When a Hanover merchant's account book of Dartmouth students for 1799-1800 was unearthed a few years ago, the charges to Daniel Webster indicated there, especially those for liquor, led to the request for an article for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Sharing the traditional belief as Webster's "failings," the writer declined to prepare the article and suggested that enough on that subject had already been said. On being asked later to explain why Webster paid so much for liquor when in college, the writer proceeded to find out how much he did pay. As so often happens there proved to be nothing to explain. Webster spent not much but little. Of his total charges in Richard Lang's book, a mere fraction was for drink, and the amount for that purpose was found, on investigation, to be what was spent by the average student, and less than a tenth of the amount charged to President John Wheelock on the books of the Cornish lavern at a time when everyone used liquor.

Finding a local legend growing up before ones eyes, based on false assumptions, one was naturally led to ask what the real evidence was for other stories as to Webster's private and public character and his anti-slavery attitude. That enquiry opened up a long trail leading through a mass of a hundred modern books and pamphlets, back to hundreds of manuscripts of Webster and his contemporaries. The evidence in print, confirmed by that in Washington, Boston, Concord, and Hanover archives, shows a striking change in attitude toward Webster, and conclusive evidence on at least three points: his character, his 7th of March speech, and the secession movement of 1850.

The American public is not keenly interested in historical truth, was the complaint of a professor at a recent meeting of the American Historical Association. A colleague with a gift for epigram replied that this was true but it was also true that the American public was not keenly interested in historical truth as written by college professors. Facing this sad double truth, and still unterrified by forty years of experience of the power of the human mind to resist knowledge, a college professor may nevertheless venture to summarize the newer historical evidence on Webster and indicate the conclusion to which it leads.

The case is one of more than ordinary interest and importance. It concerns not merely gossip about a man's morals, but has become curiously entangled with the views as to Webster's public character and his attitude on the great moral question of slavery. Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Lowell, and Theodore Parker created a tradition which in a modified years after his 7th of March speech and the resulting attacks upon Webster's morals, before any extended critical study of the evidence as to Webster's character was published. In 1911 Professor Wilkinson of Chicago in his Daniel Webster,a Vindication (unfortunately now out of print), published the result of fifty years of investigation, showing conclusively both how the slander originated and how the charges not only lacked evidence but

were disproved by the very witnesses supposed to prove their allegations. He also showed there was ample positive evidence as to Webster's sobriety and uprightness on the part of those who were in the best position to know. A similar conclusion had already been reached in 1902 by Professor Van Tyne of Michigan as a result of going through the mass of Webster's correspondence and making some first hand investigation. Even one starting with a preconception of Webster's "frailties," as Wilkinson did, would be convinced by the overwhelming evidence of the contemporary witnesses, both in print and manuscript, that Webster has long been maligned through a combination of political partizanship and literary tradition. There is nothing to hide about Daniel Webster, as Mr. Rhodes pointed out thirty years ago. He was a man of large vision, and high standards of clean, wholesome life as

clearly evidenced by his own words and deeds and by the testimony of reliable men,—neighbors, friends, and servants in Marshfield, Alexander H. Stephens for years his next door neighbor at Washington, Edward Everett Hale and his father, his neighbors in Boston, and others who knew Webster intimately in his home life and hours of relaxation. Not only has no first-hand credible evidence ever been brought against Webster's character, private or public, there is no modern reliable account based on investigation of the evidence, which credits the charges.

In the last twenty years since the observance of the centennial of Webster's graduation from college in 1901, a mass of at least fifty publications have thrown entirely new light on his position and on the danger of secession in 1850. Van Tyne's Letters of Webster in 1902 and the eighteen volumes of the National Edition of the Writings and Speeches ofDaniel Webster, 1903 printed hundreds of letters for the first time, including 57 for the critical year 1850 alone. In the correspondence of Salmon P. Chase, Calhoun, Alexander H. Stephens, and others, now in print, the point of view of both anti-slavery men and southerners has been clearly revealed. The newer biographies and the monographs of a younger generation—happily freed by mere lapse of time from the bitterness of partizanship and trained in the modern careful collecting and sifting of evidence—have been based on examination of previously unknown material. Such studies as those by Ames and Hamer, on Calhoun and the secession movement in South Carolina, or Hearon on the movement in Mississippi, are examples of investigation which reveal in one southern state after another the real crisis in 1850 and the danger of active resistance even to the extent of disunion. Smith of Williams, Garrison of Texas, Chadwick of West Virginia, Stephenson of Charleston and Yale, in their volumes on the period preceding the Civil War still further illustrate the realization by recent historians of the disunion danger in 1850. Moreover we can now add to the matured conclusions of anti-slavery men like Whittier and Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, and of union men of 1850 like Foote of Mississippi and Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia, the recently published reminiscences of the younger generation of that day, Senator Hoar, Edward Everett Hale, E. P. Wheeler, and of J. K. Hosmer, typical of the boys of '61 who went to war. If we add to these later personal judgments the actual contemporary resolutions of the southern legislatures, the warnings'of the best qualified observers on the spot in the south in 1850, and the hundreds of still unpublished letters expressing judgments of the situation in 1850, and then see the overwhelming mass of testimony pointing one way, the conclusion is convincing to anyone of open mind that there was serious danger of disunion. No longer are we dependent as Rhodes was on the conflicting views expressed in the Congressional speeches as to the danger of disunion. The fuller evidence now available shows the growing menace of the secession movement in the southern states, the attempts of disunionists and extremists to develop this disunion, and the strenuous efforts required by union men like Stephens and Foote who had to go back, to Georgia and Mississippi to fight vigorous campaigns to check the rising tide. One sees a gradual swinging into line of southern legislatures in the winter of 1849-550, with measures for concerted action, appropriation of money, and other means for resistance, including sending delegates to the Southern Convention whose sponsors had called it in order tO stimulate united resistance on the part of the south. It is clear also that the southern extremists or "destructionists" were praying for such acts as the Wilmot Proviso, prohibiting slavery in the territory recently acquired from Mexico, which should so irritate the south as to throw her into the arms of resistance men at a time when she was in good condition to fight and the north was still disunited and unready. These disunionists one finds to be the same men who led secession in 1860, and almost without exception the Union men who like Stephens stood with Webster in 1850 for the compromise and against disunion, again in 1860 tried to check secession.

In the light of this new evidence, it has become possible to study the movement day by day until it becomes clear that the peak of the move for secession came in the critical three weeks in February and March preceding Webster's speech.

[EDITORIAL NOTE.—Lack of space compels the editor to omit at this point a portion of Professor Foster's article. The omitted passage presents a striking array of evidence, showing in conclusive fashion that during the crisis over the Compromise of 1850 there was serious danger that the southern states would attempt to destroy the Union if northern extremists were permitted to have their way and that Webster, realizing more clearly than almost anybody else the seriousness of the danger, made his famous 7th of March speech for the purpose of averting the evil byway of compromise, which was probably the only method that could have been used successfully. The American Historical Review for January contains an article by Professor Foster giving in detail the evidence he has gathered upon this subject and setting forth his conclusions.]

In two respects the 7th of March speech is greater than even Webster's reply to Hayne. In the first place the crisis was far greater, and his speech was of greater service to the country in saving it from disunion. No other man could have so swung northern sentiment and at the same time showed so conciliatory a spirit to the south. In the second place it took a higher degree of courage to face the disapproval of constituents than it did in 1830 to speak with their enthusiastic support. [As to the charge of treachery, there is no trustworthy evidence that Webster gave assurance that he would speak otherwise than he did. Winthrop has shown that the assertion of Giddings, cited by Lodge, that Webster had given assurance to the anti-slavery people is that of a witness not to be relied upon; and the whole tenor of Webster's correspondence rutis contrary to that assumption.] What Webster was deeply concerned about in 1850, as in 1830, was the preservation of the Union. The Union with him came first; liberty could come only through Union. His 7th of March speech was the culmination of a life-long effort to preserve the Union.

Senator Foote of Mississippi, recognized that Webster risked his popularity but that his arguments were unanswerable and swayed public opinion. Senator Hoar of Massachusetts, who in his youth condemned Webster, toward the end of his life (like Whittier and Wilson) recognized that "Webster differed from the friends of freedom of his time not in a weaker moral sense but only in a larger prophetic vision." He saw what no other man saw, the certainty of Civil War. "I think of him now....as the orator who bound fast with indissoluble strength the bonds of union." Hosmer has recorded the fact that his boy friends who went to war in 1861 were influenced more by Webster's speeches "as familiar to us as the sentences of the Lord's Prayer and scarcely less consecrated." than they were by the question of the right of secession. The letters of soldiers recorded by Senator Hoar reveal them pacing their lonely beat at night repeating "Liberty and Union," and writing "Webster shotted our guns."

There is overwhelming testimony both in print and in scores of imprinted manuscripts recording the quick response of men of all parties and of all sections after the 7th of March speech. [Even more significant are the later replies of such men as Mayor Huntington of Salem who wrote that he at first felt the speech to be too southern, hut "subsequent event at north and south have entirely satisfied me that you are right. .. .and vast numbers of others here in Massachusetts were wrong." "The change going on in me has been going on all around me." "You saw further ahead than the rest or most of us and had the courage and patriotism to stand upon the true ground." This unpublished letter is a specimen of the change in attitude of hundreds of cautious Whigs.* Webster's old Boston congressional district elected one of his most loyal supporters, Elliot, by a vote of 2,355 to 473 for Charles Sumner less than six months after the 7th of March speech, and the Massachusetts legislature overwhelmingly defeated a proposal to instruct Webster to vote for the Wilmot Proviso.] The anti-slavery accusation that Webster lost friends and caste and was himself "ill-at-ease" because of his speech is another piece of bitter partisanship. He did risk his reputation and the anti-slavery people did their best to make him lose it, and "it would" as Edward Everett wrote Winthrop, "have ruined any other man." His letters and those of his friends show him concerned about the Union, not about his political chances, with a serenity which surprised others. "The line of a sectional politician cannot fathom the depth of a national statesman," remains as true today as when written by Allen in 1852.

The postponement of Civil War due in considerable measure to Webster's statesmanlike, national and conciliatory attitude and his extraordinary influence in both north and south gave the north enormous advantage through the extraordinary progress which she made in 1850-1860 as compared with the south in population, resources, and determination to stand up for the union. She was not ready in 1850; but the boys like Hosmer bred on Webster's stirring devotion to the union were ready in spirit and in resources for the struggle ten years later.

Webster does not need defense against his erroneous and mistaken accusers. Rather do those need charity who failed to understand or who have misrepresented him and the crisis through which he helped to bring the nation. He is one of those great men who do not need us but whom we need to understand and if we would still catch his breadth of vision and See that Liberty comes through Union, and healing through co-operation but not through hate.

THE POPE PORTRAIT OF WEBSTER Presented to the College by Edward Tuck

The Webster Carriage

The Historic Plough

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

June 1922 -

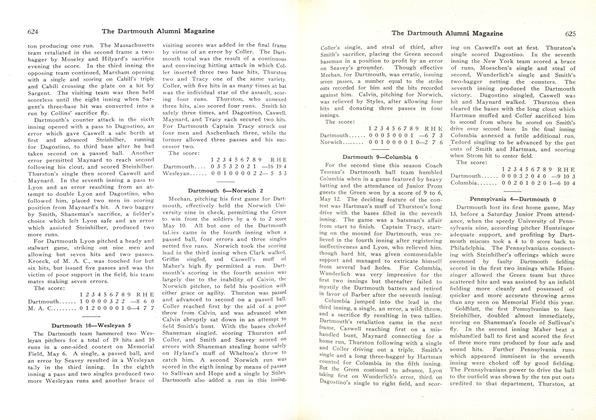

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

June 1922 -

Article

ArticleIt appears that the alumni fund is somewhat

June 1922 -

Books

BooksA Student's Philosophy of Religion

June 1922 By W. H. WOOD -

Sports

SportsTRACK

June 1922 -

Article

ArticleEXTRACT FROM RECORD OF TRUSTEES' MEETING

June 1922

Article

-

Article

ArticleINDOOR TRACK

March 1912 -

Article

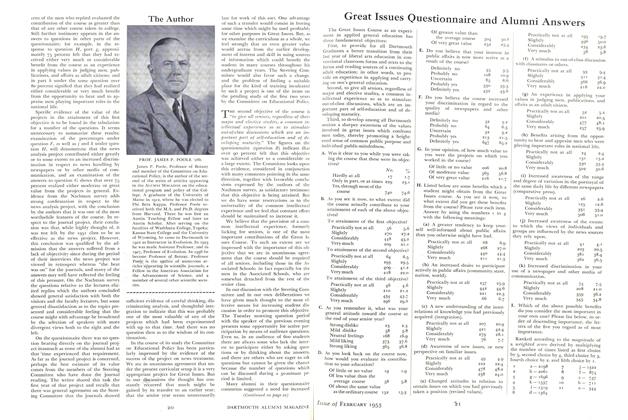

ArticleGreat Issues Questionnaire and Alumni Answers

February 1953 -

Article

ArticleMarshall Scholar

APRIL 1983 -

Article

ArticleSome Consequences of Inflation Psychology

FEBRUARY 1959 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL -

Article

ArticleNotebook

Nov/Dec 2004 By GEOFF HANSEN -

Article

ArticleUNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1935 By Milburn McCarty '35