As I go about the pleasant round of common and insignificant duties I can generally say to myself, "This is a pretty good old world." But recently something has broken up my harmonious coordination with its smooth revolution. I have had a bad dream, a regular nightmare, and it is amazing how completely the judgment fails to separate the imaginary and the real. Perhaps there is no real, no objective, and it was all a dream within dream. But it seemed to me that a wild beast was loose in the world, a very strong and cruel beast that fought as beasts do without any rules of fair and foul, seeking only to frighten, to tear, to kill and to overwhelm. And those that opposed the beast to keep it from their homes grew very tired, though they did not lose their courage ; and sadly late, for very shame and because the beast might catch them too, the neutral bystanders had to help. And it seemed that the ones to meet the onslaught of the beast were the little boys who had grown up in our homes, or who had played the games and sometimes done the tasks of college life, or who were just setting out on life's responsible journey in the world. And in my dream the beast tore many of them to pieces, the strong and warlike, the gentle and peaceful whom duty called to a hateful task, those who seemed destined for a great work in the world, and those who were only beginning to find themselves. And then I awoke trembling as one does after a nightmare, and applying my reason began to accuse myself of foolishness. The thing was not and could not be.

But in a true fairy tale or imaginary dream some object, something tangible always remains for proof,—a winged slipper, a self-filling purse, a cloak of invisibility, a drop of blood; so of this horrible, impossible dream evidences remain too tangible to be denied.

In Rollins Chapel hangs a flag of 72 gold stars, and at least 10 more will take the vacant places. Richard Campbell, with whom I played much tennis thirty years ago, gave this in memory of his son. If names were on these stars there would appear H. F. Eadie, Lieut. Eadie; why two years ago, Eadie was sitting right down there in front of me in seat number 8. And Richard Hall, the wiry, persistent little fellow ! In choosing we said he was not strong enough for the French Ambulance Service. But he said he was, and proved it. And those two '82 boys would be there, sons, that is, of Lines and Strong; fine fathers and fine sons. How much Dr. Lines has done to make it pleasant for the Dartmouth boys in France! And "Blondey" Strong, "killed in action," and I had quite a little talk and correspondence about what profession he would choose; we did not include soldiering. There would be the name of Sturgis Pishon, modest, and notable in every activity of college life. It gave me a neighborly feeling to hear from one of my sons that he first recognized Pishon by his voice as he played quarterback in the great training camp for aviators at Issoudun. And I see there that friend-making boy of my own blood who was in and out of the house every day or two of his short year in college. Not yet, perhaps, does the flag bear a star for the son of one of my long-loved classmates, so recent is his sad news. And only since I began to write this did I see notice of the death of a former neighbor noted for operation of the piano, skilful, acceptable and considerate. This, is no roster of acquaintances or the list would be much longer; it only shows that the flag is vivid with personal memories, to me and others, too real for any dream.

I meet, too;, at every step upon the street youths clad in the uniforms of the United States, military and naval, wholly, partly, and grotesquely; some of them thoughtlessly disgracing it. After we have rescued civilization, made the world safe for democracy, and championed the rights of little nations is there no power of self-respect or of public opinion to prevent a biliverdinous Brownie toque from walking the streets at the top of a regular man's uniform, even if it requires a revolution!

But the uniform has been worn here very honorably under circumstances so unique as to be memorable forever. We look back on the condition of the College in the Revolution and find that notwithstanding enlistments and alarms the young college on the frontier carried on without essential change. During the Civil War the College, greatly depleted in numbers, from .368 in 1860 to 230 in 1864, maintained its academic organization. While the little Spanish War in no way interfered with its steady growth.

But in the fall of 1918 this college in common with hundreds of others was taken over by the War Department; military officers were placed in command and had actual charge of the students at all times except during recitations, and had charge of discipline at all times.

The Students' Army Training Corps was established.

Although the details are very fresh in present memories I will note broad outlines. The College became a military post under officers of the United States Army, with mess and barrack conditions, with a schedule of duties from First Call to Taps, with Kitchen Police and Guard Duty, and ample penalties for any little misunderstanding of the compelling nature of the orders. Part of the military duties were educational, and involved regular and proper performance at exercises conducted by persons not themselves under the direct military authority,—the faculty, or such of them as were not absent upon other government service. To a large extent the matter which they were to inculcate was determined for them by the War Department's Committee on Education. All the usual classification was abolished, and the grouping was by age only,—20 to 21, 19 to 20, 18 to 19, and those under 18 were allowed to enroll if they wished. Four quarters were planned for the year; and as it was the expectation that the oldest group would be called to camp at the end of the first quarter their studies were substantially prescribed ; the second group, with more liberty, had two quarters in which to cover the required work, and therefore some option in other studies; and so on. The courses recommended were simple and "practical," that is they tended to make serviceable men. Two unusual composite courses were laid out and given with large measure of success, "Sanitation and Hygiene," and ' War Issues." Military Law was another course outside of the usual college curriculum. A special feature was an intensive course in Chemistry designed for two years and spoken of as the Chemical Warfare Course." Students in this course (except beginners) and in Medicine and Engineering were released from part of the drill and allowed to give their whole time to their professional work. This was a novelty in chemical instruction here, and, especially in the case of students who had been qualified for advanced work, gave admirable results. There were supervised study hours in Chandler and Tuck Halls, and plenty of military drill.

From many colleges have come mut terings—more than mutterings, growlings and moanings of discontent; and also, it is said, from the War Department. The electric atmosphere of war soured the academic milk. The coarse and arbitrary men of blood failed altogether to appreciate" the essential delicate poise when philosophy is at the helm. How can teachers teach if their pupils (otherwise absolutely regular, by the way) are held out of the class for K. P.! On the other hand, "Inter armasilent leges." When a big fight is on there isn't much use in talking about the way we generally do it. What is the use of letting this talk stuff stand in the way of making officers when hurry is the word? So said some and made their actions correspond.

Undoubtedly there have been all degrees of success in carrying out the short experiment.

If one recorder were able to gather up, and chose to set forth in a carping manner, all the administrative errors for which no one at the College was responsible it would make an instructive history of illusory information, conflicting commands, missing supplies, and general muddling. The influenza, at its worst just before the initiation of the S. A. T. C., was partly due to lack of foresight, but chiefly to conditions inseparable from crowding men together.

But we can claim, and challenge anyone to disprove it, that nowhere was success greater than in Dartmouth College, and the reasons are creditable to all concerned. If the same conditions prevailed elsewhere no doubt the success was as great. First of all the administration made no panic-stricken grab for numbers to be maintained at the Government expense, and lowered its standard of admission not a bit. Then the students accepted the military discipline cheerfully if not lovingly. If men whom they knew so well could endure the hardships and dangers of the battle front, they surely could stand the inconvenient novelties at home which were making them ready to swell or to replace the hundreds already in active service. The faculty appointed a Committee on Military Relations and turned the whole management over to them in hearty and patriotic cooperation with the purposes of the Government. While from time to time there was very proper inquiry, and enough protest to remedy troubles that only awaited attention for relief, the whole spirit was of unswerving loyalty. Doubtless some found it a queer and lonely world in its ultra-modernity, but they bore up bravely in faith that the Golden Age would return. But while the students and faculty did well their parts, a predominating factor was the reasonable and considerate attitude of the commanding officer, Major Patterson, and his aid, Lieutenant Pickett. There were, of course, small misunderstandings and mild frictions inevitable in the organization of an unprecedented system involving some 800 men with whose names and scholastic duties it was necessary for the officers to become familiar, and who in many cases were as jocular with military discipline as a pup with a ball of yarn. But the frictions were never intentional, and wherever possible were promptly and courteously remedied as soon as attention was called to them. When the full difficulty of their task is appreciated both officers and students of the College will acknowledge a debt of gratitude to the army officers for performing their duties in so careful and kindly a manner.

Considered with reference to a future very uncertain at the time, this was a hard but necessary device to carry on a Prolonged war. The smoothly flowing current of a great college was wholly turned into new channels in order to deliver power at the utmost speed. It had the advantage of being set in a quiet and undemonstrative New England village whose men and women were fixed in a determination as cold and hard as their granite. Not a personal call was unheeded. Not a sacrifice of habit or comfort was grudged. Not a call for funds came that was not over-subscribed. And the student body, with earnestness and unquenchable humor, fitted well with the setting and relieved its tendency to grimness more than a little.

But as we may look at it now it was an episode and not a revolution, too brief to make permanent changes; almost too brief to justify inferences. Already we are back in the old ways without visible profit from the military decomposition of academic customs and precedents. It might have been well to throw the whole bunch of tricks into the scrap heap even if we went to it and picked out the good ones for the new collection. At any rate we are on the sunny side of the cloud and may find in its lining occasion for joy. If not joyful it was surprising to discover what the military power of the United States could bring about. Actually it got every man out of bed at 6.15 in the morning and put him back at 10.15 at night. It emptied every fraternity house not only of its lodgers but of its social loungers; it ran a college without a "required" cut or any other kind of cut. They were all there or accounted for every time. In a village where it is. necessary to maintain unsightly wire fences to prevent the destruction of beautiful greensward, and where the College sends out a corps of lancers as chiffoniers to spike and gather the scraps into baskets the spectacle of a hundred men in uniform gathering with their fingers every cigarette butt and bit of paper visible to the naked eye was wholesome and edifying. There are superficial objections to continuing this practice in times of peace but are there fundamental ones ? Would not parents and guardians give their approval? The supervised study hall was unpopular for several sound reasons, but even here a rude and uncultivated form of fun was introduced by the extravagant custom of snapping pennies at the non-commissioned officers in charge who evidently had not learned that in the back of the room is the pedagogue's strategic position of vantage. In all seriousness why could not the college profit by this device, stripped of its undesirable trimmings; not for the many, of course. But in every college, for a time, there is a group of spineless, effortless loafers, neither brainless nor vicious. They are too useless to retain, with too many possibilities to lose without regret; when they have exhausted administrative patience why not give them a choice between departure and regular supervised hours of study for a semester? Wanderers on the street at hours when their schedule showed that they should have been somewhere under cover were picked up or reported by the P. G. or M. P. or whatever part of the alphabet it was, to the joy of all their peers. And only with glee were the stories circulated of how A. B. was saucy to the face of his non-com with an emergency word and was promptly marched to what stood for a guardhouse, and how C. D., mistaking a potato for a projectile practiced with it a ballistic curve in the dining room with the sequel of peeling similar tubers all the following day. And there were no sea lawyers to make much headway against the frightful injustice of extra drill or curtailed liberty for a whole company when some culprit in it could not be discovered. Yes, it was funny.

But how fast they learned their military duties, and what a fine appearance they made towards the last in review or at retreat! Though it must be confessed that the firm belief that within a year many of them would be dead and many more crippled choked one up a bit, so I am told. Will the influence of that fine ceremony of honor to the flag that symbolizes so much that makes life worth living continue to the end of their lives, I wonder. Unquestionably the civilian spectators who ignored their own obligations of respect received very useful lessons. Years ago on a festival occasion Bissell Hall, the old gymnasium, was used as an auditorium, and the platform for the speakers was decorated with flags so placed that the various orators of the occasion took their stand upon one of them, until to the just humiliation of all the careless accomplices in this outrage, one of the speakers, a veteran of the Civil War, declared that he had fought for the Union and that he would make no speech with his feet on the old flag. To be sure he was a little impolitic, but that did not blunt the point of his protest. That incident, at least, could not happen now.

There will be much difference of opinion as to the result of this undertaking, which can only be regarded as an incomplete experiment. It has shown that under stress the organization of the college—this college—can be rapidly and completely put at the disposal of the Government, and that military regulations are not incompatible with a fair scholastic return; for from the scholarly point of view the work of the fall has been far from a failure. In some cases it has been better than usual. And there is Certainly no reason for disregarding it and beginning over, as we hear some are doing. It has shown that the faculty can quickly plan new and in a sense alien courses, adapt existing ones, and turn their own teaching skill and experience into ways previously untried. It has shown that students, happily never long oppressed with unnatural seriousness, can enter into the spirit of a great enterprise and endure with only superficial grumbling conditions very irksome in comparison with their previous experiences. It has not, however, established new habits and customs, and it is at least doubtful what permanent impression it has left. It is certain that after the declaration of the armistice on November 11 the interest in military affairs rapidly and perceptibly flagged.

The experiment does not give basis for permanent military training in the college, unless it should be part of a scheme of universal training in which the college man would receive credit for work well done in the college, or be sent to a training camp. Military drill, nonfaicical, rigid, exact, would be a most admirable element in college life, provided, that all military control could stop with the drill • but to hope for both conditions at the same time is as reasonable as to expect omnipotence to furnish two mountains without a valley between, or to move from one point to another without passing through the intervening space, The fact is, as demonstrated in many colleges in previous times of peace, that military training worth anything, with its stern requirements and definite penalties is quite incompatible with the present easy going ways of the college. And whether it would be better to check initiative and student "activities," reduce social life, insist on a well-ordered daily schedule, a democratic equality of living conditions, and unquestioning obedience in all things is another large question.

We may now be very thankful that the Students Army Training Corps existed as it did, and that it and its necessity have, for the present, ceased.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMILITARY NEWS

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleThe annual dinners of Dartmouth

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ROLL OF HONOR

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH REUNION IN PARIS

February 1919 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1916

February 1919 By Richard Parkhurst -

Books

Books"Psychology and the Days Work"

February 1919 By CHARLES FREDERICK ECHTERBECKER

Edwin J. Bartlett '72

-

Article

ArticleATHLETIC SPORTS AT DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1905 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

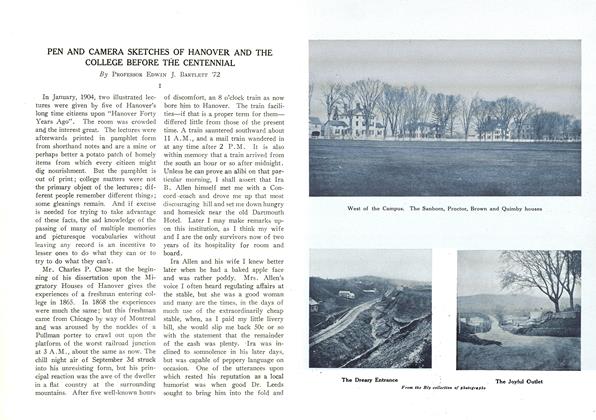

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

December 1920 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

May 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE REJOINDER OF JOAN

August, 1923 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleMATERIES MEDICI

June 1924 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72

Edwin J. Bartlett '72

-

Article

ArticleATHLETIC SPORTS AT DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1905 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

December 1920 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticlePEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES OF HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE BEFORE THE CENTENNIAL

April 1921 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72