with its various problems affecting the future of men who have for four years been leading the well-ordered life of undergraduate routine, it may be in order to bring forward for a momentary consideration the idea of foreign travel as a not altogether inappropriate or unproductive adjunct to the college curriculum. Of course a great many more college men, either during their course or at graduation, are wont to seek out the attractions of Europe than did so a generation ago. In the early '90's the Dartmouth students who went overseas were few indeed and no doubt were rather accustomed to "give themselves airs" not invariably appreciated by their fellows. It is certainly very different now. The late Professor Charles F. Richardson commented on the fact that in the "new Dartmouth"— contrasting with the old—he found the freshman very frequently arriving at Hanover with his belongings in a steamer trunk, the labels on which bore colorful witness to the owner's recent familiarity with eligible continental hotels. Seldom enough was this to be said of any junior in college 30 years ago. Almost never was it true of any freshman.

It needs hardly to be reiterated that foreign travel is a costly business, for like every other thing it is more so than ever since the war. The point to be stressed is that the fact of costliness does not imply that such travel is by any means, or necessarily, an extravagant luxury. Properly undertaken and carried out, even a brief experience with Europe and the British Isles is certain to be well worth the money put into it by any moderately intelligent and observant college student —preferably with the advantage of the greater maturity of the upper classes.

The idea is in no sense a novel one save perhaps on thesside about to be elaborated. One is familiar enough with the British theory, so often mentioned in famous novels, that the education of no young Briton of any pretensions to culture was complete until he had made the "grand tour"—usually in the care of some tutor whose functions mingled those of the professor and chaperon. The educational value of such a journey, covering all the more celebrated sites between Calais and Naples, was keenly felt. One took this journey as a matter of course, just as one sought out Oxford or Cambridge, and then drifted into the army, the navy, or the church. It was part of the gradus ad Parnassum.

Naturally this is a different matter with people so remote from Europe as Americans. Where the young Oxonian has only to cross the Channel to attain continental Europe, the young American must cross an ocean, and very likely half our own continent as well, as the mere vestibule to his "grand tour." Nevertheless the idea is spreading that, with all the expense and effort, the voyage is worth the making as a purely intellectual expedient, designed to make of the youthful voyager a broader-minded and more intelligent man. "I am a man," quoth the eloquent Roman, "and hold that nothing pertaining to humanity is alien to me." Moreover, fight the theory as we may, the American nation is no longer capable of its ancient aloofness, as if it dwelt in a separate star. It is well to know the world—most of all the world with which our interests are most intimately bound up and our future concerned.

Our collegiate education has for some years tended away from the cultural toward the practical. In the estimation of the present editors it has exaggerated this tendency somewhat beyond the desirable point. For such as have omitted the socalled "humanities" from their previous study it is very possible the European journey will prove a needed antidote. It will most certainly awaken new interests in the older civilization whence our own derives. It is likely to make vivid to the satisfied mind that, despite the enthusiasm of educators for the modern languages as against the ancient, one has still much to learn of that incomparably idiomatic linguist, the average European concierge. The pity is apt to be that one appreciates only when it is too late the impressive reality that we are a part of all that we have met. Even so, it is better late than never.

That foreign travel has its practical as well as its purely cultural side deserves a further word. One of the greatest of our American editors—probably the most distinguished who is still living—once told the students of a well-known school of journalism that if he had his choice he would charter a ship, fill it with the most intelligent youths he could find, and set out on a two-years' cruise around the world. "At the end of that time", said he, "those young men would be better fitted for practical newspaper work than if they had spent four years in purely professional study." This is not true to the same degree, perhaps, of other callings ; but it is so far true that no young man who has the opportunity should ignore the chance to make acquaintance of the outside world while he is young, impressionable, and free from the hidebound prejudice of rooted custom.

This MAGAZINE, as we are well aware, addresses itself to alumni and is read little, if at all, by undergraduate students. However, what has been said is not by any means misdirected if it inspires any father, sincerely anxious for the intellectual equipment of his sons, to recognize the great importance of foreign travel as an adjunct to the college course. One knows also the inevitable rejoinder that one should "see America first." That familiar dictum seems to us open to honest dispute without the implication of any lack of patriotism. A thorough knowledge of one's own country for practical purposes is a matter of course and no one denies its desirability. That one must necessarily make pilgrimage to all its parts in order to attain such knowledge is what one doubts. Meantime to know the world with which we have increasingly to deal remains a duty too little recognized. It is this which we stress, with intent to persuade fathers with undergraduate sons. Send the boy abroad, for two months if for no more, in company with some of his fellows. There's more education in it than in half the schools.

The vexed problem of finding an ideal method for nominating alumni trustees still defies satisfactory solution, although this is not for want of active and interested debate. It has long seemed to us that the objections raised concerned methods rather than results—i.e., that the alumni, while reasonably satisfied with the high quality of trustees elected from among their number, felt vaguely that the nominating machinery which produced this admirable result was not sufficiently close to the electing body and should be democratized. The question then arises whether it is sufficiently important to engage so much attention - whether it is not on the whole wiser to let well enough alone, assuming the real question to be purely of means rather than ends and further assuming that the quality of alumni trustees is already entirely suitable to the tasks they must perform. On this the MAGAZINE cannot dogmatize, but it feels that it may at least raise the question in a general way. If the nominations as currently made give us a highly competent board, if a change to a sort of direct primary would not sensibly increase the ability of the trustees, and if such change were to suggest a diminution rather than an enhancement of the ability, is it actually worth while to amend the system?

In its present estate the problem rests thus : A change suggested by the Executive Committee of the Secretaries Association (whereby the Alumni Council, after canvassing the alumni body, was to make final nomination without reference to the alumni as a whole) has been withdrawn from consideration and the whole matter recommitted. Meantime the usual custom of submitting but a single nomination has been followed by the Alumni Council, and thus far the returns reveal a much greater interest than has been common.

It may be worth a thought if we analyze the underlying premises on which the agitation for a change is based. If it rests on dissatisfaction with the trustees actually elected by the current method, then surely a change is needed. If it rests only on the ffeeling that an admirable result is being reached in a somewhat informal way, then the necessity for a change is more open to doubt. Which is the fact? Moreover, if the change when made would not be likely to increase the ability of the board, but might conceivably militate against its maintenance at the present admittedly high standard, it would seem to be a question whether the price to be paid for the mere sake of a formal alteration was excessive. No attempt is made here to decide among these alternatives. The idea is only to suggest a thoughtful consideration of the possibilities and most of all a candid diagnosis of the case—not so much to determine the nature of the disease as to determine whether there is in fact any malady at all to be cured.

One notes a fairly strong feeling in some quarters that the system now used is "undemocratic" in that it sends out to the alumni a single name and thus reduces the function of the alumni ballot to that of ratification only. True; but the important question is still the pragmatic one. Does it not on the whole work pretty well? Would any change produce a better result? Is there a danger that a change would produce a less agreeable one? In fine, is the great desideratum to procure the best possible board of alumni trustees, or is it to seek first a democratic-looking electoral machine and take a chance on its working well ? It seems proper to caution debaters once again to avoid confusing methods with ultimate results, especially if there is danger of detriment to the latter. "Whate'er is best administered is best." The charge that the present system was slowly ruining alumni interest by making the election perfunctory seems to be weakened by the great increase in this season's number of ballots—but that may be sporadic only. The charge has seemed plausible enough. Our query is whether this charge, if sustained, is especially important after all, if it be admitted that the board of trustees is already as able a body as we are likely to obtain under any system ?

Changes of no very surprising kind appear to be foreshadowed by a recently promulgated announcement by Harvard University that in the future students would be admitted on certificate from approved schools provided they stood in the highest seventh of their class at graduation. This, while falling far short of the system which Dartmouth has employed for the past four or five years and certainly far short of the present selective system, seems to the MAGAZINE to be sufficiently similar to indicate a trend away from the ancient reliance on examinations as the sole test of entrance qualifications. Even so, however, it goes but a little way on the road. It is fairly safe to assume that any student who at graduation can stand in the first seventh of his class would certainly pass the Harvard examinations; and the exemption of such from the necessity of taking such examinations amounts chiefly to eliminating needless work which one may quite safely take for granted. What one may not unreasonably look for is a broader extension of the principle, so that less and less insistence shall be laid upon the rank attained by an applicant in examination, and more and more stress laid upon his work during the final three years in his preparatory school as more trustworthy index of his capacities and possibilities. This innovation, already more fully welcomed at Hanover than elsewhere but by no means unrecognized in other colleges, will make headway solely because of its obvious logic. The one obvious chance for weakness lies in laxity in designating an "approved school". In that respect one must indeed be careful. But given the proper grade, surely the year-in-year-out performance of a young student should give the most reliable index of his attainments. Nevertheless the original notion persists that the way to discover the student's powers is to ask a set of questions rather than take note of his work in ordinary action. Erosions such as that indicated by the Harvard statement are likely to increase in future years.

Webster Hall

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES, APRIL 27 AND 28

June 1923 By E. M. STEVENS '01, J. W. WORTHEN '09, C. E. SNOW '121 more ... -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

June 1923 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

June 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

June 1923 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

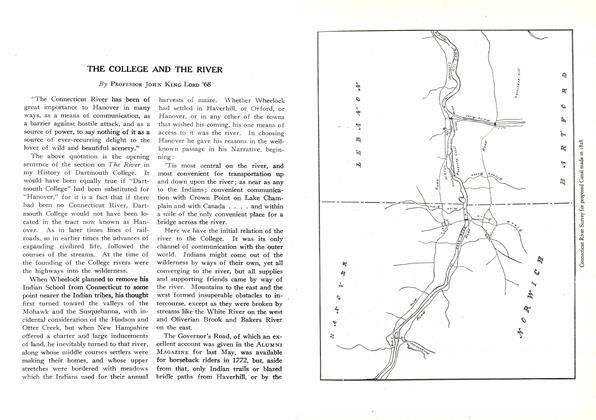

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND THE RIVER

June 1923 By JOHN KING LORD '68 -

Article

ArticleMENTAL HYGIENE AT DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

June 1923 By CHARLES P. BANCROFT, M.D.,