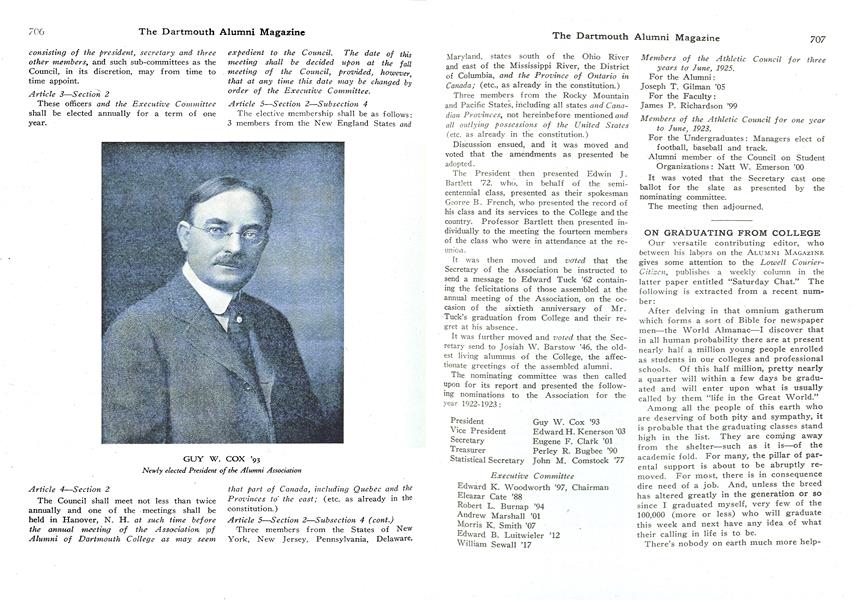

Our versatile contributing editor, who between his labors on the ALUMNI MAGAZINE gives some attention to the Lowell Courier Citizen, publishes a weekly column in the latter paper entitled "Saturday Chat." The following is extracted from a recent number:

After delving in that omnium gatherum which forms a sort of Bible for newspaper men — the World Almanac — I discover that in all human probability there are at present nearly half a million young people enrolled as students in our colleges and professional schools. Of this half million, pretty nearly a quarter will within a few days be graduated and will enter upon what is usually called by them "life in the Great World."

Among all the people of this earth who are deserving of both pity and sympathy, it is probable that the graduating classes stand high in the list. They are coming away from the shelter — such as it is — of the academic fold. For many, the pillar of parental support is about to be abruptly removed. For most, there is in consequence dire need of a job. And, unless the breed has altered greatly in the generation or so since I graduated myself, very few of the 100,000 (more or less) who will graduate this week and next have any idea of what their calling in life is to be.

There's nobody on earth much more helpless than the callow boy just emerging from his senior year in college, who has no clear notion of what he wants to do, or is fitted to do.

My heart goes out to such. I can so easily throw my mind back about 30 years to the moment when I was handed my sheepskin by dear old Prex. I remember that five of us took a brief walk that afternoon to say farewell to old familiar scenes and that Bob B. voiced a common thought when he said, ' Boys, I wonder where each of us will be a year from now?" And Sherm had retorted contemptuously, "A year from now! Say five years!" Out of our class, which was not a very large class, a few had made up their minds. The bulk of us not only hadn't made up our minds, but had nothing much to make them up about. We just knew we wanted a job — rather modest were our notions of what it was desirable we should be paid — and I suspect every one of us was desperately in love with some girl, whom he had every hope and intention of asking to accompany him through life, which added an incentive to the search for remunerative work. I wonder how many of that little company of five married the girls they were so sweet on then? I think at our next reunion I shall ask.

As I recall this casual group they turned out rather well. Bob, who asked the question first, has become a railroad potentate. Another is in Congress. Another, after serving as governor of his state, is in high official position at Washington. Tuffy is a professor. J. is the primal mogul of one of this country's greatest and most prosperous public utilities. Your humble servant is the exception. He is a hack-writer — turning into copy in 1922 the recollections of what happened about 30 years agone. The funny thing about it is that I am probably the only one of the five who is today in just about the "job he half-expected to be in. I might except Tuffy, though — for he was always inclined toward teaching. The others started out in other lines and became what they became seizing opportunities as they developed — and they were the really successful ones of that little group.

Senior year is a pretty good year. It isn't so good as junior year because the thoughts of separating from the familiar groups and of earning your own bread and butter keep recurring, as the senior weeks roll on. The junior can forget this rumble of a distant drum, where the senior finds it harder and harder. I think junior year in college is the happiest possible time for the rising generation — when one is possessed of the dignity and authority of an upper-class-man without all the burden of choosing a career. Of course you have much more dignity, and at least in your own sight much more importance, as a senior; but you can't enjoy these things with perfect freedom any more. Soon you will hear Prexy admitting you to the goodly fellowship of the bachelors of arts and telling you that he endues you plenteously with whatever "privileges, immunities and honors" go with this degree. (It would bother him if you asked him what these are; I have not discovered that there are any.) But he says he bestows them; and you gratefully, take the parchment cylinder in which, with stately Latin phrase, the "Praeses et Socii" admonish "omnibus ad quos hae literae per- venerint" that you are actually an A. 8., whether you look it or not.

In the seclusion of your half-dismantled room you unroll this portentous screed and discover what a hash the perplexed scrivener has made of trying to Latinize your first two names — and, what is still worse, put them into the accusative case. I believe they once used to Latinize the surnames as well, until the absurdity of "Smithum" and "Johnsonem" became apparent even to the faculty committees. Possibly they have cut out the whole stately business now — but I hope not. There's little enough in your A. B. without depriving it of these mysteries and thrills due to the sonorous Roman verbiage. In my day the president called out your name and handed you your own diploma. In these days of whopping big classes* this is done away and the long file snatches its parchments as it passes a desk, probably getting the wrong one which is rectified later by the swapping process.

I don't know how it is in other places, but at Siwash "where I received my well rounded education it was once the custom for the valedictorian to pause, after he had enlightened us as to the latest views of the atomic theory, or the latest wheeze about applied eugenics, and turn to his sweltering auditors with some such vocative as "Comrades," or "Classmates," and launch into a brief expression of farewell. The faculty were roundly thanked for their endeavors and much sob-stuff about Old Siwash was invariably spilled. They don't do this any more. The only way you can tell who is valedictorian now is 'to note the asterisks and daggers appended to the names — the timetable signs which usually mean "does not run on holidays" or "no baggage carried on this train" — for what he says gives no clue.

Likewise the salutatorian, who in my remote age was wont to pour forth his broadside in Latin, so that even though you might know nothing of Cicero and Sallust you could at least tell that he was firing the class salute, does this no more. He, too, is identified only by reference to the fine type at the bottom of Page Two. I wonder if this is for the best? It shortens the agony, on what is invariably by God's providence the hottest day of the year. But there is lacking some of the ancient spirit which went with the departure of a seasoned class of Siwash men to do battle with the Great World. I somehow feel about it as I do about a dinner unblessed by any dessert. The Latin salutatory used to come, as Carolyn Wells would say, "like the Benedictine that follows after food." It was probably very sad Latin — although it was corrected by the head of the classical department. It made rude jests about townsfolk and neighboring rustics which they couldn't comprehend — and which the class itself didn't really understand, although they laughed as in duty bound at the proper Points. But I miss it, now that it is gone.

These young fellows suffer also from the fact that they are spoken of as "choosing a career." The sound of that implies that they are so cocksure of success that all they need do is look around and say what line of work they'll condescend to take up. I doubt that many of them really feel that way. I am certain that most of them humbly hope some career will choose them. It's easy to say you'll study medicine, or study law, or go into engineering, or business, or the church. But that proves very little beyond the fact that you have a vague idea that you'll like some one of these possible careers, or that they'll turn out to be what you are suited for. One has to prove what's what by experiment.

Meantime, note well that the more progressive business of the country actually sends out its scouts among the colleges every year looking for promising material—just as the big leagues send scouts out through "the minors." Big business has discovered that this pays. I have been told within a few months by an alert New England newspaper manager that he will not accept for his editorial force any man who cannot show an A.B. degree—which is a mighty good rule. So those "privileges, immunities and honors" we oldsters are so fond of poking fun at, may really exist after all!

To the graduates of the class of 1922, then, from whatever college, university or professional school they hail! God bless them, every one !

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1922

August 1922 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94 -

Article

ArticleThe closing of another college

August 1922 -

Article

ArticleTHIRTY YEARS

August 1922 By PROFESSOR JOHN KING LORD '68 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI COUNCIL MEETS IN HANOVER

August 1922 -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

August 1922 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

August 1922 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh