To the Editor DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE

Dear Sir:—The defence of the mental attitude of the graduating senior, which appears in the editorial columns of the MAGAZINE for August, if true, indicates a very fortunate change which must have taken place within the past few years. To be sure, most college seniors tell themselves over and over again that they are not conceited because of their education, and when they go seeking a position, after receiving their degrees, they approach their prospective employers with a humility that is quite in keeping with the spirit of the editorial in question. But one is impelled to ask whether this humility is exhibited because the youth really feels his incompetence or if the real reason is not that he expects the prospective employer to look with suspicion for the slightest evidence of overvaluation. He is, on the surface, a very humble creature, but at heart he believes that all he needs is "a chance" and he will immediately assume a prominent part in world activities.

Most men enter our higher institutions of learning with the preconceived idea that a college education is such an unusual thing in the world of affairs that the bachelor's degree is the open sesame to positions of the most lucrative sort. When they get out and begin their quest for such positions, if they be so unfortunate as to lack the personal influence which occasionally finds a man a good job, they soon learn that many of the men they approach as prospective employers are not college men themselves and are inclined to discount the youth who values his own knowledge of French and economics too highly.

If, as you say, "the American college graduate of today is sadly maligned by those who persist in displaying him to mankind as an upstanding young Crusader who is due for a terrible disappointment," why are such statements made ? Are they made by people who have never been through college and who are somewhat piqued by the cocksureness of the new graduate, or are they not usually made by college men who have been through the disappointing experience themselves ?

Whether or not the graduating senior has the proper valuation of himself, the fact remains that when he first comes in contact with the requirements of the business world he is astonished to discover how many necessary things his four years of preparation for a degree have failed to give him.

Every college graduate numbers among his acquaintances several classmates who occupy business positions for which the training of a year's course in an evening school would be far more useful than their four years of collegiate work. Statistics of an average class, one or two years after graduation, will show a surprising number of men who have not yet "found themselves". Sooner or later most of these men drift into positions where they seem to fit, but it is unfortunate that so much valuable time must be lost in the discouraging process.

Experience, the best of teachers, is also the most costly, and education endeavors to derive the benefits of the experience of others without spending so much time or making so many errors. But we cannot get it all from other people, and the newly graduated senior has little of it indeed. Few are the employers, to-day, who place the proper valuation on the ability a young tyro has as against the experience he lacks. The emphasis is altogether too strongly on the latter. Hence it is time that the college did something to give to the students a more effective substitute for the practical experience it is impossible for them to obtain.

The difficulty with the college is not entirely negative; it is not all due to the things the college fails to provide. There is a very positive element—false undergraduate standards, developed by immature students themselves and fostered by an indulgent faculty, which lead the men into misconceived ideas of their own importance and make it difficult for them to acquire "a true sense of values when the idealistic undergraduate world is replaced by one more practical, peopled by aspirants for fame and fortune who have been longer on the job.

Undergraduate life, except for those whose fortune—good or bad—it is to be working their own ways through, is unreal. Relieved from financial anxiety to a large extent and rather carefully segregated from the sobering influences of contact with practical affairs, the student is free to revel in the exploits of ancient heroes about whom he studies and to project himself forward, in fancy, into the future which, as yet, holds for him nothing but brilliant dreams. History, literature, sociology, and philosophy are his playgrounds, and while he romps in them he loses contact with the hard-headedness of a world that is interested in the accumulation of dollars and cents (although not so much the cents) or in the accomplishment of great industrial feats.

The college world is in many ways sufficient unto itself and tends to shut the student away from the world outside with its requirements and large scale activities. Each successive college generation has its playwright, its radical thinkers—and speakers—its outstanding poet, its religious leaders, as well as its campus executives and individuals with a trend toward activities of a business nature. In the minds of the undergraduates these men stand out in favorable comparison with the ones who occupy recognized positions in the world at large. They judge themselves and one another by the deference and importance conceded to them by their fellows. No wonder they find it difficult to adjust themselves when older and more mature men of the world are their judges and are less generous in the judgment they bestow.

To the student there is nothing quite so much to be revered as the senior in his . cap and gown representing—to him—the superlative or preparation for a life work. To the man who has been out a few years and has already nearly forgotten that he ever wore that regalia these youths are like the traveller returning from afar, whose house was burned in his absence and who has yet to learn the news. The discoveries that lie immediately before them are amazing, and there will be much disillusionment before these intransigeants rid themselves of the handicap which four years of rather monastic sequestration have placed upon them.

The big mistake many make is to aspire too highly too quickly. They need the advice an executive of one of America's leading manufacturing plants once gave to a young man who approached him in just such a state of mind and ambition. He said, "Young man, in this company, before a man can attain such a position as that which you desire, it is necessary for him first to put in a period of thorough training in the trenches. And the-Company has no trenches." Those words gave the youth the lead he had been seeking; he came to earth and went out, not to look for a vacant generalship, but to look for the "trenches" in which he could begin fighting for the necessary something that had not been given him with his degree.

The college is primarily responsible for graduating would-be generals. Whenever a speaker is secured to address the students on some phase of business activity, it is invariably a man who has made a conspicuous success and who is recognized as a "big" man in his realm. The result is to lead the students to believe that they are training to assume such positions themselves and that it will be but a few years after their graduation before they, too, will be looked upon as conspicuously successful men. The relatively unimportant positions—but, oh, so important in the development of the man himself—that the student must occupy at the outset of his career are never touched upon at all. How ludicrous it would seem to have the chief shipping clerk of a large wholesale house or the office manager of a manufacturing firm give the students a lecture on the rather menial work a new employee is called upon to do! But how much better it would be if the graduate could go forth with a realization that the first few years must be spent in learning the practical things the college could not teach and that the day when he will sit behind a mahogany desk is more remote by far than he has ever imagined in his most humble dreams! Why does not someone advance the heresy of having a few practical talks to groups of seniors by men who have but little "schooling" as such, who cannot speak English with even the polish of a high school graduate, but who can tell college students many things they will have to be told during the months immediately following their infliction on the world?

A young Dartmouth graduate said, not long ago, "I cannot recall ever having had it impressed upon a class in which I sat that the laws and theories which we were learning were simply the fruits of years of actual experience on the part of the very people with whom we were going to be thrown when we attempted to put our knowledge to work. Nothing was ever done to correct the impression we received that we were accumulating knowledge of a very unusual and superior sort, for which we would be paid handsomely as soon as we were ready to place it at the world's disposal."

It is an unfortunate man who thinks his education is finished when he is tendered his degree; and it is an unfortunate college that fails to teach the great truth that education, at least in the class-room, is merely "training oneself to learn" and that the accumulation of a practical store of knowledge must occur only in the world of business and industry. So long as the graduate is left to find this out for himself after months of stumbling around amid all kinds of discouraging set-backs, so long as the college fails to make smooth the transition from the class-room into the business world, the conceit of one type of commencement orator is an indictment of and the humility of another type is an apology for the shortcomings of the college itself.

Very truly yours,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

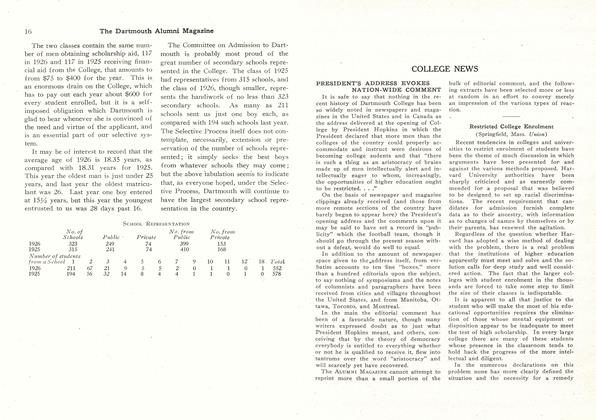

ArticlePRESIDENT'S ADDRESS EVOKES NATION-WIDE COMMENT

November 1922 -

Article

ArticleAN ARISTOCRACY OF BRAINS

November 1922 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

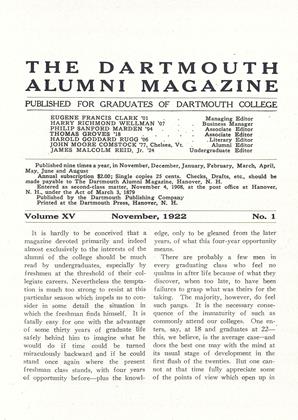

ArticleIt is hardly to be conceived that a magazine devoted primarily

November 1922 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1926

November 1922 By E. GORDON BILL