by Raymond Pearl '99, Ph.D. J. B. Lippincott Co.

Raymond Pearl' has given to his book a title which catches the eye of the biologist immediately but unfortunately might not do the same for the layman. The Biology of Death is not, however, for the biologist alone, for it contains a setting of facts and interpretations which it would be difficult to find in any one book and stimulation for thought not only for the biologists but for the general public, including, one might add, even those of Bryan-like tendencies.

Pearl at once asks two questions as an outline for his treatment of the problem of natural death:

"1. Why do living things die? What is the meaning of death in the general philosophy of biology ?

2. Why do living things die when they do? What factors determine the duration of life in general and in particular, and what is the relative influence of each of these factors in producing the observed result?"

And he might have added: What has this to do with our modern social organization? For this last question, while not asked, is one which the book answers and which gives disseminating value to it.

In answering his first question, the author takes the point of view that death is not an inherent potentiality in living matter of itself. He considers the Protozoa immortal as well as tissue-cultures grown apart from the organism from which they were derived. Natural death is the result of organization because of the failure of the component parts equally to cooperate—the organism never being perfectly balanced functionally, though the different types of tissues and cells within the organism are dependent upon each other. This failure Pearl thinks due to the haphazard methods of Evolution whereby that which survives does so when it is just good enough "to get by." (p. 148.)

A mechanistic interpretation of death and of Evolution is consistently held throughout the book, in harmony with prevailing biological opinion. Data gathered from varied sources leads the author to the conclusion that longevity is the expression of a hereditably determined energy endowmetit and not something fundamentally due to environment. Environment is secondary, determining the rate at which the set amount of energy bestowed by heredity is used up. While the improvement of environmental conditions is worth while, the results obtained are small compared to what might be accomplished by eugenic methods. "Men behave in respect of their duration of life not unlike a lot of eight-day clocks cared for by an unsystematic person, who does not wind them all to an equal degree and is not careful about guarding them from accident." " .. if all the deaths which reason will justify one in supposing preventable on a basis of what is now known, were prevented in fact, the resulting increase in the expectation of lifefalls seven years short of what might reasonably be expected to follow the selection of only one generation of ancestry (the parental) for longevity."

Let it be said that Pearl's emphasis upon the importance of heredity over environment is based on a mass of data,' including that from experimental sources, beyond the compass of a review.

No better argument could be advanced by the advocates of birth-control than the last chapter, on "Natural Death, Public Health, and the Population Problem." The author emphatically states the validity of Malthus' original contention and almost despairingly wonders whether human intelligence will ever safeguard the future before calamity befalls. At a time when present restrictions on immigration are being attacked, it is interesting to note that Pearl predicts that the population of the United States will have become "saturated" (no reference to the Volstead Act!) by 2100 A. D.

The effect upon the present writer upon reading "The Biology of Death" is not to question the reliability or suggest the limitation of data for the generalization involved, as one reviewer has done. (Vernon Kellogg in N. Y. Evening Post.) Pearl's compact little book is all out of proportion to the exhaustive amount or reading necessary for its compilation and individual investigation contributed, for it is a condensation involving many essences. On the other hand, certain questions do arise.

If longevity is due to a hereditary quantum of energy, or in other words if death is the resuit of the dissipation of energy derived through heredity, why the immortality of the Protozoa or the in vitro tissue-cultures? I would not question Pearl's contention that longevity is an inherited quality, but his two arguments, death due to the exhaustion of inherited energy, and death being the price paid for organization, seem to be exclusive rather than inclusive of each other. Nor would Kofoid's more recent interpretation of the Protozoa being mortal, in part, relieve the difficulty.

The idea that Evolution is a haphazard process is a difficult one to entertain, for the orderly development expressed by phylogeny does not point to lines derived from helterskelter points, nor the gradual improvement of various organs, to a makeshift, workmanship. Heredity involves stability as well as variability, conserving gains made as well as initiating new advances. Or is this view merely the environmental effect on a morphologist during the depletion of his inherited energy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES, APRIL 27 AND 28

June 1923 By E. M. STEVENS '01, J. W. WORTHEN '09, C. E. SNOW '121 more ... -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

June 1923 -

Article

ArticleAs the Commencement season draws near,

June 1923 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

June 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

June 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

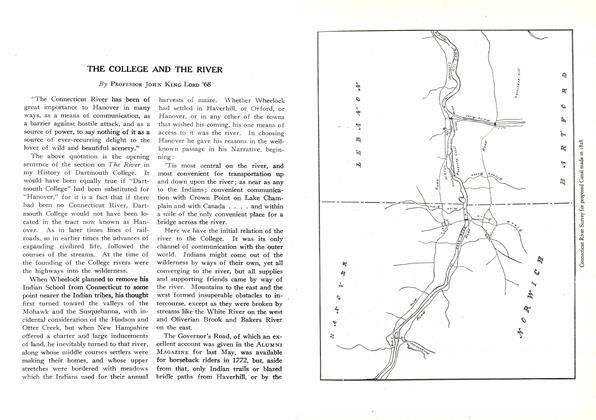

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND THE RIVER

June 1923 By JOHN KING LORD '68

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

January 1924 -

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

June 1935 -

Books

BooksThe Diplomacy of the War of 1812

By J.F.C. -

Books

BooksA Cry Out of the Dark

February 1921 By Kenneth Allan Robinson -

Books

BooksMARKETING MANAGEMENT.

January 1962 By Louis P. BUCKLIN '50 -

Books

BooksA State and Its People

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Richard W. Mallary '49