Director of Personnel Research, the College and the community lose an outstanding figure and a man whose place it will be most difficult to fill. To Dartmouth he gave the best years of his life, contributing vitally both in the field of instruction and administration. During the war he served the State of New Hampshire, and though flattering offers of other connections resulted from the executive ability he there demonstrated, his abiding interest was in the College and its work.

Professor Husband's greatest service was in the pioneer field of college personnel research. By constant and painstaking effort a mass of correlated, statistical material had been assembled to supplement personal judgment of the characteristics and abilities of the undergraduates. Readers of this magazine will recall numerous illuminating articles from his pen on the problems and results of this research. Many a member of recent classes will remember with gratitude the sympathetic and helpful manner in which his own particular problems were approached and the solution attempted. His work will remain as .a notable contribution of service to the College and the individual.

When it was suggested some months ago that perhaps the problems of the College with respect to curriculum and related incidents might be solved with the more address if it could first be established precisely what the College was tryPerhaps ing to do, it is likely that the first reaction of any alumnus in the Roaring Forties was that of surprise that any one should doubt. Don't we know what the College is trying to do ? Most certainly! And what is it? Well—er—er— possibly thefe is some dubiety after all, especially if one must ask such embarrassing definiteness of those who have thought hitherto in abstractions. At all events some One has put the question plumply; and the effort to frame.a satisfactory answer bids fair to occupy both the graduate and the undergraduate mind for some time to come.

A sort of intellectual inventory is at present going on which involves a thoughtful introspection, as well as much searching of the minds of others at home and abroad, the purpose of which is to make it a little more clear to the College itself what is, or should henceforth be, its mission in life. It is of little worth to sum it all up in the well-known and indisputable formula that "the College is trying to educate young men." That merely begs a number of questions. What is education? For what special, or what general, purposes is education in such a college as Dartmouth designed ? Are we intent on producing a race of erudite scholars, or only a great body of debonair youth to whom "an inkling has been conveyed of the far-spreading realms of human knowledge ? Are we striving to inculcate the means for attaining "success in life," or is the main idea to promote the power to enjoy life, once the individual has attained success ? Is part of the idea to make one indifferent "to success, as spelled in money—or is it to fit one to make and to enjoy the most money possible? Look we for statesmen? Are we training a body of potential prime ministers, as the English universities are sometimes said to aim at doing? If not, should we? Or is the aim to give to the world subalterns for its army of welldisciplined human beings, properly introduced to Dame Knowledge, equipped with a certain ideal—it may be but halfguessed and still be as real as any ideal ever can be—and fitted, in the majority of cases, to make the world of their day a little better because they lived in it ?

Questions such as these an ingenious person intent on filling a given amount of space can improvise to no end and still emerge, like Omar when young, from the same door wherein he went. It is, however, a fact that the College is at present busily taking account of stock in the hope that something that resembles a definite, concrete, approvable idea may be set forth, in a form which wayfarers may comprehend, concerning the present and appropriate purposes of education in an American college like our own. Once that is clearly established it is likely to be the easier to know the best means whereby this end may be served.

To that end not only the ideas of those who have the instruction in charge are being canvassed, but also the ideas of those now immediately in the process of being instructed. And the results appear in the form of an increasing body of documentary evidence, representing the conclusions and theories of such as are presently and personally concerned with education at Hanover.

it has been assumed, and with entire plausibility, that much benefit is'' to be gleaned from the interrogation of actual students—more perhaps than a casual observer would suppose. The first beginnings have revealed a surprising readiness to assist and to assist in genuinely helpful and suggestive ways. There lies before us a rather interesting undergraduate effort to sum up in a paragraph the whole purpose of the College, which runs as follows:

"It is the purpose of the College to provide a selected group of men with a comprehensive background of information about the world and its problems, and to stimulate them to develop their capacity for rational thinking, philosophic understanding, creative imagination and aesthetic sensitiveness, in order to inspire them to use these developed powers in becoming leaders in service to society."

This broad definition it is not the present purpose to analyze in detail, although that has been very ably done brothers. The present purpose is to consider the applicability of this purpose to colleges as they now commonly exist, crowded with young men from every walk of life and every station in society, not a few (it has been feared) in sore need of recognizing something beyond four years of enjoyable existence in a society which it is fashionable to cultivate if one is to be reasonably "correct." The definition given above seems clearly to presuppose the need of superiority in the raw material from which the product is to be made—something approaching that "aristocracy of brainsv once so much discussed. In other words, the colleges cannot do the impossible and make out of inferior material a highly finished and highly polished product. The very first essential would be a freshman class with latent possibilities to bring out a class devoid of obviously insuperable defects, so far as such can be discerned. Various terse but inelegant proverbs have emphasized the general theory that it is impossible to make a silk purse out of a sow's ear—and the world as a whole inclines to regard this as axiomatic. It is apparent, however, that more or less that is at best not silk has at times been employed as the material for such purses, with results not entirely free from disappointing qualities.

It appears from the very first words of the quoted definition that the primal necessity is greater care in choosing the young men on whom to operate, much as one would do if intent on procuring suitable wood for golf-sticks, or other purposes demanding straight grain, implying freedom from manifest defects and sufficient workability to warrant spending time on it. That it is a dismal waste of time to send some young men and some young women to college is sadly true; and the worst thing of all is that such, by being received may prevent other, and more promising, material from having its chance.

It is probably not wise to expect too much, even of a college with revised ideas of its purpose in the world and the best of good intentions to serve that purpose. After all, we are human. To strive for perfection, while it may not bring us to perfection, should certainly operate to prevent falling too far short of the attainable degree. It has been pointed out many times that while the colleges of this country have grown prodigiously in size within the past 20 years, the proportion of "honor men"—that is exceptional scholars—has not kept pace with the growth. That fact alone is testimony to the general failure to select material with address. Other things being equal, a college which had 25 honor men in a class of 75 should show about 250 honor men in a class of 750. It is not the usual experience that this is so. We doubt that it ever is so. A possible conclusion is that the greater numbers include more of those to whom college education is wasted effort. Generalities are often dangerous, however. It is not always safe to estimate the success of any educational institution by its product of men capable of attaining high marks. It is, however, rather significant when proportions break down altogether, as they appear to do in this case; and due weight, we believe, should be assigned to the fact as showing a change in the situation from what was true of the colleges a generation ago. The greater volume of milk doesn't yield the proper proportion of cream. Can it be made to? Or isn't the cream what we are really after ? Presumably this query figures also in the long list of perplexing inquiries with which the current inventory and survey have to do.

In any case one may await with interest the sifting of opinions which this inquiry is certain to involve, the hope being that in the multiplicity of counsel there may be found, not darkening, but enlightenment.

The quoted paragraph mentioned above is taken from an undergraduate thesis on the general topic and may be regarded as an earnest of the spirit in which the student body is disposed to approach the problem in the solution of which its aid is solicited through the expression of its ideas. There is a certain novelty in asking this aid. It is a clear divergence from the ancient theory that the student's business is to eat what intellectual provender is set before him, asking no questions for conscience's sake. The promptitude and voluminousness of the response indicates at least the requisite interest, and there seems but little occasion to question the attendant wisdom, save as it may be true that the greatest glibness in such matters may not betoken either a long or very deep study. It is also salutary for older men to think back to the days when they also were students and to recall some of the theories then regnant. One of those theories some thirty years ago was, as we recall it, that it might be well to abolish the faculty altogether and resolve the college into a voluntary congeries of earnest, intelligent young men (for such we knew ourselves to be) intent upon educating one another! Age has probably sufficed to inspire doubts that this would have worked well—and as a matter of fact it would not have been suggested in any serious inquiry. But it was once eagerly debated by knots of young men who thought they could see beauties in itand it was good humoredly expostulated by amused professors that the faculty should at least be permitted to remain in town and possibly become educated themselves!

We are all much surer of our judgments at 21 than we are at 61 concerning the general run of things, most of all concerning what is the best way ot educating the young. But age has evidently learned that it may with profit turn in all seriousness to the actual students of the moment to ask what is their view, or whether a view exists in which a considerable majority concur, to the end that this be checked up with the views of other and maturer men everywhere, to" whom the problem is a matter of concern. It will, we think, be welcome to find that the president has invited undergraduate cooperation in this discussion as one of the primary essentials for shedding light. Certainly the alumni are not too sure what the College is trying to do, and very likely the students are not very sure either. But if, by getting together and threshing out the question amiably, we can arrive at some appropriate answer we may then know better how to go to work to do it.

We have at least come some distance since the days when Dr. Samuel Johnson trumpeted his inflexible doctrines of obedience to the constituted authority and roundly denied that students had any right to their own opinion. Possibly you recall the incident in which Boswell sought to defend six Oxford men who had been expelled for non-comformity to some college regulation—in some matter of religion. "Sir," said Johnson, "that expulsion was extremely just and proper. What have they to do at a University who are not willing to be taught, but will presume to teach ? . . . I

believe they might be good beings; but they were not fit to be in the University of Oxford. A cow is a very good animal in a field; but we turn her out of a garden." What would be this crusty philosopher's opinion today no one knows; but for a guess he would view with something akin to consternation the proposal that students be invited soberly to sit down with the doctors and point out wherein the system of education could be amended to the betterment of all concerned. If so, Dr. Johnson would be wrong—and most certainly would not admit it.

From all of which it is not to be imagined that the matter is left exclusively or even predominantly to undergraduate referendum. It is a matter in which the entire Dartmouth fellowship is to participate, assisted by a painstaking expert investigation of educational theories in this and other countries, which latter task is entrusted principally to Professor L. B. Richardson. When all the available material is assembled it may be canvassed by the college authorities and estimated as to what its various parts are worth. Out of it all may well emerge a clearer knowledge of our collegiate mission and of the best methods of fulfilling the same. It will certainly do no harm to talk it over, even if (to revert to Omar) we emerge by the same door wherein we went. That is very likely to be the. ultimate event, but the pilgrimage will not have been amiss.

In any case it is evident enough that conditions have altered in material ways since the earlier stages of college development. It is no longer a matter of educating a chosen few, who have sought college education for some definite, professional purpose, but rather of educa- ting the indiscriminate many who now seek college connections because that is the accepted thing to do. Is the service of this greater multitude necessarily different from that accorded a much smaller group, with the more definite aims which were usually manifested a generation ago? Of that we can feel but little doubt. The requirements are obviously very different—but thus far the colleges have rather drifted about with hardly an effort to ascertain what they were. College education in its present estate is a sort of Topsy, who has "just growed" without any plan. We have drifted away from classical moorings and have hardly as yet established new ones of any sort. President Hopkins has very sensibly concluded that it is time to straighten out the course if possible and determine, as far as may be, what is the port to which we should steer. God-speed, then, to every undertaking which has to do with the wise - solution of this problem, which at least is set before us in a tangible and definite shape instead of left in the customary tangle.

The original Dartmouth Green Ribbon

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHIRTY YEARS OF ALUMNI REPRESENTATION ON THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

May 1924 By James Fairbanks Colby '72 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1924 By F. L. Janeway -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN THE SEVENTIES III

May 1924 By Samuel L. Powers '74 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR RICHARD WELLINGTON HUSBAND

May 1924 By Charles Darwin Adams -

Class Notes

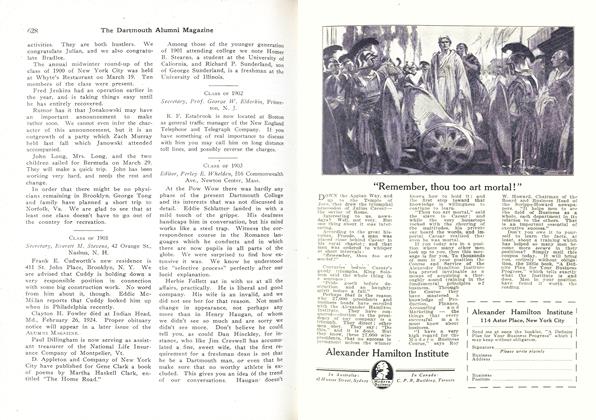

Class NotesClass of 1903

May 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

May 1924 By H. Clifford Bean

Article

-

Article

ArticleFRATERNITY CHINNING SEASON

December, 1911 -

Article

ArticleThe Russians Pay Up—in Rubles

-

Article

ArticleSound Bodies

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Article

ArticleStudent Researchers in Greenland

DECEMBER 1965 By GEORGE LINKLETTER '65 -

Article

ArticleProject Emperor

June 1992 By Nancy Davies -

Article

ArticleFor the Marines

March 1945 By Pvt. Robert G. Marotz USMCR.