The following communication was sent by a Dartmouth graduate of 1912 to a friend who was enquiring about the advantages of Dartmouth College for his son. It seems to the editors such an admirable document that it is reprinted in this department.

Boston, Mass., February 4, 1923.

Dear Mr.-----:

(1) You ask me why I would send a son of mine to Dartmouth College. In the confines of a letter I may only suggest a few of the reasons. And in doing so I shall try to use my recollections as a Dartmouth man and the son of a Dartmouth man purely as a source of information, rather than inspiration.

(2) Perhaps it would sum the whole thing up to say that, regardless of the enthusiasms and filial feelings which Dartmouth inspires in anyone who lives in Hanover four years, the surpassing desire to have a son enjoy the fullest and most valuable collegiate experience available would make me strive above all things to make HIM select Dartmouth for himself. Then I'd quit worrying for four years.

(3) Traditionally, there is something fine about Dartmouth which inspires one of the lesser loves that rank among the few great affections which stir men deeply during life. "College spirit" is a sort of flippant phrase. It smacks of immaturity and lightsome exuberance. But the bond that Dartmouth seals upon student and graduate is recognized among other college men as something mysteriously different. For this reason it is not to be taken lightly. It seems to me that in the aggregate his "all-for-one-and-one-for-all" spirit is the outward evidence of something which Dartmouth has given to each man secretly and within himself—which he values highly and appreciates instinctively.

(4) Geographically, Dartmouth is fortunate. This is not a matter merely of clean, clear "mountain air" climate, rugged hills, the Connecticut river, and picturesque New England countryside. Nor is Dartmouth to be considered a hermitage isolated from the follies and temptations that surround the city college. A real man handles those things for himself wherever he may go to school. Dartmouth wears her so-called isolation like a jeweled crown. The Outing Club, the original winter sports organization and pioneer in the now familiar pastimes of colleges and society in general, and the Winter Carnival are too well known to mention. The real virtue, as I see it, that grows out of Dartmouth's place on the map, flourishes all the year 'round. The college dominates the town. It is the town. Practically everyone in town is dependent on or a part of the college. There is almost a complete absence of "ready-made" pay-as-you-enter-and-check-your-brains-in-the-lobby amusement and entertainment. Yet they have something for every man in college to do and every man has an opportunity to learn how to play, how to organize his interests, and how to build a hobby-horse that will carry him far and divert his mind during many a busy year that follows.

The result is that there is a complete round of entertainment from movies and athletic events to faculty soirees, teas, dances, dramatic events, concerts and popular lectures; a half a hundred specialized non-athletic organizations, various types of publications to be edited, read, and unrelentingly panned, many offices, honors, and minor distinctions to be sought for and gained — and men — 2000 men from every part of the country to compete with, to talk with, to sit in the crowd with, or play on the stage with, to vote for, to bump into day after day, to live with, to argue with, and to get along with — all around one little square of campus criss-crossed with many paths, all of which meet many other paths. That's what makes a Dartmouth man go to classes and return home with something that was never caught between the covers of a book. That's what gives a boy from Boston a chance to go to college and graduate more as an American citizen than as a Bostonian or a New Englander.

(5) Academically,, Dartmouth has a fine curriculum arranged to give broad scope to personal preferences and specialized abilities yet requiring, especially in the first two years, the science man to take several of the cultural courses and the "arts" man to take a few basic scraps of science. The gymnasium is the largest in the country and one of the most modern from the tank to the flying rings but their scientific laboratories are more modern. The faculty is good. There are some instructors too young to seem benign and wise and there are the usual few who are too wise and old to remember their youth — yet I know of no college where the extra-curriculum contacts between faculty and student-body are so tinged with camaraderie and man-to-man fellowship, discussion, and mutual benefits.

(6) The fraternity has never been an evil at Dartmouth. About fifty per cent of the men are fraternity men. No stigma attaches to one who is not. Only fifteen men may live in a fraternity house and no meals are served in these houses. There is constant inter-visiting, constant rivalry between inter-fraternity teams, and constant competition to keep fraternity scholarship averages high. The President is always glad to have new fraternities founded. That's a good sign.

(7) Any college might have all these advantages, except that of location, and many have something similar to that. But there is one advantage which Dartmouth has which few colleges are fortunate enough'to possess — and that is a guiding, growing, clear-thinking mentality such as is embodied in President Ernest Martin Hopkins. Had I no knowledge of Dartmouth save that conveyed by a twenty-five minute address delivered by President Hopkins a few weeks ago at Symphony Hall in Boston before 1,000 Dartmouth alumni, I would want a son of mine to make that man's college his own. He fits in with the idea of the man who once said that the best college he knew of would be "a young man at one end of a log and Mark Hopkins at the other." President Hopkins is not a pedant. He is a live, growing man. I believe that the imprint of his plastic skill is today visible upon the young men on the campus. He is breeding a new type of college man at Hanover — a better type. And the type he is aiming at will have a more mature and agile mind when graduation day comes around. He wants a man that not only knows the things that have long been taught, but who knows how to tackle today's news, notions, and the job-at-hand thinking clearly, profiting by his educational privileges, and serving himself and others more efficiently.

Yours sincerely, DARTMOUTH 1912.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleReaders of this MAGAZINE will have discovered no doubt

May 1923 -

Article

ArticleRAMBLING THOUGHTS OF A CLASS SECRETARY

May 1923 -

Article

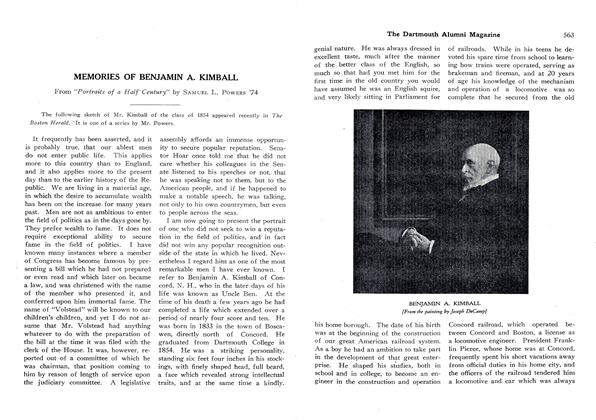

ArticleMEMORIES OF BENJAMIN A. KIMBALL

May 1923 By SAMUEL L. POWERS '74 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

May 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1919

May 1923 By John H. Chipman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

May 1923 By Whitney H. Eastman

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor Negro Impostor

March 1931 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

February 1944 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

January 1952 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

November 1980 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June • 1985