Willard M. Gooding ' 11, Rarely in the Limelight, Keeps the Plant Ticking

PRESIDENT WHEELOCK had no need of a Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds. Indeed he boasted of his house as being no more complicated than a "Hutt in the Hanover Woods" with construction so simple as to contain no stone, glass, bricks, or nails. President Dickey's house contains all four items and cost $132,000 when Edward Tuck '62 presented it to the College in 1925.

In 1770 Dartmouth had a single log hut as the educational foundation to educate and instruct the youth of the Indian tribes in reading and writing and to civilize and Christianize pagan children. In 1950 Dartmouth has a plant of 175 acres of grounds and some 60 modern buildings valued at more than $11,000,000.

A modern superintendent of grounds and buildings has probably more diverse problems to solve than any other college officer. He could even have solved President Wheelock's if he had had to, ones like finding white boys to drive the cows to pasture when the Idian boys proved incompetent or hiring woodsmen to fell white pines that rose 100 feet above the campus before a branch appeared and on up to 270 feet to the top.

Even during the 1770's in that forested wilderness known as the Hanover Plain, forces were at work which brought into being a superintendent of buildings and grounds, a man with enough shrewdness to know how a job can be done quickly and enough persuasiveness to get someone to do it when he cannot find time to do it himself.

President Wheelock worried about the spirituality of his students. He also worried about his welldiggers who in one place sank pipes 63 feet into the Plain and failed to get water and about a hemlock swamp, where' the football field is now located, which contained so much water that corduroy roads had to be built across the treacherous muckiness.

In 1950 the Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds has come to his full development. He has become as vital to the ticking of the College as a main spring to a watch and is perpetually working in obscurity behind the face of things. He is Japanese beetle expert, engineer, plumber, forester, landscape architect, water procurer, road builder, employment agent, and disciplinarian. Indeed, if Mr. Gooding should absent himself long from the Hanover scene, trouble would flow in through the front door of the Administration Building into his office and if not stopped there (it might be temporarily by his assistants) flood past Dean Neidlinger's office, past the Registrar's and the Treasurer's and up the stairs to the President's. Life would resemble the hemlock swamp and the corduroy roads of the 1770'5.

WILLARD M. GOODING '11, a thickset but rapidly moving efficiency expert, has just completed 30 years of work at Dartmouth and has nearly all the answers. He knows all the tricks about steam and boilers, illegal electric stoves, broken windows, plugged waterclosets, landscaping with honeysuckle and Southern pines, beer riots on Saturday nights, fire extinguishers and their proper use, rats and cockroaches and their hideouts, the amount of oil Dartmouth burns yearly (it is 2,300,000 gallons), and the amount of hot water Dartmouth boys use in showers. Mr. Gooding operates so efficiently and so unobtrusively that he is little known on the campus or on Main Street except by sight and by reputation. During Mr. Hopkins' administration, Mr. Gooding went only twice without appointment to the President's Office. You will not find him passing the time of day in Tanzis fruit store or hobnobbing with the faculty in the post office.

He may be in his Parkhurst office trying to figure out the way to be all things to all men and women in matters concerning homes and offices. He has the gargantuan task of trying to run the Dartmouth plant economically and at the same time to please everyone who would like improvements ranging anywhere in expense from a dime to a hundred thousand dollars.

Take heating. "It is a major problem," says Mr. Gooding, "to please more than 4,000 persons at Dartmouth who come to Hanover from all sorts of climates and environments. They may have 4,000 different ideas of what they need and wish for heat, and the actual requirements will vary according to what they have been accustomed to before coming here."

A welcome visitor at the Office of Buildings and Grounds is not that man (or woman) who insists that the College owes him 24-hour steam in his radiators and complains amidst the July heat that it is off. The most annoying of all complainers may be those persons who are not cold at the moment but are worried that they will be. In 1949 Mr. Gooding received more complaints on this score than any other.

This aspect of his work may lead one to wonder whether at times he is a frustrated man incapable of acting quickly and rightly. On the contrary, he can move with detached efficiency and wisdom. In an unprecedented situation he can make an intuitive and correct response and act after the impulse.

When the White Church was burning down in 1933, the biggest and unhappiest of all campus bonfires, Prof. Chester H. Forsyth '3911 turned to Mr. Gooding and said, "That's a sad sight." Mr. Gooding replied quickly, "We'll have that cellar hole filled up right away and grass growing in two weeks." Fourteen days later the lawn was greening up nicely. Such is the speed with which Mr. Gooding operates with the help of Nature and his men.

Every important executive is said to have a specialty. Mr. Gooding's is purchasing. That may be the one activity to which he gives more time and thought than to any other. He has saved the College a lot of money by his ability to act quickly. If he hears that the price of oil is going up, he makes a fast trip to Boston or a telephone call to make sure that the plant can have shipped in as much as it can take care of. Though he shops around, he does not succumb to the temptation to assume that the cheapest is best; it is no economy to have machines in laboratories and power plants periodically out of repair.

Mr. Gooding is in a hurry always; his job is never done. But his manner, once he is approached on business, is relaxed. And he is relaxed when he approaches others on business. He can and does surprise grocery clerks, for after assembling a large order he nonchalantly totes up all the figures in his head, and before they can so much as lick a pencil preparatory to jotting down the costs of the 21 items, he will say $13.27. Sceptical clerks sometimes juggle twice through their addition to get the answer that their customer did instantly and correctly in his head.

A SUPERINTENDENT of buildings and grounds is self-taught; he learns by doing. Though Mr. Gooding has a civil engineering degree (Thayer School '12) and though he worked for nearly a year with a consulting engineering firm in Boston and for more than seven years as Superintendent of the Berlin Water Company upstate, he does not believe that such backgrounds have helped him much. "You just have to pick it up as you go along," he says. "There is no place in the world to get specific training to become a superintendent of buildings and grounds except at another college."

It is one thing to run the Berlin Water Company; it is another to oversee the Dartmouth plant. It is big business. Mr. Gooding has approximately 250 men on his payroll. The 400-0dd apartments for faculty and married students are merely a minor item, though if Mr. Gooding had the recklessness to treat them as minor it would be major. With war brides and babies Sachem Village and Wigwam Circle have kept more than fathers on their toes with highpitched demands for service and comforts. Babies and brides have mostly moved on, but Sachem and Wigwam linger on in their impermanence. Dormitories with their 2,000 students are relatively major, but they seem to shrink against the background of the whole plant.

When Mr. Gooding took over his job in 1920, four years after Mr. Hopkins had been made President, a sightseer could have stood in one spot and viewed the whole of Dartmouth College. Shortly after Mr. Gooding began familiarizing himself with the status quo, the status quo began gushing like a Texas oil field, and the Hanover Plain sprouted with the frameork of buildings. It is unlikely that the College will ever again experience such a boom. New buildings between 1940 and 1950 can be counted on one's fingers, but in the decade between 1920 and 1930 some 29 new buildings were added.

The alumni, who have a lot to say about the welfare of Dartmouth, began looking at the mushroom growth and at the figures, and many of them took alarm. The College could not stand the expense. We were headed towards inflation. Debts would kill our academic standards. We were becoming a country club. Former trackmen told one another that the ritzy life in Hanover was breeding undergraduates with legs too thin to run the quarter. Former football men regretted that the luxury was softening the gridiron spirit. Former Phi Beta Kappa men complained that study had become so pleasant as to be insidious and present-day scholarship was sinking to deplorable levels. Most of all, opponents of the Hopkins building boom groaned because of the expense. Everything cost so much. "We can't afford it, they said anxiously. "Let's wait for normal times." They are still waiting.

Now in 1950 nearly everyone agrees that the administration of President Hopkins will go down in Dartmouth history as one of the wisest in building construction. Costs have risen so fantastically that if the Trustees had postponed enlargement, we should be unable in the foreseeable future to give young men the education that they now can have through the libraries, laboratories, classrooms, dormitories, and athletic fields. Spirit or no spirit, Dartmouth would have become a second-rater. Nor can sensible persons maintain that Dartmouth athletes are less rugged than those before 1920. Nearly all the records have been broken over and over again. If the football team of 1920 could be recreated and play this year's, 1920 would probably be slaughtered.

It was with the destruction of the old Dartmouth skyline—Culver, Butterfield, and the White Church, which once dominated the campus—and the creation of the new that Mr. Gooding was vitally concerned, for the 29 new buildings and the remodelled old ones were to become his responsibility.

A graduate visiting Dartmouth in 1930 after ten years' absence would have found the view from the Inn porch almost stunning. He would first see Baker Library erected at a cost of $1,132,000 and listen to the 15 chimes in its tower costing another $40,000. He would be only mildly surprised to know that Mr. George F. Baker had given a second million dollars just for the upkeep of the library.

Walking up North Main Street past the remodelled Tuck, now called McNutt, the graduate would find the Sanborn English House, valued at $344,000, with its luxurious own private library and private offices for the English staff, the envy of most Departments of English in the United States. Just beyond, he would find Carpenter, the art building, $306,000.

Standing on the west steps of Baker, he sees what one great decade has brought forth for Dartmouth in vital growth, the wealth and the power of the new era: Silsby, the natural science building, $467,000, a nice complement to Steele, the chemistry building, another $467,000; the dormitory row with Russell Sage, Gile, Lord, and Streeter, $607,000; and then the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration with its four buildings, $725,000.

The alumnus's walk up North Main Street still gives him views of more buildings built in that fabulous decade: Clement Greenhouse, $47,000; Dick Hall's House, the college infirmary where it is almost a pleasure to be sick, $298,000; the Hilton Field House and Golf Course, $48,000; and the Outing Club House overlooking Occom Pond, $60,000.

A stroll down East Wheelock Street has its sights also: three dormitories, Woodward, Ripley, and Smith, $251,000; the Davis Field House, $138,000; the squash courts, $70,000; and the Davis Hockey Rink, $69,000.

MODERN LIFE, say the optimists, is getting better and better, but not even they can say that it is simpler. "The costs of operations show the increased complexity which we in the Administration Building have to face," Mr. Gooding points out. "In 1916, four years before I went to work for Dartmouth, college expenses were only $432,475. In 1930 they had risen to $1,811,321. In 1949 the total income and expense amounted to $3,345,180. Plant operation and maintenance cost $394,333- In 1916 the faculty numbered only 114; in 1931, 277; in 1950, 330. Salaries for the faculty in 1916 could be taken, care of with a mere $245,000, but it took more than a millioij in 1931, $1,080,416 to be exact. And they are of course going up. In 1949 the figure was $1,753,760. The same is true for officers o£ administration. In 1916 their salaries amounted to only $43,000; in 1931, $146,000; in 1949, $363,274."

Mr. Gooding himself began with a crew of about 100 when he came to Dartmouth; now he has two and a half times as many on his payroll. Good enough on his arrival, the heating plant had to be remodelled with new boilers and new engines. It takes three men for each of its three shifts and with spare men for maintenance requires 12 over a 24-hour period.

"Think of how a Dartmouth student uses electricity," says Mr. Gooding. "He turns on his radio first thing in the morning, keeps it running all day, and studies by it at night. He leaves on all his lights when he goes to class. They burn all day. In the old days I used to turn off electricity all over Dartmouth College when daylight came, but I could not do that now. I don't blame the students; they are doing only what they have been taught. Electric companies ran all sorts of advertisements encouraging the public to burn electricity. And burn it they did, in such quantities that the companies could hardly keep up with the demand. Think of the blaze of electricity in the Baker stacks at night. We are trying to inculcate in professors and students some sense of responsibility about snapping off lights when they are through with them."

Mr. Gooding wages a never-ending battle against the students who persist in using electric toasters and hot plates. But fight it he must for two reasons which some students find invalid: first, the additional power puts too much strain on an already overloaded plant, and, second, cooking and food in the dormitories attract cockroaches, mice, and rats.

"Most students are cooperative," says Mr. Gooding. "I find that prominent athletes, the 8.M.0.C., the leaders of activities all want to do right. The little fellows feeling insecure want to blow up their egos by requesting exceptions or defying the regulations they are the ones who give us the headaches in the Office of Buildings and Grounds."

Mr. Gooding does no actual policing himself. He turns that over to Captain Theodore Gaudreau of the campus police, though Mr. Gooding does have a hand in superintending squads searching during vacations for illicit electrical equipment in dormitories. (Offenders' names are turned over to undergraduate disciplinary committees who impose money fines.) Captain Gaudreau is assisted by Nelson A. Wormwood, the Inspector of Grounds and Buildings, who carries out his duty in a manner which to students seems sensationally grim and omniscient. Mr. Gooding gives them extra policemen for weekends and parties to make sure that order is preserved and that visiting firemen from other colleges don't get out of hand.

The Superintendent of Grounds and Buildings believes that one reason why his department has run so smoothly over these 30 years is that he has had excellent asistants. For seven or eight years at the beginning the College put all the responsibility on him, but his faithful henchman, Doc Wood, a picturesque figure, good on details, relieved him of many minor matters. In 1928 the Trustees appointed as Assistant Superintendent Mauritz Hedlund 'l2, a part-time instructor in mathematics, who died on the job. He was succeeded by the present Assistant Superintendent, Richard W. Olmsted '32, who got his engineering degree in the following year and his business training as an Assistant Warehouse Superintendent of the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company. Three women have also been mainstays in the office: Miss Helen Brown, who served under three Superintendents (Mr. Hunter and Mr. Wells before Mr. Gooding) and died about 13 years ago; Miss Myrtle E. Stewart, who has been in the office for some 25 years and knows the ropes; and Miss Aloyse Duffy who was transferred to the office several years ago from the Treasurer's office.

Miss Stewart and Miss Duffy know what to say to the professor who has broken a light bulb in a college apartment and would like to have a new one free please and to another professor who wants to know whether he can buy pencils for himself at a discount, cheaper than he could at Dave Storrs'.

If Mr. Gooding had luck in inheriting reliable men and women, he has had talent in developing them. The elms, which are one of the glories of Hanover, might not be what they are without the constant and expert work of Gordon Cloud. He could get a job anywhere at much more pay, but he remains faithful to his boss and the College. Steve Sokolowsky, the Pole, has evoked admiration from many spectators as they watch him grading lawns so meticulously and fitting sods in place with such skilled and happy hands. Mr. W. H. Moore, the retired engineer, though he often disagreed healthily with Mr. Gooding, says that no one could have a better man to work for. The proof is that the turnover in men is small: the average is 13 or 14 years on the job.

THE BUSINESS of superintending a plant worth more than $11,000,000 may make a man seem like a public figure always on the go in the administration building, gymnasium, laboratories, dormitories, and heating plant. But Mr. Gooding is about as private a public figure as there is in Hanover. When not superintending, he centers his life about his home on North Balch Street, which has always been known to the Gooding friends as a pleasant place to visit.

He is fond of fishing for trout, not brook trout, but lake, and one of his favorite spots is Averill Lake. Every Wednesday evening he is to be found at the Hanover Inn where he is rated among the top players in duplicate contract among such experts as Mary Gile (wife of Archie 'l7), Mrs. John M. Mecklin (wife of the Professor Emeritus and mother of John '39, the CBS Canadian news broadcaster), Prof. Harold E. Washburn 'lO, Prof. Robin Robinson '24 and Prof. Michael E. Choukas '27. His third passion is indolence in a Maine cottage near Portland, the city where he and Mrs. Gooding were born and brought up. Anywhere in Casco Bay is perfect.

The three Gooding daughters all married Dartmouth graduates (John D. Detlefsen '37, Donald F. Pease '37 and Robert S. Hyde '44) and with the help of their brother John '45 have made their father five times a grandfather. All have moved away, but the family home at intervals cannot be said to be without young blood.

John, a fair football player, a good skier, and an excellent tennis player, formerly No. 1 on the varsity and at present a professional during the summer time in Maine, is most often a Hanover visitor. He has been teaching History and English at Mt. Hermon School and is taking the coming year off to work for his M.A.

Mr. Gooding has always been keenly interested in John's athletic career, and used to surprise him with a stroke by stroke, game by game and set by set analysis of a tennis match. But while other Hanover fathers turned out daily to watch their sons in football or tennis, Mr. Gooding used to be conspicuous by his unqualified absence. An indication of his devotion to duty is that though few officers were more justified than he in leaving their offices and moving about the grounds and buildings, Mr. Gooding worked by choice in places well away from the court. It is of course an exaggeration to say that he never went to see John compete. It may be a coincidence that when John was playing well against his biggest rivals in the final rounds .of tourna- ments, pressing business near the gymnasium required Mr. Gooding's presence. On his face when the match ran close could be seen an expression less relaxed and less analytical than usual.

At that moment, the world of reducing valves and duostats, air pressures and air infiltrations, trap failure and radiation hammering were as far away as coldblooded personnel who use their gooseflesh as the excuse to insert hairpins and pencils into thermostats to improve their operation and the efficiency of the Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds.

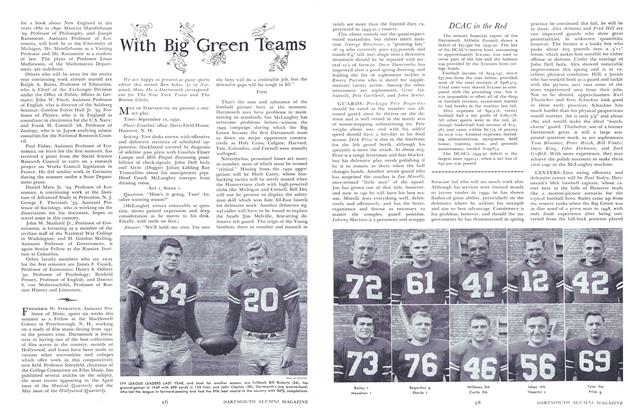

THERE'S ALWAYS PAINTING TO BE DONE: Mr. Gooding, Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds, checks over an assignment sheet with Ora Grant, paint foreman, who joined the staff just 40 years ago.

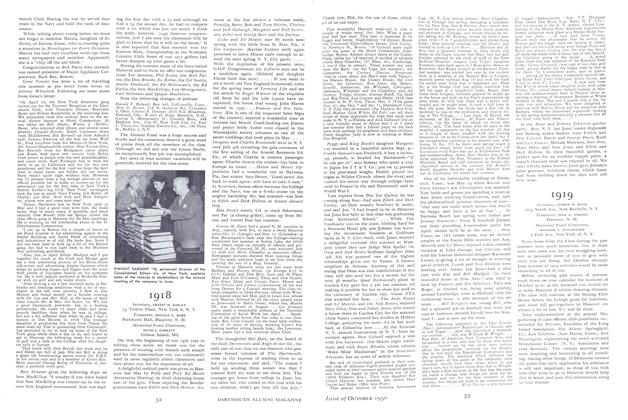

AT THE HEATING PLANT, nerve center of Dartmouth's plant operations and home of the fire whistle, Mr. Gooding talks with Al Waterman (center), chief engineer, and Bert Sargent, his assistant.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFINIS

October 1950 By Bernard G. Sykes '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, JULIUS A. RIPPEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

October 1950 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Article

ArticleTHERE'S METHOD Behind the Fall Madness

October 1950 By ROGER K. WOLBARST '43 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

October 1950 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR.

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

November 1951 By John Hurd '21 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE CARIBBEAN.

January 1960 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksUNDER THE ROCK, POEMS FROM A VALLEY.

JANUARY 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksHOW TO LIVE LIKE A RETIRED MILLIONAIRE ON LESS THAN $250 A MONTH.

November 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksOFF THE SAUCE.

NOVEMBER 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBIG BUSINESS – YOUR LIFE WITHIN IT.

October 1974 By JOHN HURD '21

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY ACTIVITIES

January 1917 -

Article

Article"Amen, Etc."

June 1924 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR MCWHOOD GOES TO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

August, 1926 -

Article

ArticleMidical School

March 1943 -

Article

Article"Possibly the Finest"

June 1954 -

Article

ArticleTHE AMOS TUCK SCHOOL OF ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE

August, 1912 By Wiliam R. Gray