attention as adjuncts of the colleges. Within a few weeks the president of Harvard University has made public record of his belief that the spectacular element in college contests is being overdone—and this opinion, thus inadequately summarized, has been echoed by President Hopkins, by numerous alumni of various colleges, and by the daily press—which tatter is in itself more or less to blame for the fact that college football games have become "public shows".

One is forced to recognize another compelling reason which has produced this situation and makes probable its continuance; to wit, that in practically every college the receipts from the football season (augmented beyond those of other athletic activities) are so large as to afford material support for athletic activities in general. The football season, while very brief, is a prodigious money-maker—thanks largely to a game or two played away from home in some very populous centre—and has come to be the prop on which other athletic associations lean. This phase of the matter, while not agreeable, is none the less very real.

Revision downward, while generally commended as an ideal, has thus far no very practical exponents who seem disposed to do anything about it. The case suggests the average mayor's inaugural address in which economy is duly praised, only to be followed by a continuance of administrative extravagance. All of us, probably, believe that the college athletic paraphernalia are grossly exaggerated in modern circumstances, involving long trips—even transcontinental in extent—which ten years ago would not have been dreamed of by the smaller colleges but which are now common, as well as the maintenance of complex organizations and elaborate equipment, all of which runs into money. On such a scale as that, no college can easily conduct its athletics without public shows. The fact that there are such public shows is what yields the revenues. If the shows are to cease, then expenditures all along the line must be cut down. And while we all may inwardly agree that this ought to be done, who of us is especially anxious to take the lead in doing it?

It is admitted, we imagine, by every one that football is the one sport most characteristically collegiate which has nevertheless suffered the most complete divorcement from the academic atmosphere. The big games, played usually in big cities, certainly have little of the collegiate atmosphere about them and are rather frankly commercial enterprises when they forsake college playing-fields and seek such neutral territory as the Polo Grounds in New York, in response to public interest and local need.

It happens naturally that the public takes this interest. The game of football is a most exciting and interesting one, which the public likes to watch and which it has practically no opportunity to see, save as. it is played by college or school teams. Professional football does not exist—at least on any scale comparable to that of professional baseball— and probably never will exist on that scale, whatever be the trend of present experiments in the line of providing the public with professional teams. The public satisfies itself by seeking admissions to college contests—and the colleges, sore beset to meet the colossal expenditures of an ordinary athletic year, cheerfully provide the entertainment. For the average institution, this means that not more than one or two games in the schedule will be great producers of revenue for the support of all activities; but the one or two have come to be regarded as the focal points of the period of year covered by this sport. Intensive interest is concentrated on them. If huge stands sufficient to accommodate the expected multitude are not to be had at home, one may hire a disused ball park in New York, Boston, or Philadelphia- and one does so. A public exhibit of college football follows, and usually it "pays".

Is it right? Is it very wrong? Does it do any great harm? Does it do any discernible good? Hot partisans will readily be found to debate both sides of the question. And all the time it is easily possible that the middle ground is the more tenable ground—to wit, that the big football games are neither so good nor so bad as they are painted; and that while they do no very serious injury, they also do nothing like the amount of good which those always claim who talk of such things as "advertising the college." As advertisements of the college, we believe football games are the most grossly overrated agents in the list. They have their place and their value; but the value it not a tithe of what extremists are wont to claim.

To confine one's enthusiasm for the athletic side to its just proportion among other collegiate activities has never been an easy task. There is always the enthusiast who implies that the college really exists as an incident to its athletic prowess, rather than that athletics exist as a by-product of the academic life. By such it has more than once been soberly argued that the college did not well to tighten too rigidly its scholastic requirements, because thereby it discouraged a few intending applicants whose one desire was to play some game for the varsity, and thus tended to weaken the college as a whole. Against which, the argument is promptly made that if all a college exists for is to turn out superlative football teams, or baseball teams, the sooner it stops pretending to be a college and avows itself to be a mere athletic club the better.

This MAGAZINE must still believe that the best interest of Dartmouth depends upon making up our various teams of "Dartmouth men who are incidentally in athletics", rather than upon seeking teams made up of "athletes who' are only incidentally in Dartmouth." The attainment of a reputation for athletic prowess is not the be-all and the end-all here, but it is desirable enough in its way, and it does in its way assist the college, provided it is made manifest that this prowess is that of men who are primarily students and not mere gladiators whose presence in college is made possible only by letting down the bars.

It is easy to be too juvenile in estimating such matters. All of us, even those nearing the sere and yellow leaf, share the thrill when Dartmouth teams defeat their adversaries. But that thrill would lose its savors if one secretly knew the players to have been mere drones in the academic hive—men with no recommendation but their brawn, who had to be given exceptional handicaps on the intellectual line to retain them in college at all. That sort of thing Dartmouth must always refuse to do. It is not often argued for by Dartmouth men —even in the undergraduate stage of development; but it is argued for by a few in every college and in every alumni body by such as hold it the chief aim of a college to shine on the gridiron, on the diamond, or on the track.

If we may be pardoned one further word before leaving this moot subject, it is that Dartmouth's creed, as held by the overwhelming majority of her sturdy sons, excludes absolutely the idea of tempering scholastic requirements in order to get in a few stout lads with more muscle than mind to play football in her name. Grantland Rice, in his usually admirable sporting column in the daily press a few weeks ago, suggested a number of points that bear on this very situation of college athletics and their proper safeguard. The suggestions were seven in number and we crave your attention to them all—perhaps most especially to the tersely expressed second point which he mentions :—

The best safeguards for football are as follows:

1. A one-year residence rule where no first-year men are allowed to take part in intercollegiate contests.

2. A scholastic standing that no tramp athlete would care to meet.

3. If necessary a rule preventing any man from representing more than one institution in an intercollegiate way. The football player who wanders from one college team to another is rarely a help to the sport.

4. The refusal of the cleaner institutions with higher standards to schedule games with those inclined to be lax.

5. A stricter inspection of the field at large by colleges and universities of cleaner athletic mold, to see that all offenders are barred from their schedules.

6. To lift head coaches to faculty positions, where, as long as they are competent and are builders of character as well as builders of machines, they are not dependent upon successful scores alone.

7. To have no men selected for allstar teams that represent institutions of lax standards, and to give such teams no ranking at the end of the season.

By all means let us set scholastic standards that will bar out the "tramp athlete," whose one desire is to use the college as a means for displaying his aptitude for athletic contests, and whose membership in college must be safeguarded by deliberately lowering standards in his special case. The man who cannot stand even with his fellows in college requirements has no place on a college team, here or anywhere else. Rather than build up teams by lowering scholarship standards, the college would better take a beating in every department of sport, in every game. Fortunately it will not have to!

The first thing that strikes us about Mr. Wellman's suggestion of grouping the senior class in a new area in the Hitchcock estate, not only for purposes of classroom activity but also for dormitory and dining facilities, is that it exactly reverses the practice which Harvard has adopted in the housing of the freshmen in special quarters down near the Larz Anderson bridge. The principle is the same. The place of its application is, in Mr. Wellman's plan, at the other end of the undergraduate line. At first sight it strikes us that this plan is in some ways distinctly preferable to the one adopted at Harvard.

The seniors have had three years of direct college contact. The incidents of their closing year are such as to make their close association as a class desirable from the standpoint of those soon to emerge into the status of alumni. From the opening of senior year to commencement, the circumstances seem to us to make the segregation of that class less of a detriment to the college solidarity than would be the case if the newhatched,. unfledged comrades were similarly treated. In other words, if we may only preserve the attributes of a college of 1500 men by segregating one of the classes in a domain nearly, but not exclusively, its own, it is best to select the seniors for such segregation.

It is perhaps unjust to speak of this as "segregation", although the word seems to be the only one that fits. The Hitchcock estate is by no means remote —not nearly so remote from the college center as are the freshman dormitories at Cambridge. The daily contact with the college on the part of those living in that area and attending classes there would be but little curtailed. The advantages would be, in part the relief of the dormitories and other adjuncts of life for the intermediate and entering classes, and in part the cementing of class feeling for those about to depart and scatter to the four corners of the world.

The major premise is, of course, that only by some such cutting off is the result to be attained. This premise may be questioned, but is from a practical point of view apparently valid. Nevertheless we have no desire to dogmatize, either in its favor or against it, as a matter of first impressions. It is possible and desirable to walk all around it and consider it from every angle before committing oneself.

In the last previous issue of this MAGAZINE a chance item revealed the fact that a survey" made in 18 of the leading colleges of the country had shown a decline in the study of foreign languages of three and one-half per cent. Presumably by "foreign languages" is meant modern languages, in contradistinction to the classics. The falling off may be due to the transitory unpopularity of German by comparison with its recent vogue—for the survey covered only the past eight years, and in that time the conditions have been such as to produce the lessened popularity which we suspect. In the main, considering the clamor of the times for the confinement of instruction to the socalled practical" courses, it would seem difficult to account for a decline in modern language study, such being rated distinctly "practical" by the average opponent of the classical curriculum.

The standards generally employed for judging adversely the case of the classical studies may seem slightly unfair—indeed do seem so to many. It is pointed out that the student of Greek and Latin does not really learn to use those languages freely, even for the purposes of reading, and certainly does not learn to speak them. It is also urged that the student on leaving college speedily forgets what little he did know about those ancient tongues. One seldom pauses to reflect that the same student has equally forgotten what little chemistry he had absorbed, would be helpless if asked to state Boyle's law, and probably would confess his complete forgetfulness of what was meant by the binomial theorem, or an adfected quadratic equation. As for the modern languages as commonly taught in our highest institutions of learning, is it true that the majority of students learn to speak them, or write them, with fair idiomatic skill and fluency ? It may be admitted that the read- ing knowledge of French and German acquired by the average student exceeds that which followers of the classics usually' acquire. But after all is said and done the test of such studies remains more in their effect upon the mind of the student as an instrument for free and flexible use than in the ability of the graduate of 20 years' standing to remember the rules of grammar and a certain amount of the vocabulary.

All of which is a step aside, suggested by the chance information that foreign language study in 18 leading colleges had fallen off 3.58 per cent within eight years. It is a very small fraction of decline, but sufficiently large to arrest the attention and to lead to speculations as to the cause. A more marked falling off might easily lead to a movement to strengthen the language requirement for any sort of rudimentary academic degree.

The chart presented in the recent issue of this MAGAZINE showing in graphic form the set-up of the present organization of the college as drawn by Nils Wilhelm Horstadius should be of especial interest to the alumni as revealing in a striking way the relationship which exists between the alumni portion of the college organization and the mechanism of the college proper. Alumni representation in college management has been so broadly developed at Dartmouth and has grown up so gradually that it is quite probable the average graduate has only a hazy conception of its details. The work of Mr. Horstadius suffices to make much plain that has hitherto been rather obscure—at least it will be clear to such as have a ready power for the comprehension of the "graphs" of which modern engineering is so fond. To present an adequate graph in a single plane, of activities so complex in their relationship, is an extremely difficult task; and that of Mr. Horstadius leaves something, no doubt, to the imagination. But it comes so close to the ideal of showing, in a sort of aviator's-view form, the entire layout of the administration at a glance that its thoughtful study will amply repay any interested alumnus.

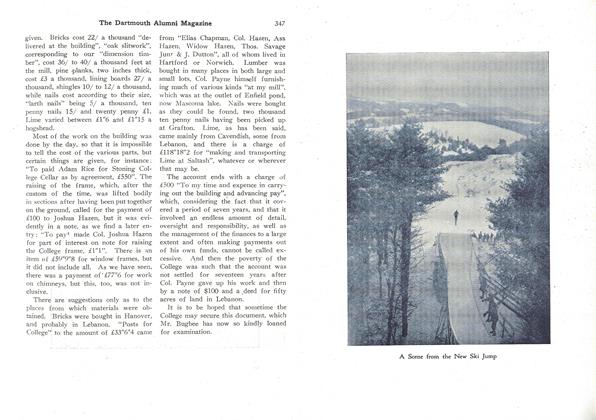

Winter at the Bema

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE DISCIPLINE

March 1922 By EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE GRANT

March 1922 By JOHN M. GILE '87 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS EXPOSES "FUNDAMENTALIST" MOVEMENT

March 1922 -

Article

ArticleTWELFTH WINTER CARNIVAL A HUGE SUCCESS

March 1922 -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

March 1922 -

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB CIRCULAR STIRS EDITORIAL PENS

March 1922