"The Connecticut River has been of great importance to Hanover in many ways, as a means of communication, as a barrier against hostile attack, and as a source of power, to say nothing of it as a source of ever-recurring delight to the lover of wild and beautiful scenery."

The above quotation is the opening sentence of the section on The River in my History of Dartmouth College. It would have been equally true if "Dartmouth College" had been substituted for "Hanover," for it is a fact that if there had been no Connecticut River, Dartmouth College would not have been located in the tract now known as Hanover. As in later times lines of railroads, so in earlier times the advances of expanding civilized life, followed the courses of the streams. At the time of the founding of the College rivers were the highways into the wilderness.

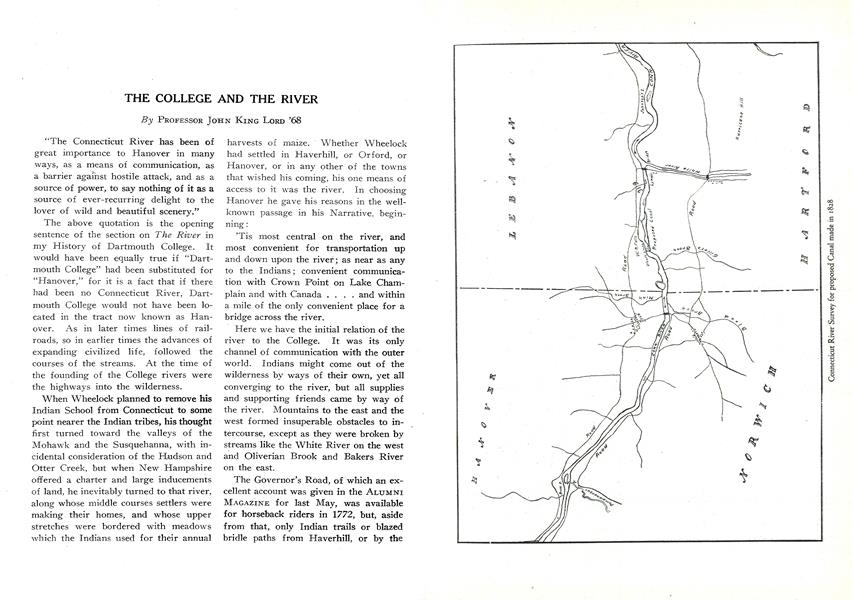

When Wheelock planned to remove his Indian School from Connecticut to some point nearer the Indian tribes, his thought first turned toward the valleys of the Mohawk and the Susquehanna, with incidental consideration of the Hudson and Otter Creek, but when New Hampshire offered a charter and large inducements of land, he inevitably turned to that river, along whose middle courses settlers were making their homes, and whose upper stretches were bordered with meadows which the Indians used for their annual harvests of maize. Whether Wheelock had settled in Haverhill, or Orford, or Hanover, or in any other of the towns that wished his coming, his one means of access to it was the river. In choosing Hanover he gave his reasons in the wellknown passage in his Narrative, beginning:

'Tis most central on the river, and most convenient for transportation up and down upon the river; as near as any to the Indians; convenient communication with Crown Point on Lake Champlain and with Canada .... and within a mile of the only convenient place for a bridge across the river.

Here we have the initial relation of the river to the College. It was its only channel of communication with the outer world. Indians might come out of the wilderness by ways of their own, yet all converging to the river, but all supplies and supporting friends came byway of the river. Mountains to the east and the west formed insuperable obstacles to intercourse, except as they were broken by streams like the White River on the west and Oliverian Brook and Bakers River on the east.

The Governor's Road, of which an excellent account was given in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE for last May, was available for horseback riders in 1772, but, aside from that, only Indian trails or blazed bridle paths from Haverhill, or by the Mascoma valley, or by Walpole and Keene, gave communication with the east. A road up and down the Connecticut, opened in 1762 to 1764 and "inconceivably rough", allowed the passage of oxcarts and even of Wheelock's coach, in which Madame Wheelock came to Hanover in 1770, but transportation by such a route was almost impossible and, despite the several carries necessitated by different rapids, boats on the river were the established means of conveyance in the summer, while in winter the ice furnished a good road for sleds.

To receive the freight thus brought there was a landing on the west bank, but after the location of the College, there was a landing place at a little beach on the east side just under the end of the present bridge. At that time the bank below did not fall sharply to the water, but there was a level strip several rods wide between the hill and the river, on which there was a road leading to the meadow at the mouth of Mink Brook. At some time Blood Brook on the Vermont side did not reach the river by its present channel, but by one that opened just below the rock on which rests the western abutment of the bridge.

As roads along the river were improved and others were opened to the east and the west, the traffic on the river declined, but between 1820 and 1830 an ambitious scheme of river transportation was set on foot, by which steamboats, making use of extensive canals and slack water navigation, were to ascend the river in regular trips as far as Wells River, arid one boat actually made the trial, but the development of the railroads, together with its own inherent difficulties, put an end to the scheme.

While the river was an aid to travel up and down, it was also an obstacle to crossing, and ferries were early established. Of course, there was one (of which the charter was given to the College by Governor Wentworth), starting at the landing place, and there was a second, also included in the college right, of which the place and character are indicated by the name "Rope Ferry Road", still applied to the way leading to it.

But ferries, though helpful, were inconvenient and a movement, led by Rufus Graves, a graduate of the College in 1791 and then an enterprising merchant of Hanover, resulted in the erection of a bridge in the same place as the present one, in 1796. "It consisted essentially of a single span of 236 feet chord, arched to such a degree that the roadway at the center of the bridge was about twenty feet higher than at the ends". But I have written of this and later bridges in my History of the College, and it will be enough to say here that the bridge now standing was opened in 1859, and being the first free bridge over the river was appropriately called the "Ledyard Free Bridge".

The barrier which the river opposed to travel before the days of bridges is believed once to have saved the village and the College from destruction. In October, 1780, a party of Indians, diverted from an attack on Newbury, was prevented from an attack on Hanover only by their inability, or unwillingness, to cross the Connecticut, which at that time was so swollen that even if they had beer? able to cross to the Hanover side they did not dare risk a retreat across it in case they were attacked. Turning away they wreaked their fury upon the towns in the valley of the White River.

Still another service which the river rendered to the College in the early days was to furnish a considerable supply of food. When I was a boy I had a little book—whether it was a geography or a history I cannot tell—which had in it a picture of an Indian standing on a rock in the rapids below Hanover, where Wilder now is, and having in his hand a spear which he was just on the point of hurling at a fish, dimly outlined in the water, I do not suppose that Wheelock ever saw that picture, but he probably saw the Indian and learned that in the season salmon ran up the river; at any rate he mentions this fact in his enumeration of the advantages of the location of the College.

The College has never been interested in the river as a source of power, but it was Mills Olcott, the treasurer of the College and a trustee for many years, who built the first substantial dam and locks at the falls, which to this day bear his name. The locks were serviceable in giving passage past the falls to boats, and to logs that were rafted down the river in immense numbers. There were mills, too, of various kinds, which he constructed, and which after fifty years of intermittent use were carried away by flood, or. dismantled after the dam was broken by freshlets.

The construction in 1883 of the present dam for the mills at Wilder turned the river into an extended lake and entirely obliterated the rapids at the Narrows and at Chase's Island. With the passing of old conditions the College has turned from the material use of the river to the enjoyment of it. It has always been, though more in former days when Commencement came late in July or in August, a favorite resort of the students for bathing, but owing to its rapid current and its shifting bottom it has been the cause of several tragic deaths.

The river has always invited to boating, and many persons have had boats, and in late years canoes, upon it. At times there have been strong boating clubs among the students, sometimes, as in the early sixties, in quite active rivalry, and at one time, in the seventies, there was a vigorous organization for intercollegiate competition. But both stream and climate were hostile. The strong current before the building of the dam, the many freshens, and the ice in winter ranged all the way from hindrances to prohibitions. Twice -nature has intervened to destroy both boats and boathouses, once in 1857, when a sudden freshet in August carried away the landing raft and seven boats with it, and again in 1877, when the weight of snow caused the roof of the boathouse to collapse, and the house and all the boats stored within it were destroyed. Since the latter experience organized boating has not revived, but a canoe club exists at present and in the fine afternoons of summer and autumn the river is often enlivened with the canoes of those who find that in the management of such craft the poetry of motion is in harmony with the enjoyment of nature.

Herein lies the charm of the river today. Its placid surface tinged by the reflection of the overarching blue, or roughened to somber shade by wandering breezes, its winding course, its banks on which sunny meadows, wooded slopes and jagged rocks succeed each other in picturesque association, its occasional Islands, the brooks or the lesser rivers that, rising in the distant hills, steal out of the transverse valleys to lose themselves in the larger flood, the play of light and shadow on the water and on the land, an"d the ever changing views, in which mountains and hills in the verdant mantle of summer or the blazing robes of autumn play hide and seek with one another as they appear and disappear over fields of waving grass or grain, all these combine to allure one who is not insensible to the beauty which nature here so lavishly bestows. Here each one can find stimulus to his thought and recreation for his body, and in winter, as in summer, the same is true, for the austere beauty of the snow, as it glistens along the course of the river, or near and far on the surrounding country, invites to observation and acquaintance.

Once, it may be said, the river was an essential factor in the support of the College in the opportunity which it offered for the transport of physical supplies, now, perhaps, it is not less effective in ministering through the richness of its scenery to the esthetic and spiritual cravings, whose satisfaction is necessary to insure the highest development of men.

Ledyard Bridge fifty years ago

Olcott Falls in i 862

Olcott Falls 1882 From Professor Lord's "History of Dartmouth College"

The old locks at Wilder

A logging crew in the seventies

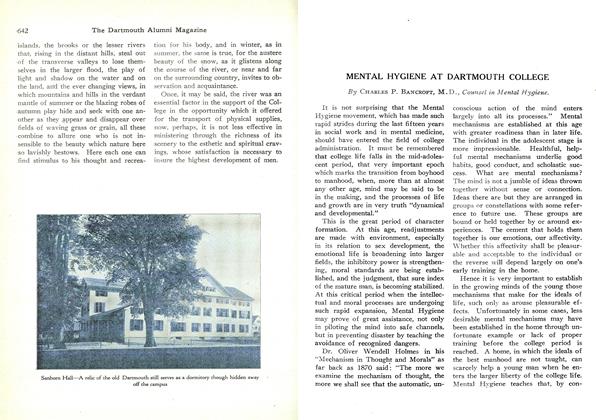

Sanborn Hall—A relic of the old Dartmouth still serves as a dormitory though hidden away off the campus

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES, APRIL 27 AND 28

June 1923 By E. M. STEVENS '01, J. W. WORTHEN '09, C. E. SNOW '121 more ... -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

June 1923 -

Article

ArticleAs the Commencement season draws near,

June 1923 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

June 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

June 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleMENTAL HYGIENE AT DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

June 1923 By CHARLES P. BANCROFT, M.D.,

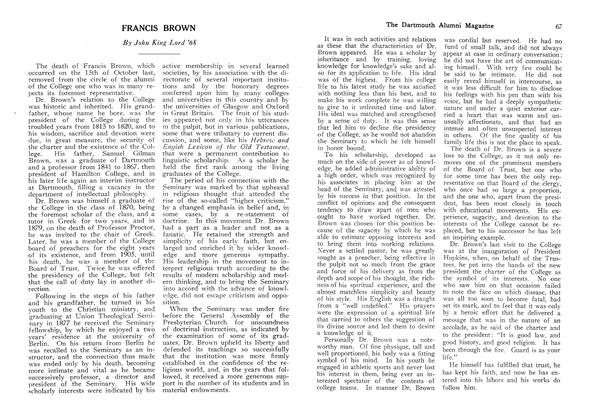

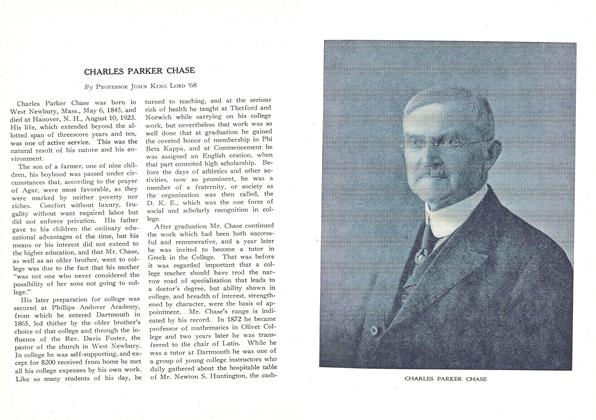

JOHN KING LORD '68

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe College

December 1974 -

Article

ArticleThe Alumni Council's 148th

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Article

ArticleRequired Reading

MARCH 1999 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

April 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleKKR's Counselor, Class of '61

APRIL 1989 By Bob Conn '61 -

Article

ArticleHow Dick Babcock '40 Played the zoning game

MARCH 1988 By Dick Bowman '40