If Hanover ever becomes an airport, the attention ofstudents will be turned more than ever to the art of flying.But the fact remains that flying is attracting more and moremen from college ranks, as the recently published decisionof two prominent students at Dartmouth to enter aviationindicates, and it is to outline the seriousness of the business, and to give some idea of the conditions which confront the would-be airman that the Alumni Magazine hasasked Lieut. Studley of the Navy to write something of theopportunities of Dartmouth men in this new field.

HANOVER AN AIRPORT

I HAVE always thought I would like to fly up to Hanover. As I recall it, there were a number of places where a landing could be made. Of course my eye at that time was not accustomed to judge fields from this point of view. But there must still be a number in the vicinity big enough and smooth enough for a landing.

Or a seaplane would do as well. The old swimming beach would be an ideal place to run up on. Then a few stakes well driven in and lines to the float and the wing tips, and you could leave the ship there as long as you wanted.

But I have never had the chance. My sea duty has all been on the West Coast, and my three years of shore duty were spent down in Florida, at the Naval Air Station at Pensacola. We could get planes for week-end trips there. But Hanover was a little too far away to make in that time.

I have wondered though whether Dartmouth is taking any interest in this new aviation. For these last three years have unquestionably marked the beginning of a new period in aeronautical history. Before that only the army and navy and the air mail were operating on a firmly established basis. Now the output of commercial planes greatly exceeds those for the government. Transport operations and private flying are overshadowing our doings.

I can think of various things that could be done with a plane at Hanover. For those who are practically minded, distances in terms of hours will be interesting. At comfortable cruising speed, Boston can be made in an hour and forty-five minutes. New York is three hours away. An hour's ride would take you into Caada. And any one who lived in the East could fly home for an occasional week-end. For a young man whose pocketbook would stand the strain, the cruising radius of a plane is a point to be considered.

And the season of the year is immaterial. A cabin plane can be kept comfortably warm by exhaust heat, while skis will enable a landing to be made nicely on snow.

Of course the Outing Club comes naturally to mind. Flying clubs are being formed all over the country. A good plane can be purchased for as little as $3000, and when bought by a group, the cost to the individual is not great. Nor is maintenance, if the plane is cared for by members, unduly expensive. A flying club would be a natural subsidiary of the Outing Club.

As an outdoor sport, aviation ranks up at the top. There is a zest to it that is found nowhere else. You give her the gun and the engine responds with a staccato roar. The plane trembles and vibrates as the ground rushes past beneath you, faster and faster. But the vibration quickly vanishes as the wheels lift clear, and the ground drops away. Here in the air the plane rides easily, smoother than any car on any road. It responds instantly to the lightest touch. A crook of your finger will raise the nose to climb, or bank the wings for a turn. Then, when you get enough altitude, you can put it through its paces and feel it respond with the verve of a spirited horse. It will swing you in the tight circle of a flipper turn, wing pointing at the ground, wheeling so sharply that you hit your own slip-stream. It will rear and plunge through a split-S, or surge up and oyer in a loop. You can flutter lazily downward in a falling leaf. Or, if you know your plane well enough, you will find a kind of smooth beauty in a sensitively executed wingover. And when you come down, there is soulsatisfying accuracy in a precision landing.

A NEW VIEW OF HANOVER

To those who like to see the earth from high places, a plane gives new independence. New Hampshire, with its hills and mountains, must be a beautiful country to fly over. You could easily circumnavigate it in five hours. Mount Washington is less than an hour from Hanover. Lake Sunapee is a mere twenty-minute jump. One could see more of the state in an afternoon than in a week of travel by more ordinary means.

For the amateur photographer, a new field is opened up. Aerial cameras have been perfected until they can be used with a high degree of precision. Beautiful panoramic views can be captured on the films. In a few hours of flying a large scale aerial map of the College could be made.

Exploration of the White Mountains by air would be easily practicable. There is a fascination in flying over mountainous country. You see it in a new perspective. Sailing smoothly over ridges and rivers and forests, circling arOund peaks, gliding through valleys, there comes a new sense of freedom. You have a wider scope, a greater range. You can match magnificent distances with a speed that conquers them lightly. The earth spreads itself out beneath you. A whole mountain range lies within your vision.

And there are wonderful light effects to be seen from the air. I shall always remember one day off the southe rn California coast. The ship was to fire a torpedo practice, and we were circling over her waiting to chase the torpedoes. It was late afternoon, and clear. Snow caps on peaks a hundred miles away were visible. The still air was silky. The sea was a flat green-gray mirror. Between us and the sun was a great bank of gray clouds, silvered around its edges with light. Through a rift the rays of the sun fell on the cliffs of Catalina Island, five miles away. Rising sheer from the water, the bare rock shone with an orange hue, woven in lights and shades. Every ridge stood out in sharp relief. Soft shading marked every valley. The jagged roughness of its rocks was smoothed by distance till its contours were rolls of warm velvet. It lay like a stately ship at anchor, a burnished silhouette cut from the calm sea.

The New Hampshire hills would be beautiful at sunset. At five thousand feet on a clear day you could see fifty miles. As the sun dipped, lights and shadows would play over peaks and valleys. Here a ridge would stand out in clear-cut outline. There in a valley would be approaching dusk. Hues would change and mingle. The nearer green of woods and pastures would shade into the blue of more distant hills, while the colors of the sky would be reflected from outcroppings of rock. It would be a picture at which to gaze.

BUT FIRST lOC MUST LEARN

That is one side of the story. But before any one lets his enthusiasm carry him away, there is another side to think about.

If you want to fly, you had better be a good pilot. The consequences of being a dub are too unpleasant.

That is where flying differs from other things. You can take a couple of lessons in golf and then spend a year on the links working up through the dub stage. If you try that in aviation, you are likely to wake up some day in the hospital and learn that the junkman is offering ten dollars for your plane. The man who wants to take flight training should know exactly what he is doing before he starts in.

Learning to fly is not an easy matter. That is a fact which must be faced by the man who is thinking about it. Skill in handling a plane cannot be picked up in a few weeks time. There is no comparison with driving a car. In the air twenty things must be learned for every one on the road. And the possible penalties for mistakes are not to be taken lightly. Flight training can be given without risk. But it is safe only when scientifically directed.

The first thing to be considered is therefore where to take training.

The school which guarantees to make you a competent pilot in ten hours is a good one to stay away from. They may not be intentionally misleading. But they obviously do not understand the principles of flight training. It is graduates of such schools who keep the casualty lists filled up.

An adequate course of training includes ten hours of dual instruction and at least thirty hours of solo flying interspersed with instruction flights at five-hour intervals. I will not go into the details of instruction here, as I have covered those exhaustively elsewhere. But I want to emphasize the fact that there is no short cut in learning to fly. No economy is more obviously false than that of cutting short a flight school course. The extra expense is appreciable. But it is nothing compared to the possible cost, not only in money but in terms of life and limb, of trying to fly with inadequate training. Department of Commerce statistics indicate failure of the pilot as the cause of fifty per cent of accidents. But I do not agree with them. My own estimate is ninety per cent.

For instance, engine failure is listed as a cause of a large proportion of crashes. But engine failure is not an excuse for a serious accident. A careful pilot will always be able to make a safe landing with a dead motor—provided he knows how to do it. But he cannot wait until the engine actually stops and then expect to learn it. Unless he has been properly trained by an experienced instructor, there is a good chance that he will lose control.

PILOTS MUST BE CAREFUL

In 1926 I was checking a student at Pensacola. A number of times I closed the throttle to similate a forced landing, requiring him to pick an emergency field and shoot it. Each time I had to take the stick to keep out of a spin. I sent him back to his instructor for additional work on forced landings. After completion of this I checked him again and found him satisfactory. The following week, on a solo cross-country flight, his engine actually stopped. He shot a small field and came to a stop with nothing worse than a wing slightly torn by a post.

A small piece of advice may not be amiss here. An elementary solo student who tries to do the things he sees instructors do can get himself into plenty of trouble. One student at Pensacola admired the way his instructor spiraled in toward the seaplane beach and landed just off the hangars, where he could taxi right in. He tried it himself one day. But unfortunately his landing was not so good as the instructor's. The plane rebounded from the water and he had to give her the gun. He pulled her back and climbed as steeply as possible. But a church steeple just beyond the hangars was a little too tall. It picked him out of the air and deposited him, much embarrassed, in the churchyard.

One other thing to note. The student who listens to everything he is told will learn a large number of facts about flying which are not so. But on the other hand when a thing comes from an authoritative source, it is a good idea to believe it. Some of us were watching students at the landplane field at Pensacola one day. The motor of a plane stopped at 200 feet altitude just after it had taken off. Now the manual says, "In case of engine failure on a take-off, put the plane into a glide straight ahead." The student apparently did not think the book meant what it said. The ground ahead was covered with low scrub and small trees which would have torn up the wing fabric to some extent, so he tried to turn back to the field. Unfortunately at a low altitude this cannot be done, as a large number of pilots have conclusively demonstrated. We watched him turn in a flat spiral, fully realizing what was going to happen. At about fifty feet he ran out of flying speed. The plane fell off into a spin and crashed. He was not seriously hurt, but the plane, instead of being brought in with slightly damaged wings, was a complete washout.

ROMANTIC IDEAS WON'T WORK

The only way to learn to fly is to take a complete course in a scientifically organized school. And any romantic fancies about the thrill of flying had better be left on the ground. Training is plain hard work. It means constant plugging away at elementary maneuvers until they can be executed with unfailing precision. The student who thinks the air a place for care-free, joyous abandon is apt to wake up in a tail spin.

Incidentally, the maintenance of a plane requires a skilled mechanic and rigger. It must be in perfect condition every time it goes into the air. Once you get up there you cannot stop to fix anything. A man who intends to take care of his own plane must know as much about maintenance as he does about operation.

A flying field is no place for an amateur. Or rather, the amateur must be as good as the professional, since the law of gravity applies to private planes as impartially as to transports. No one can carry passengers in interstate commerce until he has qualified for a Department of Commerce transport pilot's license. A man who thinks his own safety worth working for will as soon as possible meet the same standards.

So, if any one feels the desire to see New Hampshire from the air, this is the way to go at it.

But if I first tried to prevent undue enthusiasm, neither do I now want to be discouraging. Learning to fly is not easy, but neither is it exceptionally difficult. Like everything else, a man must have a certain natural aptitude for it. But if he has that, he can become a competent pilot by putting the necessary time and effort into his training.

GOVERNMENT TRAINING BEST

Adequate and safe training is still unquestionably expensive. Comparatively few men can afford to pay for it. Probably the best opportunity for a college graduate is in the reserve forces, either army or navy. Both train students who, on qualification, are given commissions as reserve Second Lieutenants or Ensigns.

The Navy selects a certain number of college graduates each year who are given preliminary training at air stations in the various naval districts. Those who are successful can then go to the Naval Air Station at Pensacola for an advanced course, which was recently established there. They also take a thorough ground school course in structure and rigging, aviation engines, theory of flight, meteorology and aerial navigation. And there is practical training in aerial gunnery and bombing.

Fairly high standards are maintained, and not all students qualify for solo. Only those are selected who show evidence of ability to become capable pilots from the point of view of naval requirements. An appreciable proportion are turned back when they come up for solo checks. But if a man can meet the requirements he can get considerable solo time.

On completion of the course, the student receives a commission as a reserve ensign. For the last two years, fifty reserve officers have been given a year's active duty for advanced training. I had one young officer with me on the New Mexico last year. I found that he was, for the experience he had had, a very fair pilot. So I kept him busy on the hack work we have to do- towing sleeves for the anti-aircraft battery, piloting for radio tests, taking the mechanics up for pay hops and various other odd jobs. He later qualified on the catapult, and I was able to send him up several times during tactical maneuvers at sea. This flying netted him twenty to thirty hours during some months. When he finished his active duty, he had nearly enough time for a transport pilot's license.

Active duty in the Army or Navy reserves offers probably the best opportunity for training that is open to the college man today. He is assured of proper instruction, and has the opportunity to fly various types of planes. He associates with experienced pilots and learns something about practical operations. And not only is there no expense involved, but during his commissioned service he gets good pay.

For a man who wants to take up aviation as a career, this is unquestionably the best way to get into it. There are at present not enough qualified pilots to fill the demand. Commercial organizations are anxious to get service trained men, as they find them better trained and more competent. Any one with a Naval Aviator's certificate is sure of finding a job.

The growth of great air transport companies seems assured. Expansions and consolidations of existing companies haye been frequently reported in press despatches. The future operating executives of these companies will naturally be men who have flown the airways themselves. With a license once taken, the first rung of the ladder is in the pilot's cockpit of a transport plane. A single-engined one at first. But perhaps a year later a big tri-motored ship. It is here, with responsibility on his shoulders, that a man really learns the game. Here he acquires the practical experience which alone will give him a sound foundation in operating aviation. And here he piles up the first thousand hours, the minimum time required to qualify as, to use the journalistic phrase, a "veteran pilot." He needs at least that time before he is fully competent to fill an executive job.

If there are any Dartmouth men who are looking toward aviation as a career, I believe this is the best way to start. First, training in the Army or Navy. Second, if you can get it, a year's active duty. Third the pilot's cockpit of a transport plane. Finally, whatever job your ability will take you up to. Or, if you can do it, an airline of your own.

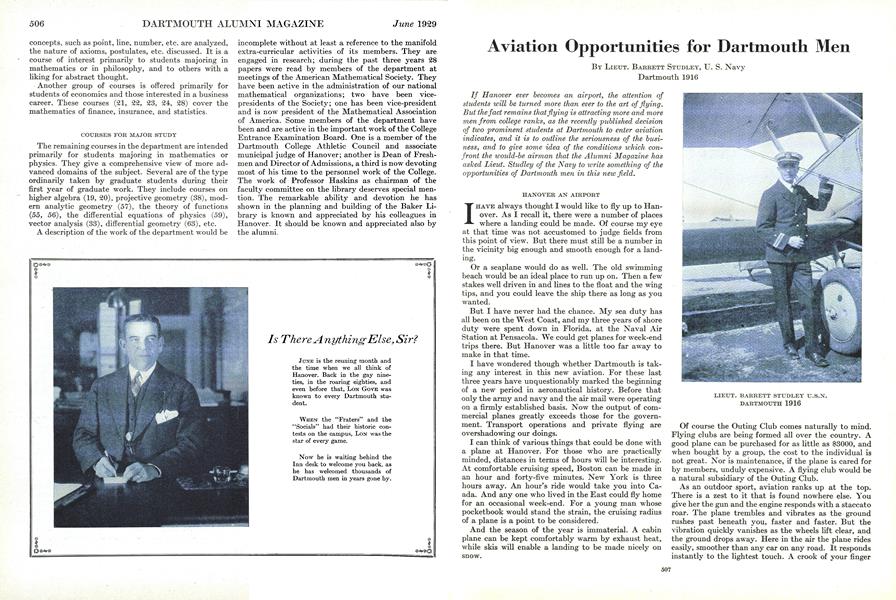

LIEUT. BARRETT STUDLET U.S.N. DARTMOUTH 1916

ENTEKING A LOOP

"N. T. 1 IN FLIGHT" LIEUT. BARRETT STUDLEY U.S.N. (DARTMOUTH 1916) PILOTING

A SPLIT-S TURN. FALLING OFF

BASEBALL IN THE 90's The colors were green and white in those days, thus the banded caps.

Dartmouth 1916

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Faces in the Windows

June 1929 By Clifford Hayes Smith '79 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1923

June 1929 By Truman T.Metzel -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1929 -

Article

ArticleA Visit to Hanover

June 1929 By E.W.Field -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1898

June 1929 By H.Philip Patey -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1918

June 1929 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

Article

-

Article

ArticleBEQUEST TO THE COLLEGE

December 1918 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY CONSENT TO FRESHMAN PICTURE

April, 1922 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

JANUARY 1971 -

Article

ArticleJOHN LEDYARD AND HIS RUSSIAN JOURNAL

MARCH, 1927 By James D. McCallum -

Article

Article1900*

May 1939 By LEON B. RICHARDSON -

Article

ArticleWhat a Change!

November 1945 By P. S. M.