The results of the first semester of the new selective process have been analyzed by the Director of Admissions, E. GORDON BILL. His conclusions follow:

The various alumni groups have been so intensely interested in the attempt of the College to contribute something to the educational development of the period by the inauguration of the selective plan for admission that I felt it would be in order to diagnose for their benefit certain sympto,ms which have shown themselves in the first child of this process, Of course at this early stage I can write only of distinctly intangible and perhaps evanescent symptoms.

First of all, thirty Freshmen were separated from college as a result of failing three or more courses. This number constitutes 5.5% of the class as compared with thirty-two Freshmen, or 5.3% of the class separated at a corresponding time last year. Any hasty conclusions on this result will certainly be erroneous as many rather illusory factors must be taken into account. For example it should be noted that the number of Freshmen separated at the end of the first semester last year was very much smaller than that of any previous year; a delightful condition that was, however, nearly reduced to "normalcy" at the end of the second semester and completely so by the end of the first semester of sophomore year just passed. Further, it is of some importance in the matter under consideration to observe that it has been common talk on the campus and in the forum that, for one reason or another, the interruptions of curriculum work have been unduly frequent within the college during this past semester, and particularly detrimental to men who had not formed habits of concentration; a rumor that is now verified by the fact that twenty-nine Sophomores have just been separated from college and fifty-three put on probation, and further by the fact that disciplinary action was just taken in.

However, even if the number of Freshmen separated this month had not been less than that in preceding years, it would be very superficial and illogical to conclude that the selective process had failed in its first test. Under this selective scheme every single boy who had made a first-class scholarship record in school was selected for admission. Obviously, under the old "first-come-firstserved" method the number of men in . the class qualified to do good scholastic work could not possibly have been as great as it actually turned out to be. As a matter of fact, 64% of this year's class passed all five courses, as compared with 65% of last year's class—a very exceptionally high percentage—but only 3.8% of the class of 1926 ranked 3.0 or better, as compared with 8.7% of the class of 1925; but, in my estimation it would be absurd to attribute this inferior record in high scholarship grades to the selective process, which took all the good scholars who applied, rather than to those intangible conditions in the complicated life of the College, which last semester impaired the scholastic rank of men throughout the entire institution.

On the other hand, it strikes me as superficial to assume as final proof of the value of the selective process the opinion held on the campus and by the coaches that the class contains many more good athletes than usual in firstclass scholastic standing; an opinion that is upheld by the fact that all freshman athletic teams have not only been especially successful this year but have had practically none of their members disqualified by poor scholastic standing. Nor should we accept as final proof of virtue in the selective process the fact that the class is chuck full of an exceptional amount of particularly strong fraternity material. A selective process such as ours is bound to get a large number of well qualified athletes and also of personable boys whom one likes to have as friends. As a striking example of this last fact I need only say that whereas I am in general delighted at mid years to see the College rid of the Freshmen who are separated, I was this year distinctly sorry to see at least twenty-five of the thirty separated sever their present connection with the College. In other words, even these boys were possessed of character and personality and charm.

But if none of these things were true the selective process could not possibly be condemned until after several years' trial, and after certain obvious weaknesses had been strengthened. The real test of our system of selection partially lies in the percentage of the class that will graduate with credit to themselves and to the College in June, 1926. It should not be forgotten that one of the great tragedies of the College is that each year each junior class enrolls over 20% less than it did at the beginning of sophomore year, and even the present splendid senior class, which will graduate about four hundred men, entered with no less than six hundred and ninety-eight. The test, therefore, is not in how many show up as unqualified in their first semester, but in what percentage of them are possessed of the ability, ambition and industry to graduate with their class. Above all, however, the real test lies in the class's capacity for development and growth. To use a hackneyed expression, it lies in the potentiality of power possessed by the class. Will the growth of this first child of the selective process, nourished by four years in Dartmouth College, be such that at graduation it will be rated a great class, as one possessed of real captains and thoroughly steady, reliable henchmen, as one which the alumni and faculty and administration will see graduate with es- pecial confidence?

The geographical distribution of the thirty failures mentioned above has points of interest. Three of these were drop-backs from other classes and had no relation to the selective process. Of the other twenty-seven, New York State sent ten; states west of the Mississippi, six; southern states (when it is thirty below in Hanover we call Delaware a southern state,) three; Mississippi, two; New Jersey, two; Ohio, two; Pennsylvania, one; Rhode Island, one. Especially noteworthy is the fact that no one was separated from Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, New Hampshire or Vermont, although each of these states sent large delegations. Moreover, no one was separated from the entire "north country" as all the boys from Canada also came through in fine shape. Contrary to the unenlightened criticism of certain sections of the academic world which have laughed at that element of the selective process which selects all sons of Dartmouth alumni and college officers who are qualified for entrance, not a single son of an alumnus failed.

Two failures from Massachusetts out of a delegation of one hundred and forty-two men from that state, in other words only 1.4%, is a remarkably fine showing. I am too much of a mathematician to be too greatly disturbed by the fact that of the eighteen men separated who did not enter by any group preference of the selective process, no less than ten came from New York State, these failures constituting 10% of the New York State delegation.

As most of us would pass into decline if we did not have sympathy, I think you will be glad to know in conclusion of a few of the difficulties besetting any sympathetic operation of any selective process. To start off with, it is clear, as the President has said, although we can hope to measure a boy's ability to do college work we cannot measure with any hope of accuracy his willingness to do college work after he gets here. So long as the material on which we work is such a complicated and delicately adjusted organism as an adolescent boy, we will always expect to wake up in February with many of our dreams proved nightmares. For example, one boy who failed three courses last semester came from one of our choicest secondary schools from which he graduated in the highest quarter of his class, and in which he had been class president for all four years by virtue of ability, personality, executive capacity, and reliability. It turns out that he has been near a nervous breakdown as a result of an old mastoid trouble and a severely taxing employment without rest, last summer. When he gets his health cleaned up we are going to give him another chance, and we are not at all sure that his failure is an indictment of the selective process. Four failures were selected either because they had excellent brothers entering at the same time, or had brothers already in college. Only one of this group would have been selected on his merits, and he is just beginning to get back to normal after considerable illness last year. I believe that any selective process so cold and deadly as to fail to take stock in the vital family interests aroused in having two boys together in college should be operated as a parimutuel machine.

One man who flunked out had graduated from normal school and had been a successful teacher and school administrator. Although his scholarship at school had been dangerously low for successful college work, his maturity, experience and exceptionally high personal ratings by principal and alumni made him an eminently desirable risk. Two failures were very highly rated by schools whose judgments we cannot again accept, as well as by alumni. Two others were fine students and highly rated by good schools. Incidentally, they were first-class athletes. However, their popularity here simply could not permit them to make use of our limited library facilities.

Three failures had not been very strong scholastically at school, but they were highly rated by alumni, had been prominent in school activities, and were the oldest boys of parents who had become enormously enthused over the prospects of their boys having advantages they had lacked. One failure was a son of foreign born parents. His scholarship record was rather poor but his personal ratings seemed to offer the college a fine opportunity to be of service with at least an even chance of success. Two others were good athletes with strong personal ratings from both principal and alumni. Another had been a rather poor student, but faithful, and possessed of exceptional character. Even though separated I wish to prohesy he will in years to come be thought of affectionately as a loyal Dartmouth man. Finally, two of the failures were selected apparently when the Director of Admissions was dreaming of being back teaching Mathematics, and selecting particular solution of differential equations. These two boys do not seem to have had much logical claim for selection except that they had been rather severely bitten by the school activity mania.

Nothing that has emanated from Dartmouth College in the Dartmouth lifetime of the writer has, I believe, made such a profound impression on the educational life of the country as has the inauguration of the selective process. Although at present it is simply a creaky old model, I believe it is destined to become a vehicle of great power and beauty and service not only to Dartmouth, but to education in general.

A view of the gallery which watched the carnival events on the golf links

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIt appears from a recent balloting

April 1923 -

Article

ArticleAN ALUMNUS ON THE OUTING TRAIL

April 1923 By ALBION B. WILSON '95 -

Article

ArticleMEMBERS OF COLLEGE GET HIGH SCHOLARSHIP RECORDS

April 1923 -

Article

ArticleINDIVIDUAL RECORDS OF PHI BETA KAPPA SENIORS

April 1923 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

April 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleGLEE CLUB WINS INTERCOLLEGIATE CONTEST

April 1923

Article

-

Article

ArticleHe who has followed the daily press

December, 1909 -

Article

ArticleRegional Scholarships

MARCH 1930 -

Article

ArticleAdmissions Assistant

February 1956 -

Article

ArticleHopkins Center Opening

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT

January, 1912 By Prescott Orde Skinner -

Article

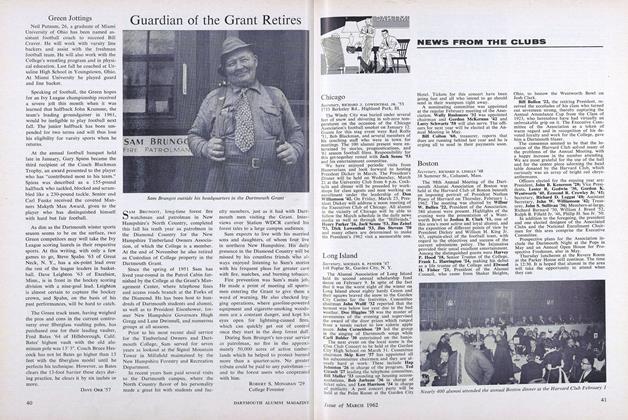

ArticleGuardian of the Grant Retires

March 1962 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29