymn accidentally selected for the day had for a refrain "Lord, here am I, send me; send me," which was received with joyful appreciation.

Here Daniel Pratt, the Great American Traveler, delivered those famous lectures of which I remember only the titles, "The Inventive, Invisible ' Propelling Power of all Valuables," and "The Vocabulary Laboratory." Daniel was that for which the people have invented so many synonymous terms,—he was cracked, nutty; he had a partial vacuum under his hat; or in real elegant language, he was troubled with flittermice in the campanile. I do not know whether any one ever had the curiosity to trace him to a relation with the rest of the world. He appeared. He lectured. He gathered the cash. He made off. And that is all we knew of him. Fie was a primitive form of the modern smoke-talker. Under guard and escort of a self-chosen committee he was brought to the chapel stage where he was received with thunderous applause. After a serio-grotesque introduction he started on his "lecture" which was a swirl of incoherent verbiage. It soon wearied an audience little inured at that time to lectures, and the senior president would interrupt with the suggestion that it would be wise to take up the collection before the audience began to fade away. After the collection Daniel was nominated President of the United States with applause comparable only to that of a national "convention. Then it was whispered that the faculty were on the way and that he would better beat it. Beat it he did, sometimes with the speed of a jack rabbit, followed by a hooting howling mob. The last time that I knew of his presence he made the statement before he left that "the bottom of hell had fallen out and hell had lit in Hanover," which certainly was not incoherent. But the boys were not so bad. He got a pretty good purse; and on one of the more agitating occasions, when Daniel dropped the collection which had been bagged in a handkerchief, the mob fell to and gathered and returned it all.

By ancient cus- tom, still continued, the senior class closed their work in the College with the "Sing Out,"— "Come let us anew Our journey pursue," to the tune of Amesbury. It was as difficult to carry through without some slip then as it is now; but the occasion was a solemn one, notwithstanding, it meant so much to men who were emerging from the shelttered and directed life to the struggle in an unknown world. Knowledge of the time when this custom originated seems now to be lost. My father, who entered college in 1832, said that it was considered an old custom in his day.

On Wednesday afternoon, seniorsone to four, as many as could be dragged to the sacrifice—spoke original pieces to the assembled college. It was an exercise in favor with no one, and the assembled multitude was like a' pack of wolves, watching for any weakness in order to pounce and devour. Woe to the senior who had made himself disliked! Woe to the platitudinous bore! Woe to the halting forgetter of lines ! As a typical ordeal for public speakers it was most commendable and if generally applied would have saved the world eons of dreary deliverances. For the man who had something to say and said it quickly and audibly could have a hearing, and who else deserves one? In fact, any one who could hold that crowd for twelve minutes could preach a sermon in a boiler factory to an intoxicated gang of cannibals who knew no English. Although it lacked decorum as a college exercise it dragged on long after the chapel was abandoned for religious uses, but was finally discontinued as too demoralizing to the College and too exhausting to the presiding officer.

The chapel was a convenient exchange for the products of the "Darkmouth" Press—class recriminations, , grinds, protests against some utterance of the Dartmouth, or the Aegis, or some faculty action—and casual leaflets were often to be found scattered over the seats. It was, of course, the duty of the janitor to intercept or to collect all such literature, but he was only one and not a college graduate at that, and the name of his adversaries was Legion. After I had been on the faculty a year or two a variation of this custom aroused my interest and my curiosity, which had to wait some thirty years for satisfaction. When the College was all assembled, the bell had ceased ringing, and the President had risen to conduct the service, suddenly a huge sheet of paper loosened itself from the wall back of the faculty, gently opened and unrolled displaying a bitter attack upon one of the classes present by another. For a period great noise prevailed, but after it ceased the service went on. It was especially trying for the President, as he was compelled to go through the service without any knowledge of the attraction behind him.. The ingenious inventor told me all about it many years after he had secured an irrevocable diploma.

From time to time other objects were discovered in the chapel which were not in harmony with devotional serenity,—a skeleton from the Medical School, a real donkey, an anticipatory cradle.

Among the methods employed by consecutive classes to show distaste for one another was that known as "greasing the seats,"—smearing the benches with some viscid non-volatile substance which disqualified them for their proper use; molasses or soft soap would answer the purpose very well though rather too easily removable with water. I do not know that any one was ever beguiled into sitting down in the mess, and it is difficult to understand now why this form of affront was taken so seriously, since it gave the victims freedom from chapel until the seats were purified. The typical case, of course, was treatment of the freshman seats, but one morning the Juniors—my own class—were thus evicted from their devotions. Outrage unspeakable! An idiot with initiative always has followers. He—that unknown idiot— yelled, "Over into the Sophomore seats,"' and. the whole class trailed after him like so many particularly foolish sheep. What could be more absurd? Why should Juniors ever wish to revert to the haunts of Sophomores; and especially when they could go out and sit on the grass and lose one chapel? This business called for blood, and men were already coming to grips for a row which would have been memorable in the history of the College when suddenly a presence appeared among them. It happened that chapel that morning was in charge of a lovable gentleman with a keen eye and unquestioned reserve force. "Stop", he thundered; and they stopped. "Go out," he ordered the invaders ; and they went— past the ranks of seniors who stood on their seats and jeered. I do not know whether any other member of the faculty could have brought off this harmless conclusion, but "Charley" Young, later known to Princeton students as "Twinkle" did, and of course we liked him all the better.

On occasions frequent enough to establish a custom the Seniors and Juniors, entitled to precedence, remained in their seats at the close of the brief services while the lower classes rushed past them. The whisper had gone around that a cane in Freshman hands challenged the Sophomores to die for the right just outside the front doors. But it had been tried before and usually the Voice of Authority walked off with the cane. Only the injudicious really grieved ; for there were great inconveniences in unprepared clothes and unsecured text books.

One more custom which I will mention was firmly fastened on the Old Chapel,—the college mass-meetings. I have always supposed that they were unauthorized. In any case when business was to be transacted in convention of the whole college, the president of the senior class called a mass-meeting commonly by notices passed around during the services, and, as much as possible, men were prevented from, going out at their conclusion. All classes had recitations immediately after chapel, and the meetings used up a large part and frequently the whole of the recitation hour. I can imagine the annoyance to the members of the faculty as they sat waiting for their classes to appear. From the student standpoint this was regarded as an ancient right. It lasted many years after this time, but before the chapel was abandoned I think permission to hold such a meeting was required, and granted only for substantial reasons.

It would be an exaggeration to claim that the matters here mentioned were of daily occurrence, but I think it is a modrate statement that at this period no student could go through college without an experience of them all. And they meant much more in the life of the college than the bare incident.

When in the fall of 1885 the regular chapel services were transferred to the new chapel, the well-planned gift of Edward Ashton Rollins of the class of 1851, a huge load of hindering customs and precedents was taken out of the way automatically, without discussion or question, and the forward movement of the College quickened and lightened.

The Corpus Delicti

THE SEATS OF THE MIGHTY

THE REGION OF HARMONIOUS STRAINS

The Great American Traveler

The Wily Faculty Man

FROM THE SOPHOMORE POINT OF VIEW (President Smith forbade rushes between '71 and '72)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleANOTHER REPORT TO THE ALUMNI

May 1921 By DAVID LAMBUTH -

Article

ArticleThe announcement of the choice of Dr.

May 1921 -

Article

ArticleCOMMUNICATIONS

May 1921 By H. W. ROBINSON -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

May 1921 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

May 1921 -

Article

ArticleA DIALOGUE BETWEEN AN ENGLISHMAN AND AN INDIAN

May 1921

EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72

-

Article

ArticleATHLETIC SPORTS AT DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1905 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleUNDERGRADUATE AFFAIRS

January 1915 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

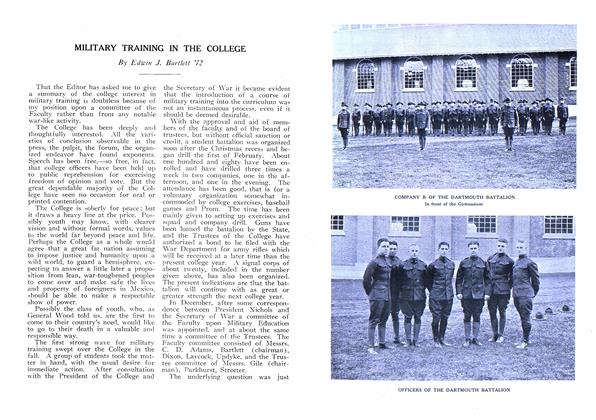

ArticleMILITARY TRAINING IN THE COLLEGE

June 1916 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

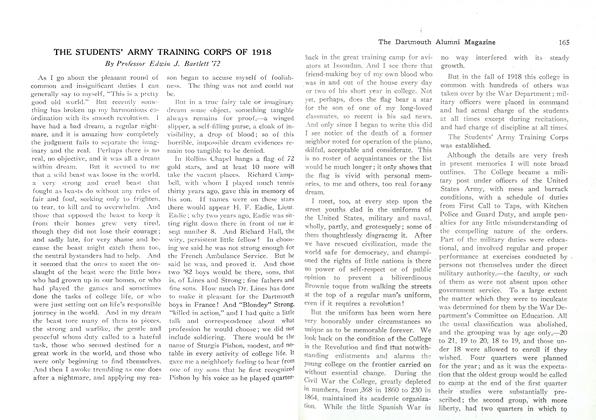

ArticleTHE STUDENTS' ARMY TRAINING CORPS OF 1918

February 1919 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE REJOINDER OF JOAN

August, 1923 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

February 1920 -

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB CIRCULAR STIRS EDITORIAL PENS

March, 1922 -

Article

ArticleWebster and Choate Were Medical Students

APRIL 1929 -

Article

ArticleCrossing the Green

September 1986 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal

June 1934 By Leonard D. White '14, Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticleTHE CITE UNIVERSTAIRE AND THE LATIN QUARTER

MAY, 1928 By Shirley G. Patterson