By William Lyon Phelps. Marshall Jones & Co., Boston.

The Dartmouth alumnus of the earlier the Guerrfsey Center Mioore Foundation have called many distinguished scholars to Hanover. One series of these lectures was delivered in 1923 by William Lyon Phelps, Lampson Professor of English Literature at Yale. Some time after their delivery these six lectures were published in an attractive volume by the Marshall Jones Company of Boston.

This book is not a college text-book nor a series of critical essays, and it makes no attempt to add to the sum of factual knowledge. It is a transcript of the delightful lectures themselves, delightful to the appreciative audiences who originally listened to them, for the gracious urbanity of their tone, the telling facility of their phrasing, the novel ordering and marshalling of their information, and the sympathetic and understanding presentation of a new and personal point of view concerning those eighteenth and nineteenth century writers who made the most noteworthy and valuable contributions to the making of American literaature.

The Dartmouth alumnus of the earlier classes who reads this book will immediately revert to his memory of a very similar, because intensely personal, treatment of the same themes by the late Professor Charles F. Richardson, who, like Professor Phelps, had the ability of so presenting his opinions about literature that his listeners were not content until they had read for themselves the very books of the author whose work was discussed, criticised, and evaluated. Like Professor Richardson's method, too, is Professor Phelps' insistence upon the importance of the personality of the writer in the production of his work, that only great and strong men can produce great and lasting books.

The figures so adequately treated are Frankiin, Edwards, Cooper, Webster, Lincoln, Hawthorne, Emerson, and Mark Twain, each as representing one essential phase of that complex whole which we call the American spirit, and to which each of them contributed from his own rich personality. Whether Professor Phelps is talking of the man of God, the man of the world, the political idealist, the serene philosopher, or the great mirth-maker, he always holds our interest,—not because his facts are new but because he has thought newly and freshly about them, has thought about them with the alert mind of a shrewd, sensible, mature, and cultivated scholar, whose learning is not a mere accumulation of knowledge, but the zestful understanding of the meaning of it all.

'To repeat, listening attentively to what Professor Phelps has to say about American literature—and you can listen to him in no other way—makes the hearer want to read the literature itself. F. P. E.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

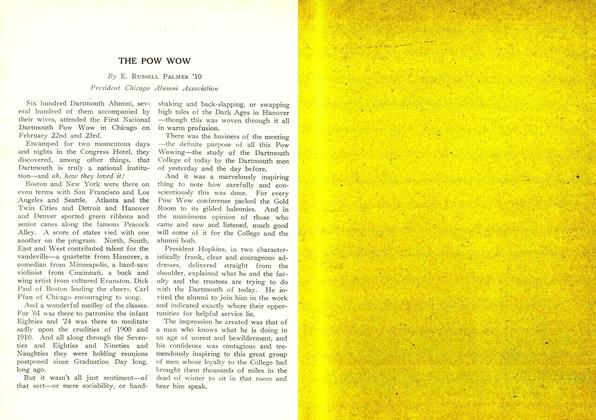

ArticleTHE POW WOW

April 1924 By E. Russell Palmer '10 -

Article

ArticleIS THE COLLEGE EDUCATIONAL PROCESS ADEQUATE FOR OUR MODERN WORLD?

April 1924 By Charles Dubots '91 -

Article

ArticleThe Chicago Pow Wow which

April 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

April 1924 By H. Clifford Bean -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth

Books

-

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

NOVEMBER 1969 -

Books

BooksTHE DARTMOUTH SCENE

January 1950 By Charles A. Proctor '00 -

Books

BooksPEN-DRIFT: AMENITIES OF COLUMN CONDUCTING

APRIL 1932 By F. L. Childs -

Books

BooksFRANCISCO DE ALDANA POESIAS.

July 1958 By FRANCISCO UGARTE -

Books

BooksGRAMATICA ESPANOLA DE REPASO.

July 1958 By JOSEPH B. FOLGER '21 -

Books

BooksPOETS OF TODAY II.

December 1955 By Lou B. NOLL