Professor W. K. Wright. Macmillan Company, N.Y.

In this book Professor Wright of the Philosophy department has produced a work of very considerable proportions: 441 pages with introduction, additional notes, index and bibliography. The reading involved in the preparation for writing, the physical labor in the actual writing, -arranging and proof-reading, to say nothing of the value of. the product must have consumed many hours of patient and painstaking work. The conception of the courage needed to undertake such a task is in no way depreciated even though, "The book is an outgrowth of lecture courses given at Cornell University from 1913 to 1916."

The purpose of the book is stated "To furnish college undergraduates and general readers with the necessary data—facts and arguments-on which they will be able to work out their own philosophy of religion." The religious problems of students are stated as comprising questions concerning God, the freedom of the will, the problem of evil, the soul, immortality, church attendance and history of religions. The aim of the book then is to supply the data and arguments relating to these questions. However a section headed "The Author's Opinions" is given. The liberal spirit prevails throughout the work and the evolutionary viewpoint is slavishly followed.

The title is Philosophy of Religion. As is well known there is a PHILOSOPHY of religion and a philosophy of RELIGION. The first proceeds upon the assumption that philosophy is the universal and final systemmatized knowledge and wisdom, hence religion must be, and can be compassed, measured, tabulated and pressed into the philosophical system. Religion is therefore not an absolute. The second recognizes that religion is an absolute;" is not merely reflection upon life but life itself: is not a means only but the end in itself; is not a derived product but is an original; is not a Property of culture but a human property; is not a Part of life but life as a whole; is not a field for the application of theories only but creates and judges theories. With this distinction in mind it is expected that the philosopher or psychologist will follow the first line of thought while the religious student will follow the latter. Professor Wright follows the former hence he will find considerable "difference of scholarly opinion" concerning his work.

The book is divided into three parts with twenty-two chapters. Part One is entitled "Religion and The Conservation of Values" and through thirteen chapters attempts a definition of religion followed by an observation of the ways "in which ethical religions have developed from nature religions." Part Two, "Religion and the Self" is decidely psychological and deals with the religious sentiment, the development of the self, prayer and mysticism. Part Three, "Religion and Reality" is the philosophical or more exactly the metaphysical portion wherein the evidence of God, the nature of God and the problem of evil, God and human freedom and immortality are discussed. The historical approach to the study of religion is neglected.

It is always interesting when a thinker or writer goes outside of his own field, for then, the reader expects judgments and opinions unhampered by tradition or the FACH tendenz. The topics are the ones discussed and debated for many years by both the religious specialist, and the interested thinker, hence we turn immediately to ask for the convictions, principles and opinions of the writer.

Professor Wright's thought centers in two outstanding interests—psychology and morality. From the standpoint of these absorbing interests we can move to his basal convictions and hence to what he calls a philosophy of religion.

Psychologically considered the religious attitude is interpreted as sentiment. He does not use the usual term emotion but he might have just as well. The technical definition of religion given is: "The endeavor to secure the conservation of socially recognized values through specific actions that are believed to evoke some agency different from the ordinary ego or the individual or from other merely human beings and that imply a feeling of dependence upon this agency." This definition implies rational endeavor, rational knowledge of social values that are worthy and the rational relationship of men to a superior agency. It is just a little difficult to harmonize this definition with the one stated in the Preface and reinforced frequently, that religion is sentiment. Some of these other statements are that religion is primarily a matter of activity (emotion) of some kind or other; it is the expression of desire for some sort of value; a religion must be felt if it is to be really understood; religions are modes by which man advances. On the other hand it is stated that a religion is a certain kind of systematic effort to secure the conservation and enhancement of values. Perhaps sentiment means emotion developed into rationality. In any case religion is not an end in itself but a developed systematic effort to secure values. These values are interpreted as ethical rather than as religious which men usually value as the highest and supreme. The. author is at his best the farther he gets away from this all too prevalent conception of religion as sentiment or emotion.

In the realm of morality Professor Wright finds himself in his mood of greatest certainty. He believes firmly that this is a moral universe. He believes also that herein can one find the surest argument for the existence of God. So basal is this conviction to his thinking that he is inclined to think of religion as fundamentally a means to develop and help conserve moral values. "Religion always had a moral purpose."

Knowing these two supreme interests the reader will look with interest to the opinions the author will present concerning these age long problems. Prayer is primarily of value because of the effect upon the person who prays. There is added the belief that there is also some beneficial effect upon the body; upon the minds and bodies of other persons who are prayed for; and upon the physical environment. "From a moral standpoint we really could not desire that prayer were efficacious in any respect in which it is not efficacious." The main evidence of God is- found in the moral arguments. The view of Mr. Wells that God is finite and immanent is accepted. The Christian view that evil is to be and can be overcome by good is clearly urged. Religious freedom is discussed from the philosophical standpoint which worries over determinism versus freedom but the Christian wisdom that Christianity makes men free is not taken into account. The soul is not a separate personality but God has "become partly broken up into a lot of separate souls each only a fragment of His personality." We shall live immortally as a memory in God's mind.

If it be permissible for a reviewer to add a few words both of praise and of friendly reaction we would take this liberty. Professor Wright has thought long and earnestly on both religion and religious thinking and practises. He utters no immature opinions. A reverent and deeply religious spirit pervades the whole work. He is seriously anxious to help college men who may be struggling with religious problems. He has presented in accessible form much valuable material. It is refreshing to those who are making the study of religion their lifework to hear from thinkers in other fields whose interests lead them in this direction.

The few friendly criticisms that might be voiced are that the work would be equally as valuable with chapters two to thirteen omitted. Anthropology is not history of religion. An attempted psychology of religion is not the history of religions; the history of religion has not yet been written; and a philosophy of religion to be true to itself must be based upon the history of religions. Moreover the day should be past when thinkers place so much emphasis upon the lower forms and expressions of religion. If evolution means anything then the best and highest should be the norm. Genetic history and the thing itself are too often confused. The conception of religion which is the basis of the philosophy of religion will be to many a very unsatisfactory one. The pragmatic view here expressed touches but a narrow phase of religion. That religion is declared to have "no very specific and characteristic value of its own as have art, morality and science" will not readily be accepted. That men "employ a religion" for other purposes deepens this attitude. The opposite conviction of Hocking who is both philosopher and psychologist will find readier acceptance. He writes : "Our view of the effectiveness of religion in history does at once make evident as to its nature, first its necessary distinction; second its necessary supremacy. A merged religion and a negligible or subordinate religion are no religion." The Wells view of a finite God has been well described as Un oversize tire on the flivver of his self. The view of the soul and of immortality run too close to undiffer-entiated pantheism.

We hope the book will be widely read.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

June 1922 -

Sports

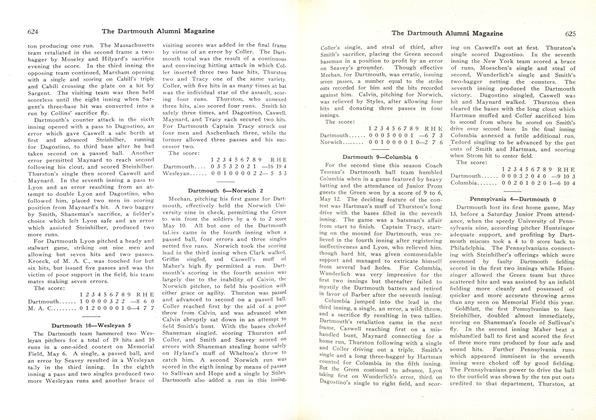

SportsBASEBALL

June 1922 -

Article

ArticleIt appears that the alumni fund is somewhat

June 1922 -

Article

ArticleNEW LIGHT ON WEBSTER AND HIS SEVENTH OF MARCH SPEECH

June 1922 By HERBERT D. FOSTER '85 -

Sports

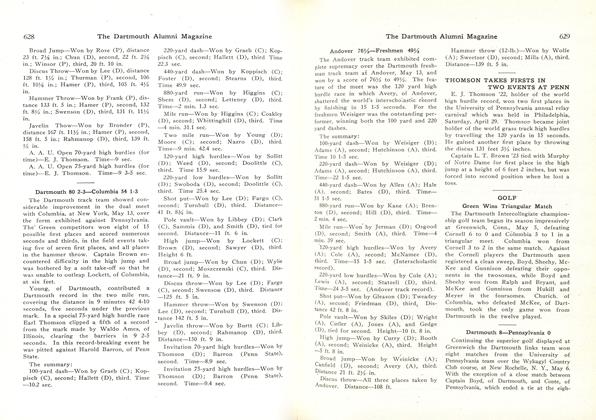

SportsTRACK

June 1922 -

Article

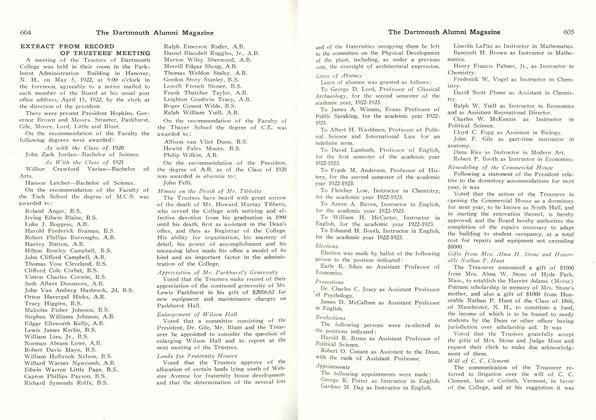

ArticleEXTRACT FROM RECORD OF TRUSTEES' MEETING

June 1922

W. H. WOOD

Books

-

Books

BooksHUMAN PSYCHOLOGY.

December 1936 By Charles Leonard Stone 'l7 -

Books

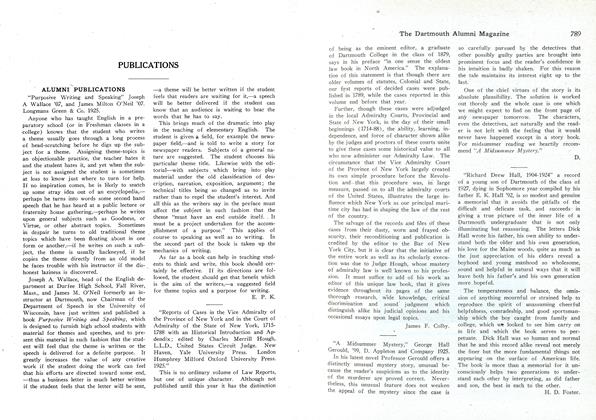

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

August, 1925 By James F. Colby, H. D. Foster -

Books

BooksHEARSES DON'T HURRY

May 1941 By Oliver L. Lilley '30 -

Books

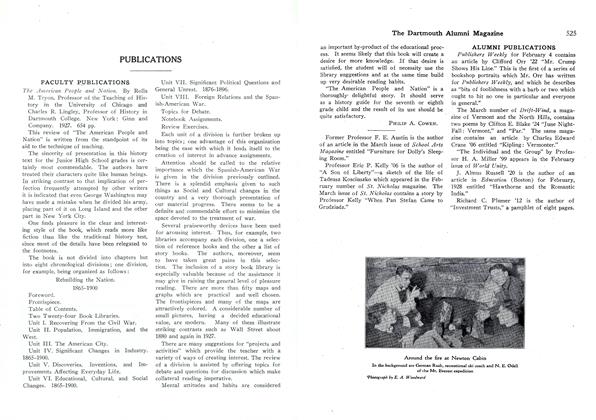

BooksThe American People and Nation.

APRIL 1928 By Philip A. Cowen -

Books

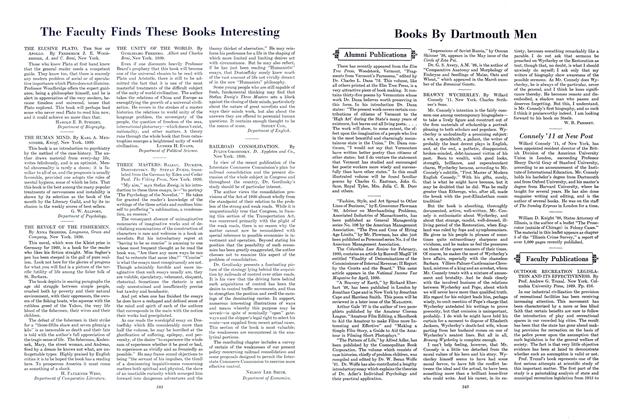

BooksTHREE MASTERS

JUNE 1930 By Sidney Cox -

Books

BooksA Tortured Process

MAY 1983 By William N. Fenton '30