It may not be amiss thus early in the academic year to restate what the MAGAZINE conceives to be its function. There has been more or less discussion in the past few months as to the feasibility of changing the character of this publication as well as its frequency of appearance; and therefore it seems to be a just occasion for considering the proper place of an ALUMNI MAGAZINE in the scheme of things collegiate, with a view to discovering what system best serves the end in view. As the present editors see it, everything depends upon what the end in view may be.

In the estimation of the present editors, the MAGAZINE exists chiefly in the hope of linking up to the actual college the scattered bodies of alumni, by keeping them reasonably well informed as to what the college in Hanover is doing and hopefully by renewing at regular intervals their own sense of an actual connection. It has been remarked many times in these columns that it is possible to take a too narrow view of what a college is—by assuming it to be composed only of the few hundred men in actual residence at any one time, either as students or officers of instruction. It is felt that this is a distinctly incomplete picture and that the essential thing to promote completeness is the awakening of a sense of abiding union with the college on the part of such as are no longer on the ground. For the purpose of thus linking up the alumni to the resident part of the college the MAGAZINE proposes to exert its best endeavor.

The suggestion that the frequency of publication be changed to the weekly form, rather than monthly, has been thoughtfully canvassed by those most intimately acquainted with the problems involved. It is true the weekly form of alumni publication is already in vogue in many other institutions—chiefly the larger universities. But it has seemed thus far to be an undertaking so beset by difficulties and handicaps as to render this experiment an unwise one to make at Hanover, if the function above referred to is to be satisfactorily performed.

The cost of a weekly publication would be so great as to entail a somewhat enhanced price to the readers, which would in itself be a serious handicap—tending to defeat the purpose for which the MAGAZINE is published by curtailing its circulation. Some small gain would be accomplished for those who continued to be its subscribers by affording them more prompt news of college events, chiefly in lines of sport. But it is feared the evils would rather more than offset the benefits, since the first and great commandment in any such case is to get the maximum of readers and thus make the effect on the alumni body as nearly universal in its reach as circumstances allow. There is some doubt whether a publication appearing so often would be welcomed—i. e., whether the potency of such a weekly magazine to interest its readers could be sufficiently sustained. Thus far the arguments appeal to the conductors of the MAGAZINE as strongly favoring its present estate as a monthly issued nine times a year, although it is quite probable that changes in the scope of its various departments are to be deemed desirable.

Editors seeking to "mould public opinion" as the phrase goes are fully aware of the limitations of their power in this direction. No one with much first-hand experience holds many delusions of the power of the press, so much extolled in song and story. There is little to suggest the mock heroics of Pott and Slurk in the editorial profession of the present day. One knows that public opinion has a tendency to mould editorial judgment almost as often as it happens the other way about. Nevertheless the process continues, with varying success and. with occasional instances which are rather disheartening to those who do the preaching; and it is with the wish to extend as widely as may be the bounds of its congregation that the MAGAZINE prefers any policy likely to keep the number of its readers at the maximum. A publication which appeared three or four times as often and was read by half the present number of subscribers would but ill serve the need.

Nothing can force success in such a field. It has to grow naturally. If this MAGAZINE is to be of genuine efficiency in its attempt to weld the alumni into a recognized integral part of the collegein-being, it must do it by dint of making itself both valuable and interesting to such as read it—in which case it is likely to be more and more widely availed of by graduates of the college. The difficulty is to enlist the interest of those not accustomed to think of themselves as still a vital part of the college—and then retain that interest. Too many treat the college as a place to which to repair at five-year intervals for the purpose of a class reunion. Not the least of the MAGAZINE'S aims and desires is to quicken the realization of a permanent and continuing status.

This does not presuppose that any considerable number of graduates can be induced to take that intense personal interest that is manifested by the exceptional few—sometimes referred to as "professional alumni"-to wit, those who make of the college an obsession almost amounting to a religion. But it is hoped, and probably with reasonableness enough, that by a not too persistent effort the great body may be led to take somewhat more seriously than would otherwise be the case the duties and privileges inhering in the college fellowship. To that end whatever is pertinent is worthy of being tried. The main thing is to arouse intelligent interest in what the college is doing and if possible secure from widely dispersed members of this ancient Dartmouth family expressions of opinions, such as vitally interested sons will be sure to feel, concerning the further development of a noble and aspiring institution of learning. To this college we all belong. From it there is no decree of divorcement. The main thing is to make it plain that membership did not terminate when the coveted sheepskin was handed to the graduating class, but became full and complete.

Casual conversations with men from any college alumni body will probably convince any reader of this MAGAZINE that the disposition is growing to demand a genuine housecleaning in the matter of professional athletics. It seems to be recognized more and more widely that, while the raw forms of professionalism which were common a quarter of a century ago have almost disappeared, and while the average college is creditably exacting in certain obvious matters of amateur standing, there remains a very common form of professionalism which is less obvious, but distressingly common —and, what is more, increasingly distrusted by thoughtful and sincere men.

By this is intended the custom of insuring by financial aid the choice of a particular college by young men whose athletic prowess has been conspicuously demonstrated in fitting schools, either public or private. It is possibly a stretch of the term "professionalism" to apply it to such cases; but the essentials of professionalism are there and they are not entirely occulted by the fact that the student, once he decides which college he will select on these terms, is to all outward seeming a bona fide student. He attends lectures and classes, pursues his appointed course, ultimately graduates. He is not, so far as appearances go, a hired player. But the fact remains that the enthusiastic philanthropists who raised the money for his education were induced thereto by the fact that, while he was in prep school, this man showed unusual ability as a ground-gainer, or drop-kicker, or pitcher on the baseball nine. Their actual idea was not to assist a worthy young man to obtain an education, but to bolster the college team.

In such cases there is usually some little local rivalry among the various alumni clubs of clivers colleges. The incentive in each instance is the same—to bolster the college team. One tries to persuade oneself that this is not really professionalism by harping loudly on the philanthropic aspects of it; but we doubt that in their heart of hearts many men are really convinced by their own reasoning. The proof of it is to be found, as was remarked at starting, in the fact that more and more thoughtful on-lookers are heard to demand that there be a wholesale and honest housecleaning, designed to prevent this indirect hiring of players to go to College A rather than College X.

The MAGAZINE would by no means de- plore the desire to have one's college represented in sports by teams capable of success. This desire is natural and right, so long as it is not made the chief end and aim of college existence. The trouble is that so many of us, consciously or otherwise, come to measure the stand- ing of any institution of learning by its prowess on diamond, or gridiron, and devote rather more energy than either the case requires or propriety justifies to recruiting the student body with young men who will shine on the athletic fields, whatever else they may do.

No one wishes to go the length of penalizing the athletic gift by making this talent preclude the possibility of receiving aid in pursuing the higher education. There's little danger of that. What one deplores is the frantic bidding which often takes place in the case of a desirable young athlete to induce him to go to one college or another for the sake of his brawn alone. One knows the resentment certain to be felt by little groups of athletic enthusiasts—there are such in every alumni body—when efforts of this nature to promote the athletic interest by a seemingly innocent method are called in question. But one finds that the innocence of the method is being widely doubted, just the same; and it is apparently high time something were done by all colleges to ascertain the extent to which this practice prevails. In a way it is hiring men to come to one college when, in the absence of such financial inducement, they would probably go to some other. From what we hear it is not a rash statement that in this respect practically all prominent colleges have at some time been tarred with the same brush. It isn't the crude thing that George Ade once held up to ridicule in "The College Widow"—the deliberate hiring of an imitation student, who elected "fine arts" and "aesthetics" as a cloak to give respectability to his presence on the team. That is universally detested and condemned. Whatever pro- fessionalism is common now is the indirect kind, of which mention is made here. It doesn't look terribly alarming. It can be dressed up to look rather well. But is it really quite the creditable thing?

The close of a football season unusually chequered in its character leaves one rather bewildered. The most obvious comment is that to wind up the year's play with a victory which was quite generally unexpected leaves a very good taste in the mouth—more particularly as the victory was won against a determined foe, who had previously triumphed over teams that had defeated our own. To beat Brown by a score of 7 to 0, after Brown had beaten Harvard by a score of 3 to 0—and after Harvard in her turn had beaten Dartmouth by a score of 12 to 3—certainly offers compensations. In the matter of scores the season might have been a more resplendent success—but it might easily have been much less so. The judgment of the MAGAZINE is that the football record of the 1922 season is a thorough credit, both to the College and its team, as well as to its chief coach. There were games that we didn't win and hardly looked to win. There was at least one game lost that no one had expected to lose. The Waterloo of last year's Cornell game was not duplicated in the clash of this season—though the margin of defeat remained too wide for comfortable reflection. But the restoration of the game with Harvard, highly gratifying in itself, led to a most admirable exhibition of football and to the revelation that Dartmouth, even in mid-season, was no mean adversary for the highly skilled Crimson team; and the closing game in Boston with Brown measured up to the best traditions of a game in which Dartmouth has always claimed to excel. For a season marked by such thoroughly sports-manlike'and increasingly skilful playing we may be truly thankful.

As the MAGAZINE goes to press news comes of the death on December 11 of General Frank S. Streeter at his home in Concord, New Hampshire.

Few individual alumni of Dartmouth have ever been more widely known or more sincerely esteemed. His more than 30 years of continuous service as a trustee of the College, his abundant activity in alumni matters, his unfailing personal interest and unstinted generosity, coupled with extraordinary gifts of a social and professional character, marked him out as among the most eminent of recent leaders in Dartmouth affairs. At the completion of his 30th year as a trustee mention was made in these columns of his unusual services and of their vital importance in the up-building of the new Dartmouth of which we are all so proud. It was little understood at that time that Gen. Streeter's days on earth were so straitly numbered, although with the lapse of the year it became evident that his illness had taken a hopeless turn and that the end could not be far away. It remains to reiterate, with profound conviction, the opinion that Dartmouth never had a truer, more constant, more helpful son than he; and to express the gratitude we all must feel for the fact that so much that was true and constant and helpful was vouchsafed to us through so many and such fruitful years. The number of men who have contributed to the creation of the present estate of the College is great and the services of many have been notable; but none surpassed General Streeter in tireless enthusiasm, or in direct and generous material and moral aid in carrying forward the tasks to which the College had set its hand. Though much is taken much abides. There remains, and will always remain, the inspiration of this man's example, fostering the emulation of his usefulness —not in feverish or sporadic outbursts, but sustained throughout a generation or more of constant association.

To those not on the ground, to whom the precarious bodily condition of Dean (emeritus) Charles F. Emerson was not known, the announcement of his death December 1 came as a shock. Even his associates at Hanover had hardly expected so abrupt an ending to his long and useful life, although the end was obviously not long to be postponed. Naturally the loss of this long-time servant of the College comes closest home to those who were under his instruction, or his care as dean, during his active life. It is curiously difficult for such to realize that, to something like half the present members of the Dartmouth fellowship, Dean Emerson was known chiefly as a familiar figure on the streets of Hanover, and not as an active member of the college staff. Such, however, is the fact. It is nearly ten years since he ceased to be active dean of the college ; and, counting both present students and alumni, it is probable that the dividing line between the older and younger halves now falls at just about that point in our elapsed history.

Professor Emerson's connection with Dartmouth began on the day when as a freshman he matriculated with the class of 1868—to wit, in the autumn of 1864. That connection ceased only with his death. To very few men is there vouchsafed such a continuity of collegiate activity. To very few is vouchsafed a similar place in the affectionate remembrance of such a host of men. Born in Chelmsford, Mass., in 1843, Dean Emerson came as a youth to Hanover and there remained throughout his days, loved and honored by all who knew him through the nearly 60 years of his constant and vital association with the College and the neighborhood. In his student days he was an athlete of sufficient prowess to win for himself the post of associate instructor in gymnastics—so that his career as an officer of instruction antedates even his baccalaureate degree. He continued to serve in the department of gymnastics until 1870; but to this activity he added immediately after graduating the duties of a tutor in mathematics—a position which he filled until 1872. In the latter year he became associate professor of natural philosophy and mathematics (1872-1878), with further responsibilities in the department of astronomy, in which he was appointed instructor in 1877, retaining this duty until 1892. The Appleton professorship of natural philosophy was taken over by him in 1878 and retained until 1893, at which time his post became known as the Appleton professorship of physics. His active teaching career ended in 1899; but the duties of the dean, which he assumed first in 1893 and which continued to grow in importance as the College expanded, remained in his hands until his retirement in 1913. Prior to the appointment of Dean Emerson, the duties of the dean had been exercised by the president—a possibility while the College was an intimate little body of some 400 men, but manifestly an impossibility when the sudden growth under Dr. Tucker's presidency began. To Professor Emerson, then, belonged the honor of being the first Dartmouth dean; and right worthily did he fulfill this mission, for which his understanding of youth and his ready sympathy therewith so adequately equipped him.

Subsequently to his retirement, Dean Emerson continued to reside in town. It is inconceivable that he could have been happy anywhere else. His lifelong association with the College and his intimacies with both college folk and townspeople clearly dictated his retention of a home in Hanover, where he was so cordially esteemed. By both town and college he is sincerely mourned.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

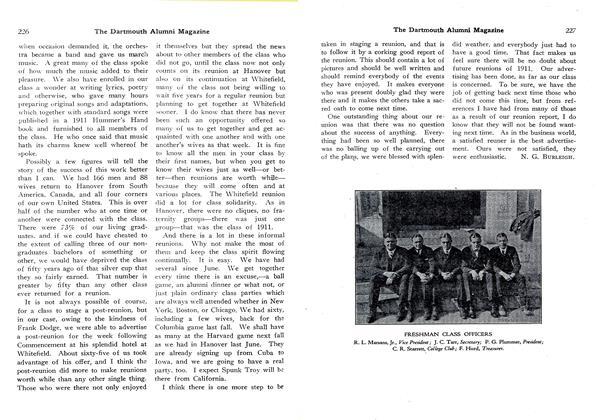

ArticleTHE IDEAL REUNION

January 1923 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH '11 -

Article

ArticleVERMONT'S LAND GRANT TO THE COLLEGE*

January 1923 By ROY BRACKETT '06 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI COUNCIL MEETS IN NEW YORK

January 1923 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

January 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

January 1923 By Whitney H. Eastman -

Books

BooksPUBLICATIONS

January 1923 By J.M.P.

Article

-

Article

ArticleEDUCATIONAL POLICY HEAD INVESTIGATES IN EUROPE

May, 1924 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

October 1939 -

Article

ArticleAlumni in State Service Meet

June 1951 -

Article

ArticleFootball

November 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleATHENE

April, 1915 By Francis Lane Child '06 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22