Living conditions at Hanover in the seventies were very similar to those in other college communties during those years. It was before the advent of the telephone, the electric light, the automobile, and those other discoveries which have contributed so much to the comfort of living during the last forty years.

About one half the students roomed in the college halls, and the other half in private houses. Those living in the halls furnished their rooms and cared for them, but hardly in a manner that would have satisfied the taste of a good housekeeper. The only method of heating was by the stove, and the fuel was wood, which the boys bought of farmers who drew it into Hanover on sleds and wheels. The wood was in four-foot lengths, and was sawed by the students and carried up to the rooms. The only method of lighting was the kerosene lamp and candles, with now and then a German study lamp, which made use of lard oil, and compared favorably with any light for reading that has ever been discove red. The water system of that day was the old-fashioned well, to which was attached a wooden pump, which in the coldest weather refused to work until it was thawed out. The most famous and useful pump was the one located on the easterly side of the Common, directly opposite Thornton Hall, and supplied the rooms in Wentworth, Dartmouth, Thornton and Reed. The boys carried the water to their rooms in large earthern pitchers which held about three gallons. There were no bath-rooms in the halls, and so far as I know none in the village,—but that was true of all other New England college communities at that time.

Some years ago I listened to a speech at a Boston club banquet by a Harvard graduate of the class of '78. He was lamenting in a rather facetious vein the decadence of Harvard, due to the introduction of luxurious conditions of living, which he claimed would develop a race of weaklings. He said, "Do you know that every student at Cambridge has a bath connected with his room, and takes a bath every day ? In my time there was but one bath-room at Harvard, and that was put in by a wealthy New York student, not to be used for bathing but as a convenient receptacle in which to cool his wine." The method of taking a bath at Hanover in my time was by a large tin tub, which when not in use hung on a fixture on the wall of the sleeping room, and a large kettle, in which the water was heated upon the: stove. The rooms in private houses were furnished by the owner, but care, heating and lighting were provided by the students. The charge for rent at the College was entirely reasonable, varying from $7.50 to $lB.OO per annum to each student, and in private houses about double that amount.

Table board, the most important item in connection with living expense, was furnished by a method which had longbeen in use, and was paid for at actualcost. The method then in use was the formation of a voluntary association of some thirty members, who elected one of their number to fill the important office of "commissary," and he acted as agent for the association, arranging with the landlady to provide dining-room, service, and the preparing and cooking of the food, her compensation being fifty cents per week for each boarder. The commissary furnished all the supplies, and the landlady was entitled to use such part of the supplies provided by the commissary as were necessary for the support of herself and her family. These landladies usually had large families, and frequently entertained numerous visiting relatives for rather long visits during the winter months. When the club was once under way the commissary presented a tentative bill of fare, which was discussed in a parliamentary session, and amended in such form as to receive a majority vote of the members. This bill of fare became a fixture for the full term. After a few days we all knew exactly what was to be served at each meal during the week. There were no surprises and no disappointments. The club by vote determined what the cost of board should be, which varied from $2.75 to $3.25 per week. The situation of the commissary was not unlike that of a railroad management at the present time, he was bound to give satisfactory service at a stipulated price and meet the cost of operation. The commissary received his board for his services, but he earned it. He was subject to criticism and even abuse, not only from the members of the association but from the landlady and the people from whom he purchased the supplies. He never failed to show the wear and strain of his position, and only a vacation saved him from a complete breakdown.

There were a few select boardingclubs which catered to a limited number of plutocrats upon whom Dame Fortune had lavished wealth and an epicurean taste. Rumor had it that these sleek and rotund young gentlemen paid the enormous sum of $5.00 per week for table board.

When we examine the class pictures of graduates of fifty years standing we are impressed by the similarity of dress among the college men of the New England colleges. The tall silk hat was in use by the great majority of the students after freshman year. It was considered the proper thing to wear with any kind of suit, without regard to color or style. By quite common consent it was best adapted to a long black coat and grey trousers, but if worn with a light grey sack coat it caused no unfavorable comment. The tall hat was in itself a certificate that its wearer was a gentleman, and even though the hat was of an early vintage it rather increased than lessened its dignity, and indicated that it had been in the family for many years. A black string necktie was the constant companion of the tall silk hat.

This was the era of whiskers. There were but: few men in the American colleges fifty years ago who were so devoid of ambition as not to desire to sport a beard—especially side whiskers. The youth who entered college at fifteen was at a great disadvantage. He was still a boy, and not a man.

Athletic sports were in their infancy and of a limited variety. The old Association, or as it sometimes was called, the Rugby game of football, was played on the campus, and afforded an opportunity for one to- get more or less exercise outside of the winter months. The freshman-sophomore annual game was more of a fight than a game. The traditional prohibition against freshmen wearing tall hats and carrying canes was still in vogue, and its enforcement by the sophomores frequently led to serious clashes. President Smith's love of individual liberty was so intense that he insisted there should be no interference with the right of any student to wear any kind of hat and to carry any kind of walking stick. The class of '74 was forced to contend not only with the freshman, but the faculty, in its attempt to preserve a time-honored custom, and their ranks became so weakened by suspensions that they found it necessary to sign an armistice.

Baseball as an intercollegiate sport was adopted by Dartmouth in the late sixties. These were the days of underhand pitching, and the use of a lively ball, which produced scores frequently of fifty or sixty on a side. Dartmouth was defeated in the early seventies by Harvard by a score of forty to nothing, which under present conditions of playing would have been about equivalent to a score of four to nothing.

Dartmouth became a member of the Intercollegiate Rowing Association in the early seventies, and took part for a number of years in the rowing contests at Springfield and Saratoga. Her record was most creditable, but sooner or later she was forced from her practice ground by log driving down the Connecticut River, and obliged to withdraw from rowing contests.

During the senior year it was the habit of small groups of students to meet and discuss the various men of the graduating class, and to make prediction of the future which awaited them in the great world of affairs into which they soon were to enter. These predictions were sometimes correct, but in the majority of cases they were quite wide of the mark. We failed to estimate the cross currents of life which so often check and baffle real ability and high ambition. We also failed to consider and give due weight to the favoring winds and tides which frequently waft the man of mediocre ab.lity to a success and prominence which could not reasonably' be anticipated. Health, family, marriage, friends and location all play an important part in shaping the destiny of the individual.

I have always regarded Prouty of the class of '75 as the most brilliant-student of the seventies. I think his scholarship rank was the highest, but of this I am not quite certain. He competed successfully for all the prizes offered. He was in no sense a "grind," but when he did study he applied himself with great intensity. He was a student of positive opinions, which he expressed with the greatest freedom. He regarded the members of the faculty as his natural enemies, who were bent on interfering with his freedom of individual action, and he was constantly suggesting plans for radical changes in the administration of the College. While his tendencies were more or less mischievous he was nevertheless one of the best hearted and most companionable men I have ever known. If Prouty had remained in the general practice of the law my belief is he would have become one of the foremost lawyers of the country. Early in his professional life he became attorney for the Vermont railroads, and his marked ability in dealing with complex and intricate questions of law in its relation to railroad transportation suggested his appointment on the Interstate Commerce Commission, where he remained throughout the greater part of his life. He rendered a public service of great value, and labored for many years with tireless energy, receiving a salary entirely inadequate for the service rendered, and meagre public appreciation for his important service—but such is frequently the lot of the honest, able official who devotes his life to the service of his country.

Frank Black of the same class as Prouty became one of the most distinguished gradutes of the seventies. His college course was seriously interrupted by his enforced absence from his studies while engaged in teaching school in order to secure funds to pay his college expenses. Those of us who knew him best recognized his sterling qualities and force of character. He adopted the law as his profession, and settled in Troy, New York. He came forward rapidly, and after a few years was selected by the people of his adopted city to lead a reform movement to rid the city government of a notorious political ring. The people under Black's leadership won the city election, and this led to Black's election to Congress from the Troy district. Later he became Governor of the Empire State, and at one time was seriously considered for the Republican nomination for the Presidency. Upon his retirement from politics he removed to New York City, where he became a leader at the bar. He ranked with the best of the forensic orators of his time.

The career of John H. Wright of the class of '73 was in no way disappointing. He was a marvelous Greek scholar in college, and later in life became the foremost Greek scholar of his day.

Dexter Bigelow, who ranked the class of '73,—a class noted for its high scholarship.—became a lawyer, and has devoted his life to conveyancing,—one of the most difficult and intricate specialties of the law,; which requires its devotee to live the life of a monk, studying ancient records, and guaranteeing the accuracy of his conclusions, which the general practitioner is not required to do. Bigelow has become very distinguished in his specialty, but if he were the most famous conveyancer in the world our college trustees would never think of voting him even an A.M. degree. If he had entered the field of education or medicine the situation would have been quite different.

Joe Haynes was the leader and valedictorian of the class of '74. At first he took up banking, but later decided to devote his life to farming, and is a successful farmer in lowa. However successful the conveyancer and farmer may be thej' are not in the limelight of publicity, and yet at the same time they are probably rendering service quite as important to the community as that rendered by men in public life. They fail, however, to receive that recognition for service rendered which so frequently is bestowed upon others. in different callings.

I feel sure that no one ever pred icted the career that awaited Charles R. Miller of the class of '72. In college he was a jolly, rollicking fellow, never taking college life too seriously, and revealing none of those traits of industry and tireless application which made him later in life the leading American journalist, and in control of a great metropolitan daily. The traits of character which were so apparent in the later years of his life were not revealed in his college days, and yet he may have been conscious that he possessed the strength and resolution to accomplish a great service in his chosen profession.

I am reminded of Charlie Caswell, of my own class, who received little or no benefit from his college training, and did not receive his A.B. degree until more than twenty years after his class graduated. He studied law, located in Colorado, and became a distinguished citizen, and at the time of his death was a Justice of the Colorado Supreme Court. If anyone in college days had predicted that two members only of our class would become Justices of a State court of last resort, and that Caswell would be one, such prediction would certainly have amused us. Some years after graduation Caswell decided that it was in him to make a success of life, and he proved that his estimate of his own abilities was correct.

We all agreed that McCall, Parsons and Aiken were destined to achieve successful careers, and our prediction became true, but I doubt if anyone during college days predicted a distinguished career for Frank Streeter. He entered our class at the beginning of sophomore year as a transfer from Bates College. He was one of the youngest men in the class. He was quiet and unassuming, .and did not take any very active part in college affairs. He revealed none of those strong dominant traits of character which made him later in life a leader of men and a vital force in the affairs of the State and College.

Another example similar to that of Streeter, but even more exceptional, is that of Francis E. Clark of the class of '73. During his college days he was a quiet, studious youth, conscientious in the performance of every duty, and greatly beloved by his fellows. I doubt, however, if even his most intimate friends of college days ever imagined that he possessed that marvelous genius for organization, and those striking qualities for administration which have enabled him to organize and set in motion influences for the advancement of religion and social welfare which have extended throughout the Christian world. I feel sure that most Dartmouth men - will agree with me that Frank Clark has exercised a larger influence for the good of the world than any other graduate of the seventies, and that his fame is likely to be of a most enduring character.

It would be pleasing to comment upon a larger number of men who were at Dartmouth during the seventies, but space will not permit. The few I have referred to illustrate the difficulty of predicting during student days what this or that - boy is likely to achieve during his manhood -years. This rule, however, may safely be followed, that the high ranking student is more likely to achieve success than the man of low rank. There are two elements in the make-up of the high ranking student which play important parts in the world affairs—ambition and industry. Without these, large success is not likely to be achieved. The brilliant student with a mind of that quality which approaches genius is not likely to render important service in the absence of ambition and industry to accomplish a definite purpose in life.

During the seventies Dartmouth graduated nearly eight hundred men. They went into every state in the Union; they entered numerous fields of service; the undaunted spirit of Dartmouth was in their breasts; they sought no royal road to fortune and fame, but were content to do their duty as they saw it, and accept the rewards to which honest and conscientious toil are entitled. The love of the old College was in their hearts, and wherever duty called them they remained true and loyal sons of the old Mother in the Granite Hills, who had watched over them in their youth, and sent them forth into the wide world to render service to mankind.

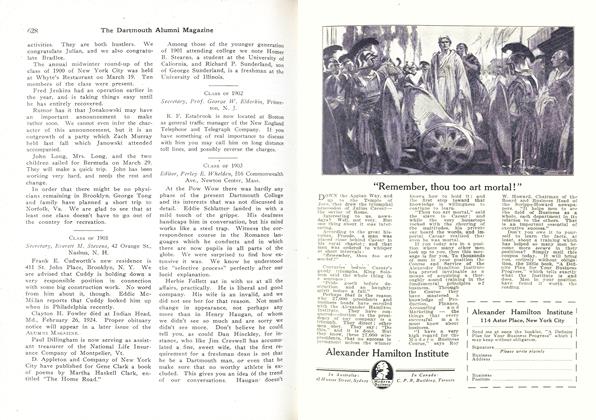

The new Kappa Kappa Kappa House was formally opened by a reception for the faculty April 20

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHIRTY YEARS OF ALUMNI REPRESENTATION ON THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

May 1924 By James Fairbanks Colby '72 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1924 By F. L. Janeway -

Article

ArticleIn the death of Richard W. Husband

May 1924 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR RICHARD WELLINGTON HUSBAND

May 1924 By Charles Darwin Adams -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

May 1924 By Perley E. Whelden -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

May 1924 By H. Clifford Bean

Samuel L. Powers '74

Article

-

Article

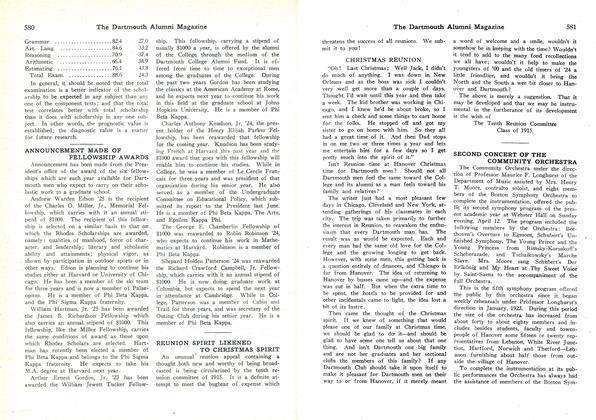

ArticleANNOUNCEMENT MADE OF FELLOWSHIP AWARDS

May 1925 -

Article

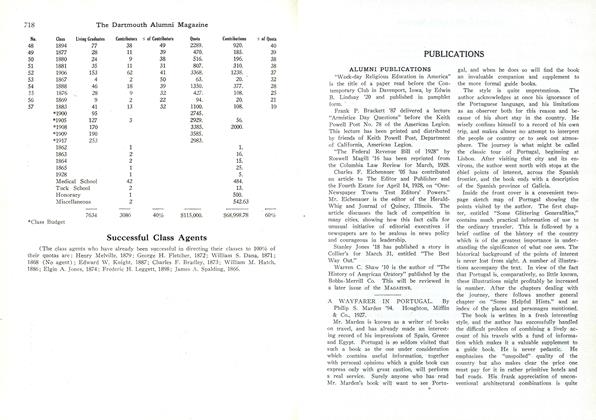

ArticleSuccessful Class Agents

JUNE, 1928 -

Article

ArticleTribute to Nick Sandoe '45

OCTOBER 1967 -

Article

ArticlePresidential Medal

SEPTEMBER 1991 -

Article

ArticleThe Job Outlook

April 1952 By C. E. W -

Article

ArticleMEETING THE PROBLEM OF COLLEGE ATHLETICS

June, 1911 By W. Huston Lillard 1905