Divining futures that may not be so divine.

THE FUTURE has long been a notion met with much heel-digging and disbelief. Take, for instance, the 1895 statement by the president of the Royal Society: "Heavier-than-air flying machines are impossible." Or the announcement by the chairman of IBM in 1943. "I think there is a world market for maybe five computers." Or the fact that in 1962 Decca Recording Cos. rejected the Beatles saying, "We don't like their sound, and guitar music is on the way out."

The point, according to English professor Judy Worman who presents these and other quotes on the first day of her "Prediction Fiction" seminar, is that we need to be open-minded about what's to come. "Nurture your mind with great thoughts," said Benjamin Disraeli, "for you will never go any higher than you think."

The heights of thinking that Worman wants her first-year students to reach concern the bizarre possibilities that the next century may bring us—anything from George Orwell's Big Brother vision from 1984 to James Redfield's spiritual connectedness to The Clelestine Prophecy. "Be prepared," Worman challenges students, "to expand your mind and change your way of thinking about the future."

The idea for the "Prediction Fiction" course began for Worman as an experiment. With technology advancing so quickly and the millennium rapping on the door, she wanted to follow chronologically the kinds of Utopias—positive and negative-that have been presented in fiction since the turn of the last century. What she found when she opened the lid of literature was a slap in the face. Authors have been warning us all along about what can go wrong. In Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid'smaid's Tale women are used as sperm receptacles in Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 firemen start fires in order to burn all books, and in Lowry's The Giver the world has been wrung of all color and emotion, leaving a dull gray of sameness. Still, in all these negative Utopias there is hope for escape, for an underground world of freedom and possibility, "It occurred to me that we are basically a hopeful society," said Worman. "We tend to believe that at one time society was perfect, that we have gotten away from it and are trying to get back to the 'Garden of Eden,' whatever that may mean."

Since as far back as Plato's Republic, Utopias have offered us ways to conceive of new worlds. In the sixteenth century, Sir Thomas More titled his work "Utopia," which critics now speculate was a play on the Greek word meaning "nowhere" or "no place," instead of the Greek word eutopia meaning "good place." Whether or not it is "no place" or "good place," Utopias since More's have been divided into three eras by historian Frank E. Manuel. He labeled the first period, from More to the French Revolution, as an era of calm felicity. The next period, the nineteenth century, he split into dynamic socialists and other historically determinist Utopias. Utopias of the third period, our own twentieth century, consist largely of psychological and philosophical sophical Utopias.

In choosing books from that last period, Worman pulled from all perspectives- from Edward Bellamy's socialist view to Margaret Atwood's feminist political vision to Aldous Huxley's tale of genetic horror. The idea of an all-controlling society that forces people not to think for themselves seems to run as a steady marker through all these books, says Worman "Technology is speeding up so quickly in the twentieth century, with things merging so fast, that writers have more or less been looking negatively at what life is going to be like."

In this age of advanced communication, it's ironic that we are more isolated than ever. "I'm teaching students who are 17 and 18," says Worman "They've been learning computers from the day they can say 'Mama,' and soon they'll be able to go to college via the computer by watching a professor on a monitor. You can shop that way, too, have groceries delivered, clothing delivered and never leave home. It's scary because one of the things that comes out of the class and these books is that human beings need human beings and a sense of community. When you start isolating people in cubbyholes and closets with computers, disintegration occurs."

Another warning flag raised in the literarure is the idea that inventions meant to free us as individuals are the same ones that can steal our privacy. In The Handmaid'sTale, for instance, the protagonist's freedom begins to slip when she tries to buy cigarettes and finds her centralized account has been taken over by the commanders, so that she can't even buy a bus ticket out.

"The whole notion of technology and the information highway is a double bind," says Worman "Every time you make a purchase your whole life is carded. It doesn't really free you if all your moves can be tracked. If the government has access to that information, it's scary because your privacy becomes less and less and less."

To learn what it is about Utopian societies that fails, Worman and her most recent class examined the literature and found that society thrives on difference. "They seemed to come up with the notion that we are all individualistic and can't be put in the same square or circle," said Worman "We must take the 'bad' with the 'good' and learn by our mistakes."

We can start to do that, Worman believes by becoming educated, by guarding against "doublespeak," and by staying aware of technological changes and in touch with humanity. "You can't be a Pollyanna and say, 'Well, if I don't see it, it's not there. What these authors are trying to do is to force readers to look at the future in more than one way. Advances that are meant for the overall good can become horrors if we lose our human values."

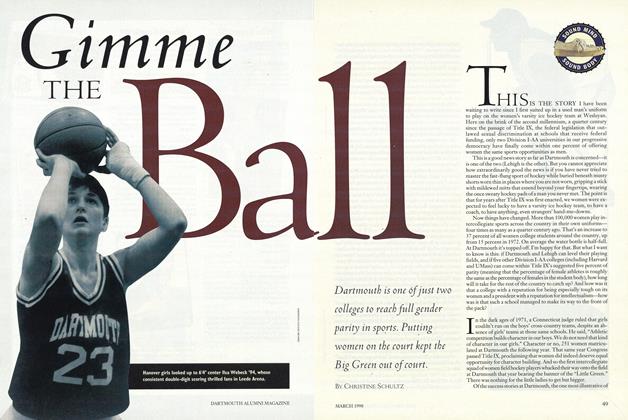

CHRISTINE SHULTZ reported on a quarter-centuryof Title IX for last March's special issueon athletics.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryTo die loving life

December 1998 By Diana Golden Brosnihan '84 -

Feature

FeatureHere by the Fire

December 1998 By James Zug '91 -

Feature

FeaturePost What?

December 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

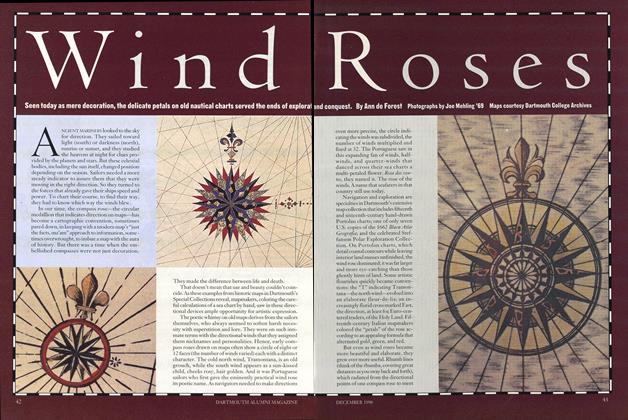

FeatureWind Roses

December 1998 By Ann de Forest -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

December 1998 By Abby Klingbeil -

Article

ArticleLooking for Frost

December 1998 By Noel Perrin

Christine Schultz

Article

-

Article

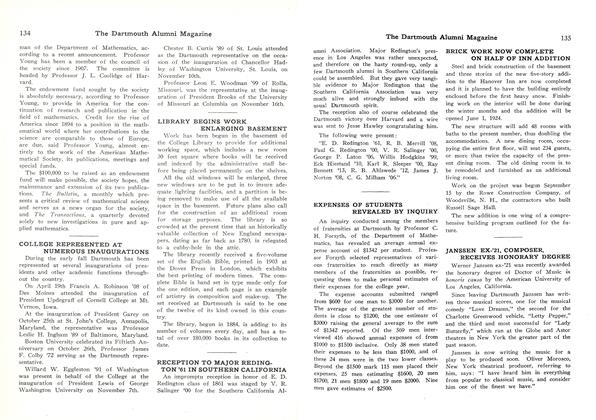

ArticleCOLLEGE REPRESENTED AT NUMEROUS INAUGURATIONS

December, 1923 -

Article

ArticleProf. Patterson Honored

April 1931 -

Article

ArticleGrant Standbrook Named Varsity Hockey Coach

MAY 1970 -

Article

ArticleParkhurst Renovated

June 1951 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Two Libraries

MARCH 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1978 By William Howard Taft