Reprints are enriched by the issuance of a reproduction of an article by Professor Herbert Darling Foster on "Webster's Seventh of March Speech and the Secession Movement, 1850" which originally appeared in the American Historical Review (Vol. XXVII, No. 2; January, 1922). This article is of peculiar interest because it not only deals with a famous and historic utterance, which had a vital bearing on the history of the country, but also concerns a much questioned incident in the life of the most illustrious alumnus of Dartmouth College.

Professor Foster, in a thoughtful and well documented paper, seeks to correct a mistaken impression of the famous speech whereby Webster sorely offended many of his abolitionist friends in the North. The apparent conclusion is that there certainly did exist a real danger of Southern secession in 1850 and that Webster, in taking the attitude he did, sought only to preserve the Union at the risk of his personal and political reputation. The belittling assumption that in this address Webster was actuated by the hope of attaining to the presidency is analyzed and refuted. In this the author is advantaged by the lapse of time sufficient to permit a real perspective, unembarrassed by the acerbities which animated contemporary critics of Webster; and he is also benefitted by the opportunity to examine and to cite numerous private letters which indicate how false were many of the assumptions, both as to the existing dangers and as to Webster's personal feelings, that prevailed at the time and for many years after. A distinct service to history is thus rendered which deserves more than this passing notice.

It is at all events made clear that Webster could have had no self-aggrandizing motive. He did not make himself friends in the South. He alienated a great many supporters in the North. He knew perfectly well that he was doing both things, and the allegation that he made this utterance in the hope of increasing his prospects of becoming president of the United States is therefore manifestly absurd. But the great achievement was that he drove a wedge dividing the South temporarily against itself, postponing the actuality of secession to a later day and gaining what he doubtless hoped would prove sufficient cooling-time which might avert the struggle altogether. In the latter hope he was certainly deluded. But it is altogether probable that the delay which his compromising tactics secured was for the advantage of the Union cause and was therefore statesmanlike, rather than the characteristic of a mere politician. It is perhaps natural that it should have required nearly three-quarters of a century to give the country a just appreciation of this much criticized act, and it suffices to show how prolonged must be the time before a fully candid appraisal can be made of an historical event or utterance. It is also interesting to discover that by no means all of Webster's Northern friends were alienated by this effort to hold the South in line, although to extremists it naturally seemed a covenant with death and an agreement with hell. Interesting, too, to find such a clean-cut dissection of the erroneous views to which so eminent an historian as Mr. Lodge gave currency some 40 years ago; but of course that proves chiefly the folly of writing dogmatic history too soon after an event. We commend Professor Foster's article to all thoughtful alumni as an extremely valuable footnote to history.

In line with what has been said in these columns in past months concerning the tendency of education to multiply processes and augment costs comes the significant address recently delivered in Philadelphia by Nicholas Murray Butler before a convention of educators, in which the most important utterance was that education suffers from a very prevalent delusion; to wit, that "the more elaborate and the more costly the machinery of school organization, the better will be the product." President Butler went on to say that the reverse was the fact and that the menace of over-standardized, government-made uniformity in such a matter could hardly be overestimated. Bureaucratic regulation, he felt, was not an ally of education but a deadly foe. He expressed himself as very strongly against the idea that public school education should be federalized under a department with. a secretary sitting in the cabinet—a proposition which he held was flattering to the, professional vanity of pedagogs, but nothing else.

Beyond doubt the country will eventually have to face this problem of nationally directed education, which has abundant precedents in other (but much smaller) countries. The difficulty is to draw accurate analogies between education in the broad territorial extent of the United States and education in compact and constricted European countries, no larger in acres than some of our single states. What works well enough in a country the size of France or Germany may not work so well in a land so infinitely wider spread, and above all composed of so much less homogeneous a population. But the movement is well under way and it is doubtless to some extent based on the familiar idea that the more progressive states ought to bear the cost of bringing the more backward states up to a better standard. It is argued that this is for the. country's general interest and that it would sufficiently benefit the progressive states to warrant their making up other people's discrepancies in mere money. Hence the measures in Congress formerly associated with the name of Mr. Towner, designed to take the business of public education out of the hands of thousands of scattered communities, and out of the power of individual states, to vest it in the central government at Washington, with a federal bureau and a cabinet officer in charge. It is the natural outcome of several regnant passions, among which is the passion for standardized humanity, to which the amazing successes of Mr. Ford in the line of insensate machinery have contributed much. But there remains the shrewd suspicion that the real incentive is the desire to get someone else to pay the bills which certain of our more backward commonwealths refuse to incur and pay, when left to their own devices.

It is not the function of this MAGAZINE to dogmatize in such matters. All it may appropriately aspire to do is lay a finger on certain outstanding objections, as well as on certain salient recommendations. It might well first advise a careful reading of Dr. Butler's Philadelphia address as a very pertinent commentary, not only on this plan for federalized education, but also on the process which Professor Pattee not long ago summarized as "unseating Mark Hopkins" and apotheosizing the "log" on which that ideal teacher sat. The contention that the process of elaborating and standardizing, as far as it has gone, shows deplorably little improvement in the educational product deserves a thoughtful consideration, to discover whether or not it is true. The suggestion that the farther we remove education from the community's intimate control, the less efficient it is likely to be, merits no less careful attention and to us sounds, at first hearing, like good sense. Is it desirable that an American Secretary of Education be able to say to the president, as a French educator once was able to say to King Louis, "Sire, at three o'clock this afternoon every schoolchild in the country will be translating a page of Julius Caesar?" Can immature children be treated as wax to be poured into a mould? Is what we really want a sort of Ford-humanity?

In fine, while there is doubtless much to be said for the federalization of public schools, there is much to be said against it—and Dr. Butler is a most admirably qualified critic for the purpose of saying it.

There are "outs" about everything, no matter how you arrange it. There are decided outs about the school system as conducted by the community oversight method, familiar to us in New England and elsewhere. State control has proved more or less shadowy and the real control is manifested by local committees chosen by popular vote, whose expertness is often meagre and more often still does not exist at all. It is easy to argue from the steadily worsening conditions of city politics and from the tendency to make the city school committees openly matters of race and religion, that a federalized system, even if defective in many ways, could hardly be worse than what the cities are coming to have now. This, while it has a certain plausibility, is probably not entirely true. At all events it is wise to discover what would be the probable defects of a public school system controlled from Washington before assuming that they would be less intolerable than the defects incident to ward politics as commonly conducted in even our subordinate cities. Federalized education will have to fight its way against a determined, and on the whole plausible, opposition; and curiously enough the religious issue, on which so many cities fight out their school board contests every year, seems entirely to break down when it comes to considering federalized education, the opposition to the latter coming from Protestant as well as Roman Catholic sources in about equal intensity though for different reasons. President Butler's energetic opposition well typifies the arguments most generally urged.

If we may judge by the groanings of spirit heard of late from rooms devoted to faculty assemblage, there is at least some measure of truth in the statement that the product now being turned out by the country's various schools, public and private, is not of an excellence proportionate to the elaborate and costly mechanism employed in its production. We are spending more money than was ever before spent on the process of training the youthful mind to function—but are we getting minds that really do function any better than those less elaborately trained ? Do they even function so well?

Not long ago in an issue of the Harvard Graduates' Magazine there was printed a thoughtful article by President (emeritus) Thwing of Western Reserve University, devoted to an examination of th'e question, "What Studies Make Mind ?" The basis of the discussion was an analysis of the list of men who graduated with honors from, the Harvard Law School during the 42 years from 1880 to 1922. These honor men, who numbered altogether 709, came to the law school from 104 different colleges. Dr. Thwing has tabulated the results of his investigation of what one may call their intellectual provenience, in the hope of discovering something definite as to what studies, previously pursued in college, most commonly presage a career of distinction in graduate studies of a peculiarly rigorous kind.

It is difficult to draw from the published data anything very dogmatic. It is developed, however, that although the classes at this famous Law School have grown tremendously in numbers with the years, the number of honor men has not grown proportionately. Where, in early days when classes numbered perhaps a score or two dozen, there were usually about a third of the whole enrolled as specially distinguished by honors awarded, we now find that when classes number close to 200 the number of honor men is around 34. The standards and method of examination remain about the same throughout. Is the failure of honor men to keep proportionate growth with the size of the classes due to changes in the preparatory curriculum ?

It is greatly to be feared that conclusions drawn from such data are liable to misconception. The most general statement, however, that it seems safe to make is that the men who show scholastic excellence in college are generally the ones who show a similar high grade of excellence in the professional schools ; and that those who have "majored" in certain groups of studies while in college—concentrating on a few related studies—usually reveal a superior mental training. But whether the best results are attained by "majoring" in the classics, or in mathematics, or in political science and history, or in modern languages, is a question which it would be rash to dismiss in a general formula.

What's one man's meat is another man's poison. It is impossible, we believe, to reason from the fact that the classics prove most beneficial to some men to a general conclusion that they must be the same for all. It is, however, notable that certain authorities quoted by Dr. Thwing pronounce unreservedly for Greek and Latin as approved subjects for training the legal mind. "Feed me with food convenient for me" is a< prayer which applies with especial force to the making of the mind, and the food convenient for one individual may not be that which best suits another. The great aim of every college is to teach its young men to make the best use of the mental tools with which they are endowed. "To think broadly without shallowness, deeply without narrowness, and highly without visionariness" is an ideal well phrased by Dr. Thwing. The best mental pabulum to that end remains an elusive thing, as to which it is dangerous to dogmatize. There are numerous appliances in the intellectual gymnasium, all intended for a common purpose; and some doubtless use one set with more advantage than another, without proving that their experience is a criterion by which the case of all students may be judged.

Nor is the law school the only sort to be taken into account. The conclusions reached as to what studies best develop the mind for legal study may conceivably differ from those reached as to what studies would best prepare the way for a course in engineering, or business, or medicine. The thing which is most elusive of all is the determination of what studies best prepare the mind for anything and everything—distinct from professional specialization. Can a preference be awarded to languages, ancient or modern, over the sciences? Or to sciences over languages and history ? This we doubt. Minds differ so, and young men often awaken so late to the opportunities. Besides, we are not really seeking studies which shall "make" mind, but studies which shall exercise and develop mind already made.

What study comes the nearest to being a master-key? It is desirable that the graduate equipped for opening the doors of knowledge be provided with such a thing, if it exists, rather than with a cumbersome bunch of individual keys each adapted to some special lock—more particularly if, as often happens, one does not know while in college exactly what line of life one is to follow. The liberal education properly means that which fits man for any society, any sort of life. It is a question whether American education, as latterly developed, has this fact sufficiently in mind. Pedagogical experts have seemed to be intent on giving to the rising generation varieties of keys fitted to diverse locks, rather than a skeleton key which would serve equally well for a variety of portals. There is always an eye on the professional future, on vocational training, on what is commonly called "success in life", to the exclusion of the enjoyment of life when one shall have succeeded, or to the solving of the common problems of citizenship which arise in every career regardless of its professional activities.

For the colleges to anticipate too zealously the needs of professional students we believe to be a mistake. The college is not a training school but a college, where immature minds are sought to be adjusted and provided with certain common essentials of appreciation, or given a grasp on certain aptitudes, which must be specially developed later. Whether our present department store brand of education turns out better equipped men than did the simpler systems of an elder day remains matter for dispute. One judges by the minds actually turned out, rather than by the imposing, mechanism employed in the process. The rude old enginery did a pretty good job, for all its simplicity. It set young minds to working and they worked well. The number of honor men in Harvard Law School was even greater in proportion in the 'Bos than it was in the early 1900's.

As usual the midwinter season was marked by the convening at a central point of the students from various colleges and universities representing as delegates that portion of the student body which likes to talk of itself as conspicuously and distinctively "Liberal". As usual such a meeting prompts a word. The unfortunate propensity of the modern Liberal of the professional sort is to conceive himself or herself as a personage apart—if not flagrantly despised and rejected of men, at least an object of rather welcome suspicion. And it sometimes might seem to a coldly appraising eye that if only these rapt young persons devoted half the attention to getting an education that they devote to being so outspokenly "Liberal", they would lead all their classes and monopolize the honor lists.

This is not to imply any lack of virtue in Liberalism1, properly conceived, but rather to suggest that almost too much virtue may be read into the process of cultivating Liberalism for its own somewhat ostentatious sake. The passion for being publicly immolated on the altars of free thought, free speech—and sometimes even free love—is apparently implanted in a fairly constant number of human beings of all ages at any stage of the world's development you choose. One often seems less concerned for the pursuit of Truth than for the pursuit of the Unusual and the Unlikely. There is occasionally a faint suggestion of the prayer of the Pharisee, thanking God that one is not as other men are. Likewise a distinct absence of any Danish regret that one was born to set things right. But for the greater assurance of mankind, it is to be remembered that the college youth's sense of the ridiculous is generally quite sufficient to turn the worse forms of offending into a telling burlesque and thus prevent the less tolerable effects of over-done radicalism among those of plastic years.

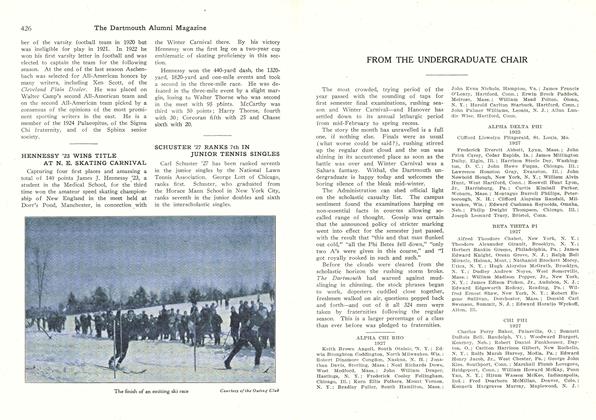

Hanover's greatest thriller,—the ski jump

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN THE SEVENTIES

March 1924 By Samuel L. Powers '74 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1924 -

Article

ArticleWHAT THE STUDENTS THINK ABOUT AND WHY

March 1924 By Harry R. Weellman -

Sports

SportsBASKETBALL

March 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

March 1924 By H. Clifford Bean -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March 1924 By David Lambuth