Just before the coming of Columbus more than 15 million people lived in and roamed across all of North America above the Rio Grande. By the turn of this century their descendants - less than 210,000 - lived (in a manner of speaking) confined to this nation's most undesirable land. What happened to this proud people and to the land they once held is the focus of Joseph Farber's and Michael Dorris' magnificient book.

It is actually two books bound in a single volume. Much of it is devoted to Farber's black-and-white photographs of the present-day Native Americans who live in the contiguous United States and Alaska. This photographic record is a masterful portrait - often harsh and brutal, frequently warm and poignant - of a proud and spirited people trying desperately to cope with the America of our time, and trying still to maintain the dignity and richness of their past history and heritage. Seldom has such a record of pride and frustration, tragedy and triumph, a past and a present been depicted so superbly - without glossing over the seamier side of today's Native American agonies.

The second book in Native Americans is Michael Dorris'. His admirably lucid account of 500 years of Native American history serves as a preface to Farber's book and a chronicle of the deceit, treachery, and cunning practiced by Europeans and white Americans against the Native Americans. The history Dorris tells is an ugly one - a history marked by disease and broken treaties, two bitter "contributions" passed on and forced upon Native Americans with the advent of large-scale exploration and conquest of this continent. The tales of horror began centuries ago; and according to Dorris the Native American's inability to cope with disease brought here from Europe, and the failure of Europeans to understand the Native American's concept of land and the treaties that supposedly governed those lands, signaled the systematic destruction of literally millions of Native Americans.

When a treaty was signed with white men, Native Americans assumed that such treaties would last "as long as the rivers run and the grasses grow." But Manifest Destiny in America meant the damming of rivers and the rape of the land.

Such gross indignities did not end with the dawn of the 20th century. Dorris' introduction and Farber's photographs make that point abundantly clear. Disease is still a terrible specter on reservations that are rural ghettos, alcoholism plagues the steps of old and young alike, suicide is rampant, and the life expectancy of Native Americans is almost 30 years shorter than of the whites of this land. In spite of these awesome burdens, there's a power and a vigor among today's Native Americans that signal a reversal of these bitter trends.

I said that Native Americans is two books. Joseph Farber's book most movingly dramatizes what Edward Steichen said was the mission of photography: "to explain man to man and each man to himself." Michael Dorris' book is a trenchant statement of what Chief Joseph, a Nez Percé, said more than a century ago: "We only ask an even chance to live as other men live. We ask to be recognized as men. We ask that the same law shall work alike on all men."

NATIVE AMERICANS: 500YEARS AFTER. Text by MichaelDorris, chairman, Native AmericanStudies. Crowell, 1975. 333 pages,325 illustrations. $14.95.

Professor of English at the University ofConnecticut, Mr. Medlicott spent spring term of1973 teaching at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Way in the World: A Conversation with John Dickey

January 1976 -

Feature

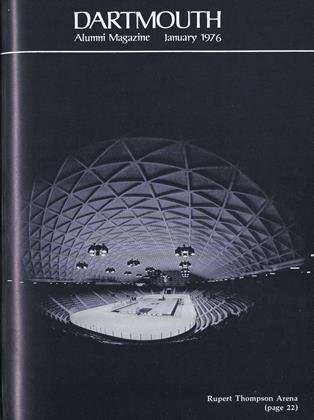

FeatureNervi's Concrete Aesthetic

January 1976 By JOHN JACOBUS -

Feature

FeatureA Season on the Racetrack Special

January 1976 By DAVID DUNBAR -

Feature

FeatureFarewell Dear (BOOZY, BRAWLING) Davis

January 1976 By ROBERT SULLIVAN -

Article

ArticleA Reasonable Balance?

January 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

January 1976 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

ALEXANDER G. MEDLICOTT JR. '50

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

January 1953 -

Books

BooksCanoe Club History

MAY 1967 -

Books

BooksGOVERNMENTAL PROMOTION AND REGULATION OF BUSINESS.

OCTOBER 1969 By ERWIN A. BLACKSTONE -

Books

BooksL'HÉRITAGE FRANCAIS.

January 1954 By GEORGE E. DILLER -

Books

BooksStar-Studded Life

February 1976 By J.B. WATSON JR. -

Books

BooksUNIVERSAL CONSCRIPTION FOR ESSENTIAL SERVICE

November 1951 By Virginia L. Close