of Alumni Secretaries, has once more met in Hanover and demonstrated anew its usefulness, not only to the college, but also to the various classes represented. It is almost alone through the secretary that a class maintains its vital connection with the college proper- or the college proper its vital connection with the alumni in these class groups. It is the "secretariat"—to borrow a Wilsonian word—which affords the essential connecting link.

From the most resent meeting one gathers this central truth—that the post of a class secretary is one which should never be filled by any man who is not fully aware of the serious need of doing the job both well and thoroughly. It takes all sorts of people to make a world, but only one sort ever makes a good secretary for a class of graduates. Unremitting industry and unfailing interest are the prime essentials. Failing these qualities in its official representative, a growing indifference of the class to the affairs both of itself and of the college is too probable.

Yet the chief responsibility, after all, must rest with the class in the end. The unresponsive member, who never answers his secretary's urgent appeals for information about himself, is a menace. Such are at their minimum strength in a good class and at their maximum in a poor one. The best secretary that ever lived can be broken down and made into the least effectual by a preponderance of indifferent classmates, unwilling to second even by the inconsiderable amount of effort required of them the onerous duties of the one man who is trying to keep them together, to retain their mutual interest, and to make them, through himself, an integral part of the Dartmouth fellowship.

To impress the secretaries with the seriousness and importance of their job is easy and is done afresh every year by the gathering at Hanover. To get at the widely scattered men whom these secretaries represent is difficult, and it affords the chief problem of the secretaries themselves.

How frequently should classes be called upon by their secretaries to make written reports of their individual activities? Ought it to be done only just previous to the quinquennial reunions? Ought it to be done annually? Or ought one to split the difference and gather in the reports from individual class-members only twice in the five years between the reunions? Is the requirement one which can be standardized? Is it even desirable to enforce on the classes some standard constitution and fixed system of rotation in office? Or is it best to have permanent class officers, holding by a life tenure such positions as president, secretary and treasurer?

Questions such as these naturally agitated the recent secretaries' meeting and always will agitate such gatherings. The material for debate is virtually unlimited. Classes can be cited which afford splendid examples of well-knit class spirit from among those addicted to highly different practices. The present writer's, class, with an unusually good record for holding firmly together, never changes its officers but has today the same organization that it started with something like 27 years ago. Others, equally efficient, change every five years. Each would probably regret an enforced change as making for abandonment of its approved customs. Perhaps, then, the best answer is that of the pragmatist, in favor of any system which in practice is found to yield satisfactory results.

This has been an age in which standardization has flourished, all the way from Ford cars to fabricated ships. It has not proved an unmixed blessing. The very fact that it takes all sorts of people to make a world precludes the application of standardized systems to people with that assurance which might attend a similar application to materials. We should view the project for a standard class constitution with some apprehension, despite the theoretical arguments which seem so nearly unanswerable in favor of the plan; and especially do we regard with suspicion the project to make the "secretariat" of a class change frequently, since we must feel that this would be found a detriment more often than it would work a benefit. The secretary who has been long on the job knows his men, knows their habitats and habits, has his records well enough in hand to keep them familiarly. Changing once in five years may mean getting a new man but not surely a better man for the work—but certainly one who is unfamiliar with his duties and who will acquire that familiarity only at about the period when it is time for him to lay them down and break in a new official. A comprehensive working knowledge of one's class—especially a large class—is not acquired by one new to the work. Once acquired, it is an asset not lightly to be forfeited merely to get in another set of officers. The relief to a well-worn secretary would be great, we may all admit. What one fears is a net loss to the classes and to the college.

The secretary of a class is the custodian of a trust. That trust entails upon him a hard and often a thankless labor —utterly unremunerated, yet demanding a large amount of time and labor if the work is to be done as it should be done. No one ought ever to undertake it without the fullest recognition of its obligations. It may be a life job—and unless we greatly mistake it has been such with the best secretaries in the long history of our Dartmouth alumni bodies. It may be that all the questions cited at the outset of this article can best be answered by the various classes for themselves, according to what has been proved to be most convenient for them. If so, the standardized class constitution cannot go very far beyond fixing the general list of officers and leaving it to the classes, as before, to work out their own salvation as to rotation, class funds, reports and such like incidentals. As in other forms of politics, "Whate'er is best administered is best." .And the thing which proves to be best administered in one class will very probably turn out to be worst administered when applied to another. One never can tell.

Professor C. D. Adams outlined at the dinner of the secretaries association and trustees, held recently in Hanover, the projected alterations in the college curriculum, whereby it is hoped to promote a better-rounded liberal education in Dartmouth by confining the elective system chiefly to the junior and senior years. It appears to be felt that a too great latitude has been permitted hitherto, especially in the first two years of the college course; and further that there is not always a benefit in the common system of "majoring" in the choice of electives, especially if what one has in mind as the ideal of college education the attainment of a reasonably liberal culture. Professor Adams wisely admitted the impossibility of "knowing everything about something and something about everything," preferring to qualify this glib overstatement in more practical ways.

The proposition, then, is to make the work of the freshman and sophomore years mainly required work, leading toward either the A. B. or B. S. degree, freedom to elect along certain specified lines being postponed until the student has attained this required groundwork of a liberal education.

As is quite usual in human experience, the original innovation of the elective system led in nearly all the colleges to a harmful excess, which was only partially corrected by the device of compelling the electives to follow a certain specialized direction usually referred to as "major" subject. There soon developed instances in which an artful student could, by proper ingenuity, attain his degree by electing in succession a variety of elementary courses devoid of much difficulty, and. thus present the required number of hours without any danger of breaking down through overstudy. The evils of the various correctives to this practice now appear to be the promotion of a one-sided development; and therefore a further corrective is suggested in the return to required work in the first two years.

If every student were aware by his junior year of the probable line which his life work would take, no doubt an elective system designed to prepare him for that work could be better defended. The man who intended to become a lawyer would "major" in subjects allied to that profession, and so on. With this there are several sore troubles—one of which is that the immature junior usually doesn't know what he is going to do for a living when he gets out, and another that if he devotes his college course to a definite major specialization he forfeits something of that broad liberal culture which the A.B. degree at least ought to imply in its possessor. It is palpably essential, in order to give a reasonable coherence to an elective system, that a too free hand be not permitted in the choice of subjects of study, even after one enters the glorious estate of the junior class—that best of all one s college years. It is desirable not to "major" too vigorously or exclusively in one line. In cutting down the opportunities to elect at large by making the first two years a period of required work, we believe the college is on the right path, with every probability of attaining a workable compromise between too little and too much freedom in choosing the lines of one's erudition.

"Omnibus ad quos hae literae pervenerint, salutem in Domino!"—or did that cherished sheepskin say, "Omnibus has litteras perlecturis?" In either case the issurance of diplomas in the Latin tongue has lately been under the harrow of criticism as a practice no longer defensible in an age devoted to matter-of-fact efficiency. At least one speaker in the gathering of Dartmouth secretaries bemoaned the adherence to Latin, especially when it descends to the attempt to Latinize a familiar proper name as "Josiam Jones," on the ground of manifest absurdity.

And yet—well, the Magazine makes no secret of the fact that it retains a weakness for this survival of an ancient grace. It would perhaps answer every practical purpose if the parchments distributed by the Praeses et Socii stated quite simply, "The president and trustees of Dartmouth College hereby certify that Josiah Tones is admitted to the degree of Bachelor of Arts" and let it go at that. It might even be efficient to do away with parchments and merely issue bits of printed paper, to be neatly detached from a pasted block and filled in with a fountain pen—like orders for a set of books to be paid for in instalments. But it seems on the whole better not to do it that way.

There is a mouth-filling sonority about those rolling Latin sentences—and to claim that almost no possessor of a degree is capable of translating them is, or certainly ought to be, a slander. If a man who pays five dollars to obtain his A.B. degree cannot understand the rather sad Latin in which it is couched, he doesn't seriously deserve to be called an A.B. There is more to be said for the scientific men, perhaps—but even there let us retain a sweet savor of academic antiquity. It does no good, perhaps—but it likewise does no harm. Even those alleged abominations due to our effort to translate English names into the classic tongue—"Dartmuthensis," "Nov. Hant. in America," and the like—are dear to us. Is it not sometimes the source of illumination? One who finds New Jersey chastely referred to in the classic speech as Nova Cæsarea may actually acquire unexpected knowledge of his derivations! Thomas Proudie, bishop of Barchester, was wont to sign himself, sacerdotally, "Thomas Barnum"—"Barnum," if you please, being the contraction of Baronum Castrum, whence Barchester! One who, standing under Peter's dome, sees flaming before his eyes the majestic prayer of Our Savior"- Pater Noster, qui es in Coelo, sanctificetur nomen tuum"—will not esteem that prayer the less the next time he utters it in more familiar English.

One may not often see one's diploma. Most of us put them away in neat tin canisters and forget where they are. Nevertheless they are our title, deeds; and the thing they stand for ought to command a certain stateliness of formality with which a bit of Latin mystery sorts full well. Let us be slow to abandon the traditional formulae.

Considering that many men, by no fault of their own, are compelled to sever their connection with the college before completing the prescribed course which justifies the grant of a' degree, it is manifestly desirable to eradicate as far as it is practicable so to do the invidious distinction between graduate and non-graduate. Of course this eradication is possible only to a limited extent. One who hasn't graduated simply hasn't graduated, and cannot with justice be held entitled to a degree as if he had graduated. It is already possible, if need arises, for such to obtain a certificate from the college, setting forth the.facts as to his term of residence and scholastic attainments. But there is evidently a well defined feeling that apart from such technical details it should be possible, and would be eminently proper, for the alumni body to ignore mere failure to pursue the course to its end when it comes to treating the non-graduate as a member of the Dartmouth fellowship in ordinary matters of alumni contact.

Probably every class now extant has members who are valued associates, and most enthusiastic and loyal as well, who were compelled by adverse circumstances to cut short the college course, but who have never wavered in allegiance to the institution—and who cherish their class associations quite as warmly as any who did graduate. Probably, also, the classes themselves usually in time forget the fact that such an associate did not finish his course and would even be skeptical if reminded of the fact. It is desirable, certainly, that such men be made to feel similarly welcome and at home in all gatherings of the alumni body, where the test is at bottom enthusiastic loyalty to Dartmouth. The passport in that case is not a Latin parchment. Wherefore it is pleasant to learn that among the votes taken by the assembled secretaries at Hanover was one recognizing the status of the non-graduate as entitling men to cordial recognition in all alumni gatherings where no question of degrees is involved, but where the Dartmouth spirit reigns alone and supreme:

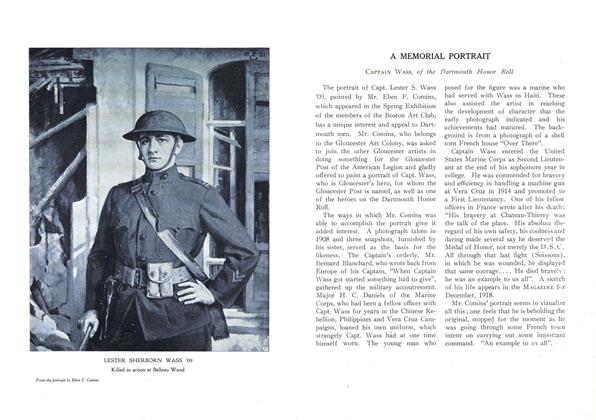

It may be that only a few, perchance no one else, on the Dartmouth Roll of Honor will have the good fortune to be visualized for the years to come as Mr. Comins has visualized Captain Wass in the portrait reproduced in this issue. Yet each one on that Roll will be memorialized in Dartmouth's new Memorial Field. The men on that list gave their youth. Their gift of youth will be approximated by a gift for youth. The great new recreational and intercollegiate playfield will provide the facilities for a college of two thousand, which "The Oval" did for a college of three hundred. Embodying in its enlarged area not only the spot where they played, but also the spot where they drilled and dug trenches in training for the World War, the new playfield will gather up and appropriately hand down their memory to the oncoming Dartmouth generations. The alumni by classes and individually and the parents and friends of the men on the Roll are making this possible. On May 19th the subscriptions amounted to $133,072.25. Commencement should see the subscriptions well along toward the required goal. Each gift by an alumnus is a return gift of continued serviceability, which will carry on into the Dartmouth of the future the spirit of service which, here speaking from the fine canvass of Mr. Comins, is exemplified in the life and death of every man on the Honor Roll of Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue