year, adding one more to the already long list of Commencements since the days of Wheelock, prompts so many and such traditional feelings that perhaps the easiest way of expressing them is to refer the reader to prior years. There remains little that is new to say about a Dartmouth Commencement season. Once more the president and trustees have bestowed upon those deemed qualified to receive them the parchments which declare their recipients to be the qualified possessors of certain academic degrees; and once more several hundred young men have gone forth from the college to enroll themselves as worthy members of the alumni body.

The numbers which now go forth from Hanover in June are five or six times as great as the number that formed the average Dartmouth class of a quarter century ago. The incidents of their emergence remain substantially the same. There still abides that shopworn jest of the comic press which ascribes to all such an unwarranted self-confidence, not to say overweening conceit, which one is reminded will soon be knocked out of this hopeful army. May one say here that this seems rather unjust to a great body of young men and women, the country over, who enter upon what- they usually call "life in the Great World" with anything but a bumptious spirit ? Our observation of graduates at Commencement time predisposes us to sympathize with them, rather than perceive in them exponents of a self-sufficient egotism. There will be exceptions here and there in any college; but of most it will be found true that they enter upon "life" in a spirit of rather tremulous humility, asking only that the Great World take them seriously enough to give them work at very modest pay.

The traditional jest pays the old-fashioned valedictorian rather a compliment. It reads into his remarks at Commencement a genuine effort to bestow upon the world the inestimable gift of his personal opinions concerning the problems of life. Not enough allowance is made for the Commencement orator's real condition. His emission of these sage views is very probably not of his own choosing. He is probably ve;ry far from attempting to tell older and wiser men anything new, in any personal belief that he knows better than they what, if anything, is wrong with human society. Quite possibly he regards this performance as a chore which tradition demands as the incident of his having attained an uncomfortably lofty rank. His views thus publicly expressed are generally the views which are familiar to him as those of his instructors. What he himself will attempt to do, in event one hires him to assist in the conduct of some actual business, may not be judged too surely by what sentiments he feels it fitting to express on Commencement day.

At all events, such young men are not in fact, or as a rule, the arrant young asses the pert paragrapher's fancy paints — sure of their power to regenerate the world of which the elders have made such an unconscionable botch, and needing to have the conceit knocked out of them in the course of a rough experience. Many amiable delusions common to youth everywhere will no doubt be lost as years go on — for these young fellows are not very different from the rest of us, as we were at their age; but for the most part the American college graduate of today is sadly maligned by those who persist in displaying him to mankind as an upstanding young Crusader who is due for a terrible disappointment. Very few are guilty of regarding the sonorous Latin words of the diploma as a magical incantation, certain to open every door, or as indisputable evidence that the world owes them the duty of listening with awed respect to what they may say or think.

Let us do ordinary justice by the student just emerging from the college course, reasonably proud that the faculty have deemed him worthy of his A.B., or his B.S. It does not follow that he is unreasonably proud of it, or that he overestimates it. There is more reason to fear that because of the jibes of the jokers he may undervalue what his college has done for him, and may have even less of self-confidence than he ought to have in facing the problems of earning a living. The baccalaureate is an honorable estate. It should no more be belittled than overestimated. These young people are not fools, remember. They are very far from that. They are not deluded as to their own importance half so surely as they are deluded concerning yours.

At the recent meeting of the Association of Class Secretaries at Hanover several topics were discussed which seem to merit further reference here. It need hardly be stated that this annual gathering of secretaries serves a most useful end, in that it brings together in a meeting of workable size representatives of practically the whole alumni body, both older and younger graduates, for the interchange of views on terms of informal intimacy. At the recent meeting the assembled secretaries represented alumni for practically 60 years.

The subjects discussed with the most fulness were two — the ALUMNI MAGAZINE and the method of electing trustees. We may be pardoned, therefore, for taking up both briefly; and especially the matter of the MAGAZINE as a topic most intimately familiar to ourselves.

It was suggested that the MAGAZINE would better serve the requirements of the alumni as a purveyor of college news if it appeared more frequently — even weekly — instead of only once a month for nine issues. This suggestion assumes that one function of the MAGAZINE is properly the dissemination of news (while it is still fresh) concerning the regular activities of the college, both educational and social, athletic and academic, for the information of the alumni body. It is admitted on all hands that a monthly publication seldom does this with real efficiency. Any reader will have noticed that, weeks after the close of the football season, the pages devoted to college activities were still giving the scores and brief accounts of games already halfforgotten. But there arises in the mind a query whether this points to the more frequent issue of this MAGAZINE, or to the modification of its endeavors in this special field. The present editors entertain little doubt that the latter is the more feasible interpretation if any change is to be attempted.

In a survey of the possibilities provided by Professor Wellman, it was indicated that the cost of an alumni weekly would be so great that in all probability the subscription rate per annum would require to be doubled, or nearly so, if the publication were to come as close to paying its own way as the MAGAZINE now does. One may be pardoned for a doubt as to the readiness of the alumni to pay so great a price for the prompter service. To double the fee and halve the number of readers would seem inadvisable; and that is one of the serious probabilities, in our judgment, of the weekly plan if it were ever to be-adopted.

It is also a fair question whether even a weekly issue would sufficiently cure the defect to warrant its existence. It is admittedly impossible for a monthly magazine to perform the functions of a daily newspaper. It is a better approximation when a weekly publication seeks to summarize the deeds of a given week, but even that falls short of entire satisfaction. Wherefore it is respectfully suggested that perhaps the more defensible solution would be to have the MAGAZINE recognize quite frankly its lack of facilities to purvey fresh athletic and social news, at least with anything like the detail possible to the Daily Dartmouth, and attempt to deal with such concrete events more generally.

There appears to be some doubt as to what extent the alumni really require detailed news as contrasted with more general information. It is unquestioned that the bulk of the alumni will obtain their knowledge of the outcome of the more important games, throughout the various athletic seasons, from their Sunday newspapers at home. Naturally a magazine coming along a week or a month later will have a warmed-over taste, so far as it seeks to give an account of that game. Indeed that section of the MAGAZINE has seemed to have importance chiefly as affording a convenient and condensed seasonal record, rather than as a lively news department.

We are compelled, in view of the difficulties both practical and speculative, to adopt the view that if any alteration is made it would better be in the direction of a modified scope for the monthly, than an effort to give the MAGAZINE a weekly form. The defect which lies at the bottom of the problem is evident enough and is frankly admitted. It may be that the MAGAZINE errs in attempting to deal with current news, as news, at all, since the exigencies of make-up and preparation are bound to entail some delay, even in reporting the most opportunely recent events. The monthly publication must of necessity adapt itself to a monthly field. Attempting to make it partake of the daily news field is bound to result in something approaching failure, so far as freshness goes.

The method of selecting alumni trustees is a more perplexing problem. The discussion at the recent meeting arose chiefly from the fact that the preliminary canvass, made by the Alumni Council at the instance of the Alumni Association, had led to the suggestion of a single name instead of several, thus making the process of an alumni vote purely a ratification of a choice already made by representatives of the whole body, rather than a choice by the entire electorate among several nominees.

Naturally the opinions differed widely. No one, so far as appears, has denied the high excellence of the resulting boards of trustees; but it has been felt by many that "the spirit would be better" if the actual choosing were done by popular vote, instead of by a delegated convention to be ratified later. There is so much to be said for both sides of this question that the MAGAZINE does not feel itself justified in taking up the cudgels for either. But it may be said without impropriety that, after all, the main thing in view is necessarily the choice of the best possible body of alumni trustees, to which matter purely methodological questions would seem to be distinctly subordinate. It would be unfortunate to confuse means with ends, or to ascribe to mere methods more virtue than to the results to be achieved.

Speaking generally, almost too much is usually demanded of every electorate, under a purely democratic system, to enable the highest efficiency. This has had its best illustration, perhaps, in the failure of the "direct primary" method of making political nominations—a method which can work well only where the electors are in fact, as well as in theory, alert and anxious citizens with nothing in mind but the most enlightened civic action. Sad experience with the direct primary, may have sufficed to weaken the enthusiasm of many alumni for an application of much the same principle to our trustee elections. No one greatly relishes the confession that full democracy leads generally to a lessened efficiency; but that expression has nevertheless become fairly common with regard to political affairs as the result not only of direct primaries but also of direct senatorial elections. One flies from evils that one has, to others that one knows not of, in most such cases; and the evils that one knows not of frequently turn out to be somewhat less tolerable than those abandoned.

Some such reasoning as this was embodied in the remarks of those who defended the present situation in the matter of presenting single names of candidates for ratification. Deliberation over the numerous original suggestions, one was told, has always been profound and painstaking on the part of the alumni delegates who conducted the canvass — more so, perhaps, than would have been possible had the whole array been put on a single ballot sheet, together with biographical sketches, and transmitted broadcast to the alumni for their final election. One has to remember that great bodies of men, especially when widely scattered, do not function with that inalterable precision which the fancy paints when theorizing about their actions.

Recent disclosures at Princeton, indicating that certain students of marked athletic prowess had been led to select Princeton as their college because of financial assistance extended to them, have led to a protracted discussion in the public prints and elsewhere. It has been noted that the action of college authorities, in attempting to weed out men from athletic contests whose situation was of this character, met with some little resentment on the part of many devoted alumni and to some efforts at a defense °f the practice of offering financial assistance in procuring an education to promising young men discovered playing good baseball or good football on preparatory school teams. There is a well formed sentiment in. some quarters that this custom—which is by no means localized in any one college or section — should be approved, on the same principle as that by which one approves scholarship assistance to non-athletic students.

At the risk of inviting some hostile criticism, we incline not to take that charitable view of it. There may appear to be a lack of logic in applauding alumni funds to assist young men through college as a purely philanthropic matter, while one condemns the raising of funds to allure promising athletes to choose one college rather than another. It may be assumed that the athletic young men are in such instances bona fide students and also that they are usually in need of aid. The trouble is that the motive which induces the subscription of scholarship funds to insure the presence of a few athletic experts is not in its essence philanthropic, but bears more nearly on a covert species of professionalism against which most reputable colleges are struggling. The real reason for generosity toward these men is not a bland desire to educate the needy; it is that star performers may be secured to play on the team, or run on the track — not for their own intellectual benefit so much as for the benefit of the college athletic record. In such cases the philanthropic guise is the merest camouflage. The ulterior motive is to strengthen the team.

Admittedly this particular form of professionalism is indirect and is less irritating to the conscience than other and balder forms. But to any one with the proper attitude of mind it appears to us the practice must seem tainted with a certain lack of propriety. In theory a college sends forth to do its battles in contests with other colleges men who are primarily its students, and who are athletes as an incident only. In practice, too many star performers have been athletes first and college men afterwards.. President Hopkins put the principle as succinctly and tersely as it can be put when he remarked a short time ago that it was preferable to have our own college represented in its games by "Dartmouth men who are incidentally in athletics, rather than by athletes who are incidentally in Dartmouth." It is difficult to find, in the case of young men who have been induced to choose a given college because of financial assistance due to the knowledge of their athletic prowess, the proper set of conditions for ideal sport. There s a difference between subscribing to a fund to enable worthy young men to get a college education and subscribing to a fund designed to recruit the various teams: One suspects it is rather too widely done. One feels, however, that a strict standard cannot approve it, partly because it assails the problem from the wrong end and lacks but little of forthright professionalism, in its main features when analyzed.

Nevertheless there are bound to be in every considerable body of alumni in any college numerous enthusiastic and devoted men who not only defend the theory but who also resent, as has apparently been true at Princeton, all efforts to oppose it. There is so much genuine, if mistaken, loyalty in this that one disapproves with reluctance and regret; but it still seems to us that the whole attitude in such cases is wrong and that it tends to derogate from the higher standing of our colleges to treat them as if to shine in various lines of sport were the first and great commandment.

Every year, unfortunately, brings with it that melancholy record, the necrology. It is but a few weeks since, at the meeting of class secretaries in Hanover, one of the most prominent figures was that of the venerable ex-Governor Pingree of Vermont, representing the class of 1857 — a man apparently still hale and hearty despite his nearly 90 years. In the interval he has died — full of years and honors and equipped with all that should accompany old age — one of the college's oldest and most reverenced alumni, whose fortune it was to reside so near to Hanover that his presence was almost certainly to be counted upon at any college event. Few members of the secretaries association have been so constantly devoted as he. Almost in the same week his honored class mate, Judge John C. Hale, died in Cleveland, mourned by the few surviving alumni of his generation and in Dartmouth circles generally. Other losses include W. T. Abbott '90, a former president of the Alumni Association, remembered as the presiding officer at the alumni observance of Dartmouth's sesquicentennial. Also "Jack" O'Connor '02, whose genial energy went so far to create a working body of enthusiastic Dartmouth alumni in the city of Manchester, N. H., where he had his home. All these, to name no more who are beyond doubt equally worthy of mention, were thoroughly typical of that mysterious essence which we call the "Dartmouth spirit," embodying in their lives the unquenchable loyalty which a worthy college invariably inspires in worthy sons. Which may it do forever!

The MAGAZINE cannot allow to pass unnoticed or uncommented on the fact that Gen. Frank W. Streeter has just completed his thirtieth year of service as a trustee of the' college. It has been the rare good fortune of Gen. Streeter not only to witness during his term the amazing development of the new Dartmouth, but also to be pars magna thereof himself. Few other members of the governing board of the College have ever served so long or so energetically, and none with a better heart for the work, or a saner enthusiasm for what Dr. Tucker would call "the higher ranges of the practical." The zeal and loyalty of Gen. Streeter have been an inestimable asset to the college throughout the period of his service - now amounting to what men usually call a generation — and beyond question will continue so to be, while strength and vigor are still vouchsafed to this well loved and self-sacrificing servant of Dartmouth. Unstinted devotion of this sustained and sustaining character is an inspiration to us all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1922

August 1922 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94 -

Article

ArticleTHIRTY YEARS

August 1922 By PROFESSOR JOHN KING LORD '68 -

Article

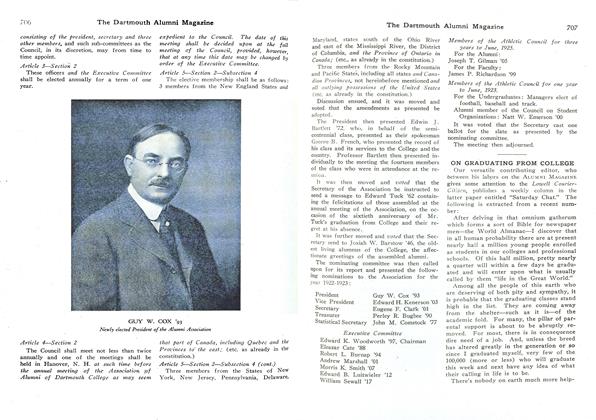

ArticleALUMNI COUNCIL MEETS IN HANOVER

August 1922 -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

August 1922 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

August 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleON GRADUATING FROM COLLEGE

August 1922

Article

-

Article

ArticleDEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS GETS EGYPTIAN BAS-RELIEF

AUGUST, 1927 -

Article

ArticleA Gateway to the College

March 1942 -

Article

Article"Eleazar" Ahoy

May 1942 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1918 GATHERS FOR ITS ANNUAL POMONOK OUTING RECENTLY IN NEW YORK

November 1946 -

Article

ArticleGlee Club Will Perform in Madison Square Garden

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Article

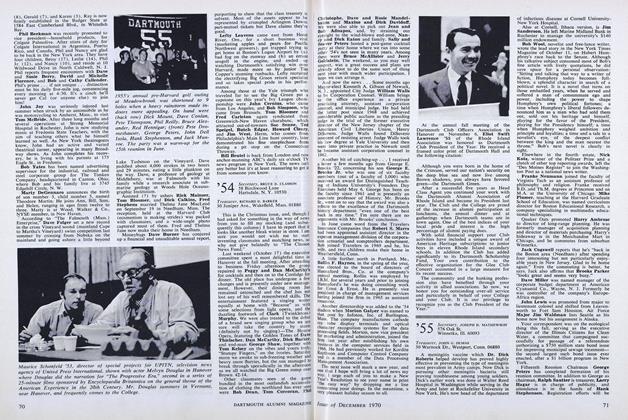

ArticleAt the annual fall meeting of

DECEMBER 1970