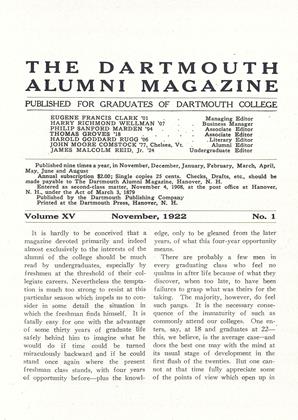

and indeed almost exclusively to the interests of the alumni of the college should be much read by undergraduates, especially by freshmen at the threshold of their collegiate careers. Nevertheless the temptation is much too strong to resist at this particular season which impels us to consider in some detail the situation in which the freshman finds himself. It is fatally easy for one with the advantage of some thirty years of graduate life safely behind him to imagine what he would do if time could be turned miraculously backward and if he could stand once again where the present freshman class stands, with four years of opportunity before—plus the knowledge, only to be gleaned from the later years, of what this four-year opportunity means.

There are probably a few men in every graduating class who feel no qualms in after life because of what they discover, when too late, to have been failures to grasp what was theirs for the taking. The majority, however, do feel such pangs. It is the necessary consequence of the immaturity of such as commonly attend our colleges. One enters, say, at 18 and graduates at 22— this, we believe, is the average case—and does the best one may with the mind at its usual stage of development in the first flush of the twenties. But one cannot at that time fully appreciate some of the points of view which open up in the roaring forties. The year's at the spring, and all the world is young. One is "on one's own," perhaps for the first time, and there's a zest in this freedom. To expect the sobriety and balance of forty in the college lad of 18 is too large an order. It is left for those of us who are three decades out of college to tell ourselves how differently we should do things now if we were just beginning. It is for those just entering upon their college course to repeat the same general errors that we committed some thirty or thirty-five years before. Why quarrel with it? And yet....

Does any freshman fully realize what he is facing? There is an element of awe in new surroundings and unfamiliar associates. There is the business of settling into the new environment, which takes time. But after that—say after the first month, or at the farthest the first semester—one is shaken down, settled, acclimated. One is at last part of the college and free to look around. It is a fascinating place, with manifold activities only too well calculated to overlay and obscure the main object of college attendance, which is education. One has one's duties and one performs them well enough, if wise, to escape the judgment. But this is precisely what one is certain to regret in later years. It's the doing things only just well enough, the contentment with what was once charitably called "a gentleman's mark," the too remote consciousness of the opportunity's general magnitude, that one regrets when one comes to the forty year. "We should get so much more out of it if we went to college now !" What a pity we were not such wise old men at the moment of our matriculation!

Possibly there should be ' a sort of baccalaureate sermon for the matriculants. The opportunity would be most inspiriting. If one could but find the right word to say to those who otherwise must fail to' see all that is at hand until it is far past—even as you and we! If only one could be told how dearly the world esteems scholarship, how fleeting the present chances will come to seem, how bitter the regrets of such as waste the golden time and then sigh in vain for another chance—as most of us candidly admit is true of ourselves! If only the pomps and vanities of the passing show could be sensed at their true, and all too meagre, worth—the acclaim of athletes, the coveted class distinctions, the various things that turn to ashes in the hand so soon! Not that one would utterly deny the virtues of all the attendant alloys which mingle with the finer metal—for they have their place. Only it seems so soon to be so unimportant a place, compared with what it seemed while it was our personal concern ! No one fully grasps that until it is too late to do him any good. It is rather like what Chimmie Fadden (a personage celebrated a quarter-century ago) remarked of the opinions of women: "You never know what a woman's goin' to think till it don't do you no good to know."

The colleges exist primarily to educate. Fathers send their sons to college primarily to be educated. They are not so inhuman as to wish them to have no fun in the process; but they reasonably ask, and the college reasonably asks, that the recipients of this favor take as much as an ordinary young person reasonably may of the chief thing offered at this table. No one is going to regret the failure to take it more poignantly than those who at the moment neglect it. The thing is to make them see it, while there is time. Perception is easy enough after the whole thing is over and one has the advantage of perspective. At close hands we "cannot see the wood for the trees", as the saying is. Probably nine-tenths of every class will agree, after some score of years, that they wasted too much time on that which was not bread.

One recognizes quite cheerfully that by no means all the educational value of a college course lies in text-books and lectures. One only insists that more value lies in those things than most of us appreciate at the time; and one argues only for a keener estimate of its worth. It may be possible to exaggerate it—but it is extremely difficult to do so and the danger in any individual student's case is remote in the extreme. The instances in which students break down from overstudy are amazingly few. The instances in which the regretful graduate curses his undergraduate indifference to his chances are deplorably many. The only time to correct the situation is while one is on the ground.

It is a difficult task to draw the judicious line between greasy-grinding and not grinding enough; indeed it is a task very commonly beyond the powers of a youth set free from the oversights of home, given a pocketful of money, and told to go to it. If there is any miracle, it lies in the fact that we get as much out of our college lives as we do. The point is that most of us wake up to wish we had got more, and to tell ourselves that if we had it all to do over again we should get more. Moreover it is harder now than ever it was when we older alumni were students. There is so much more in the way of distractions, so much more in the way of side-issues, athletic, social, or other, which have an educational worth of their own but which are terribly susceptible to the process of overdoing. The time to be devoted to education remains as it was. The opportunities to dissipate it are multiplied to no end. Decidedly, then, a sermon to matriculants is indicated—with the uncomfortable feeling that it will have about as much affect on young ears now as it would have had in our own time.

Meantime, however, there come strong evidences that the world outside the academic cloister is changing its tone toward some of the collegiate things once held in undue reverence by over-enthusiastic alumni. The day when a great corporation sought as its recruits young men whose sole claim to distinction was making a 70-yard run down the field to a touchdown has evidently passed. More than one successful business man has been heard to affirm that he should regard a Phi Beta Kappa key more highly as evidence of worth in an applicant than a whole shelf of silver trophies, or a dozen medals. It was not ever thus. One can remember the time when captains of industry cheerfully found jobs for the gladiators of their alma mater, on the quaint assumption that a world's record in the hurdles, or a reputation for carrying the ball forward between guard and tackle necessarily meant talent for some business in which the brain played a part superior to the brawn. Something has happened to change all that. It is possibly too much to say that an athletic record is a positive disqualification today for a young man emerging from college and looking for a job; but at least it may be said to be no great recommendation and in many quarters it is frankly regarded as prejudicial - something to be rebutted by clear evidence that this idol of the Sunday supplements and sporting pages has real brains, as well as a stalwart body . and abounding grit.

There's a reason for this, and it is not far to seek. The business world merely discovered that an athletic record didn't really mean much beyond a record for athletics—and athletics has a very remote part in selling bonds, or writing insurance, or assisting in the management of any industrial business, or in trying cases in court.

To get anywhere today a young man has got to know something and has got to be able to use his head even more adroitly than he uses his arms and legs. By much celebrating the corpore sano part of that famous Latin tag, men had momentarily lost sight of the mens sana. It is the latter which is now emphasized the more. And all the time, of course, the important thing is to have both. It is not amiss, surely, to bring to the attention of undergraduates full early in their career that the famous few, so glibly and familiarly celebrated by the sporting editors of the land during the fleeting period of their effulgence, are not so eagerly sought for that reason alone when it comes to landing a job.

Beware the pseudo-fame of college days ! It has its worth—but nothing in the world is more easily exaggerated beyond its merit. The star athlete, who is a star athlete and naught else, will have four years of glory and fifty or sixty of oblivion. The crowded hour of glorious life may seem worth the price of an age without a name—but it isn't. In these days, the star athlete must be rather more than of fair average scholarship to pass muster with acute business men; and the star athlete who is perpetually on probation might as well not apply at all. There is no place for him.

Possibly the most frequent omission which one hears older graduates regret is that of general reading. It is an age in which every one reads for relaxation —to be entertained. There is abundant opportunity to while away ah idle hour in reading trash and men too easily acquire the habit of preferring trash to better things. No man can claim to be decently cultured who is unfamiliar with certain well established classics of our own tongue—in which one must infallibly include the King James version of the Bible, along with a host of literary works by secular masters. This, which is true of all men, is particularly true of such as aspire to the "learned professions", so-called, or who plan to do any writing. There is never going to be a chance to make up the reading which is not done while in college. There's never going to be so much leisure for it again. There will never in later life be so good a chance to obtain guidance from competent advisers as to what to read, nor will good books ever again be more ready to hand. Some things must be read in youth if they are to be read at all. Which brings us once again to a favorite point of insistence—to wit, that the next great task of Dartmouth college .must be to provide adequately for its library and attendant activities, too long suffered to mark time in surroundings sadly outgrown.

What has been said already, although written before the delivery of President Hopkins's introductory address to the students, makes it but little necessary to comment at length on that address, which embodies much the same general idea and amplifies it in a way which the MAGAZINE most heartily approves. The president's remarks seem to us the most stimulating and suggestive utterance of the year in educational circles; and their central thought is that those only should seek collegiate education who are willing to make at least a reasonable use of their opportunity.

Dr. Hopkins invited, quite deliberately, a general discussion by the selection of a single picturesque phrase, probably well aware that it would be miscbnceived by hasty critics, but employing it because it is practically the only formula which will embody his general idea in a brief form. "There is an aristocracy of brains" is an assertion which challenges the reader at once and which is perfectly certain to set some, who fail to take the meaning of it, in a ferment of protest. There is no occasion for that, of course, and the comment of press and public so far as it has come to our notice generally approves both the form and the matter so boldly and tersely expressed. Nothing more genuinely democratic was ever said of college education. .

'"Aristocracy" has been so long abused as a term that it has come to have a snobbish sound, quite foreign to the plea advanced in this welcoming speech to the Dartmouth undergraduates. The president was careful to append an explanatory context. This is no snobbish "aristocracy of brains." It has no exclusive canons of birth, breeding, wealth, or social position. It is open to any man who will lay hold of his privileges, and it is "made up of men intellectually alert and intellectually eager, to whom increasingly the opportunities of higher education ought to be restricted if democracy is to become a quality product." That we believe to be absolutely true. The directness and brevity with which the president puts his thought shames much that has been written above by us around and about the same general idea.

"Too many men are going to college" was another telling phrase. This also is true, although unquestionably it is intended to be read in the light of understanding. Too many men are going to college who ought not to be there; and too few are going to college who ought to be afforded the opportunity—kept out by the intrusion of those who are not really seeking education, but only a mixture of social prestige, athletic distinction and personal pleasure. The ultimate ideal is to weed out the latter before they get started and give the chances to those who will use them.

All this does not imply a perversion of the established college tradition, or convert Dartmouth into an institution seeking only the extreme perfection of a few ripe scholars. We understand its aim to be what it has been for so many years since Dr. Tucker first began his inspiring leadership—to wit, the education of just as many young men as can possibly be accommodated for the leavening of the entire citizenship. But it is demanded that this multitude be after education and willing to make that the primal aim of their residence in Hanover. No others need apply—and those who do apply will be winnowed and sifted with the hope of confining college privileges to those who esteem them enough to use them. The college does not demand the impossible. It does not even demand the exceptional. It demands the reasonable amount of devotion to intellectual effort and it proposes not to tolerate drones in the hive, whose one idea in college is to squeeze through somehow with a minimum of concern for the intellectual side of their academic existence. Men who have to be coaxed, cajoled, baited, or driven into a reluctant recognition of the educational element of their careers would be better displaced by others. Too many such are going to college—a drag on their fellows and an insuperable obstacle to those who remain outside while desiring to come in.

Observation of the product of our colleges inclines us to believe that the president's admonition comes at an opportune time. Any one who has come into intimate contact with this product will instantly avow his surprise at finding so many graduates who reveal no discernible traces of their four-year contact with the things of the mind to differentiate them from others. To what purpose is this waste—for waste it must be if one who has spent four years and several thousand dollars in the supposed pursuit of education shows no sign of being educated ? Is there, really, any sufficient indication that this flood of college-trained citizens is as yet leavening the whole lump of our citizenship? It ought to show by this time, if democracy is to be deemed "a quality product."' Too few college men have enough to show for what they have done with their time. Too many have been educated just enough to make them unwilling to recognize their own limitations and fitnesses, acquiring false standards of living and very little else. It is time to combat this, so far as it may be combatted—and that we understand to be the great thought behind the introductory address of President Hopkins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT'S ADDRESS EVOKES NATION-WIDE COMMENT

November 1922 -

Article

ArticleAN ARISTOCRACY OF BRAINS

November 1922 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

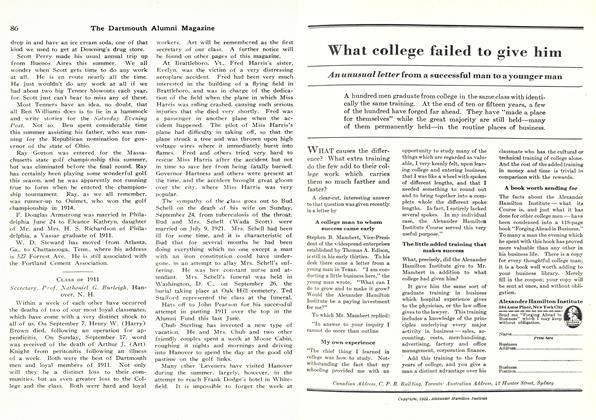

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1926

November 1922 By E. GORDON BILL -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL

November 1922