in the history of Dartmouth College. It is pleasant to feel that there has developed no sign of. any retrogression from the position to which the College has advanced during the past score of years— a position in which it figures no longer as the "little college" referred to so feelingly by Webster, but as one of the greater institutions of the land in point of both physical size and moral influence.

There have beep, it is true, some indications that alumni should be on their guard against exulting unduly because of this growth and in an especial manner •should beware of overrating the virtues of expansion. One falls a rather easy prey to megalomania. To many of us it seems quite possible that we have reached the limits at which expansion remains a profitable thing—and consequently the point beyond which further aggrandizement might be a thing of disadvantage. Men will always differ as to the appropriate size of a college unit, and also ias to the advisability of seeking enlargement into the estate of a university; but unless we wholly misconceive the spirit of both the present administration and the majority of the alumni, the feeling predominates that Dartmouth as it stands today should remain a college, and further that to do so it must be very cautious about encouraging further expansion either in numbers or in scope. It is important, as always, not to start anything we cannot finish; not to set any pace we cannot hold.

And yet one sees the essential rashness of dogmatizing. One who had predicted, say 20 years ago, that Dartmouth in 1925 would muster over 2000 students surrounded by such an equipment as we now possess, would have been rated visionary, to say the least. It would have struck the alumni of 1900 as lunacy if it had been foretold that in 1925 their body would cheerfully raise in that single year, merely to piece out the college income, a sum exceeding $90,000. It is never safe to say what one cannot expect to do in such a case. Nevertheless there exists a growing sentiment that Dartmouth may have very nearly "got her growth" so far as concerns her scope and numbers, and should devote herself henceforward to maintaining, rather than extending, by a process which in the recent war was usually called "consolidating the position."

It is notorious that in such cases there operates a sort of law of diminishing returns, so that greatly enlarging the student body by no means implies proportionately increasing the college income to keep pace therewith. Not only does no student pay the full cost of his education, even with the tuition fees raised (as they will be a year hence) to $400, but also the steady increment of size entails a serious expenditure in the provision of adequate dormitory space, lecture rooms, laboratories and the like. It has also to be remembered that as the student body increases in numbers there must be some inert-ase also in the teaching force—and at the same time there is pressing the problem of providing for the faculty which we already have a compensation sufficient to enable us to keep the good men whom we train up from youthful instructors to mature professors. At present the demand for such men in other colleges leads to repeated losses from our own force. It is therefore apparent that what Dartmouth now needs is, in colloquial parlance, "to catch up with herself." She has grown almost too fast, if anything. Perhaps she is large enough already—and most certainly she requires a breathing space in which to enable a harmonizing of her resources to meet the enhanced demands made by a student body as large as that now to be regarded as averaging slightly over 2000 young men.

Distinctly encouraging is the fact that one hears more and more comment from the alumni in all sections of the country on the pressing need for a library—the great project of the immediate future. That is the one thing we are all agreed on. The obvious disproportion between our gymnasium and athletic field equipment and that devoted to the housing of books cannot be permitted much longer to endure. One finds the library just where it used to be a generation and more ago—in Wilson hall, of which we were once so proud to say that it housed 70,000 books and was lighted by the most expensive gas in the world. It did passably well for a college numbering 400 students—including the "medics"—but it is ridiculously insufficient for the satisfaction of 2000 students and a faculty of many times the former size.

To such as comment on this need it may be reassuring to state that the President and Board of Trustees are as keenly alive to the necessity of this thing as any one can be and have the matter quite as much at heart. It is one of the perplexing problems only because of the magnitude of' the expense involved. At a time when the alumni are annually required to do so much for the maintenance of the Alumni Fund it is hardly feasible to make the erection of a new library the subject of an additional canvass, and one must be on the lookout for other means which, we are Confident, will be found. There is even the bud of a beginning in the form of tentative designs for such a structure when it shall become possible to set about its erection—and that, in the nature of things, can hardly be postponed for more than a year or two. It is a project which really cries aloud for consideration.

More or less interest will be felt in the working of the expedient adopted with reference to daily chapel services—no longer compulsory as of yore, nor entirely non-existent as they were during the greater portion of the past academic year, but voluntary for such students as may care to attend them. One hazards very little in predicting that Rollins Chapel as now constituted will hardly require further enlargement, of course. It is one thing abstractly to approve of compulsory chapel and another thing concretely to betake " oneself thither every morning when compulsion is removed ; so that many a student who might vote in favor of chapel services may be a rather infrequent attendant, in common with those who heartily welcome the abandonment of the ancient requirements.

There is bound to be a general doubt whether voluntary chapel is worth while, on the part of those who regret the necessity of abandoning the old rule by which we all used to go. Many will say at once that it ought to be compulsory or nothing. Nevertheless it is well enough to make trial of an expedient which offers an opportunity for such as are religiously and devoutly disposed, even though few by comparison with the entire body of students and others. At least those who attend will be there because of an appropriate attitude of mind, which was one of the sources of indictment against the compulsory brand so long prevailing.

It is possible that the most telling argument against obligatory morning "worship"—to give it the name which it too seldom merited—lies in the impossibility of housing in one chapel so numerous a congregation. There has always been doubt of the pertinence of the complaint that modern youth derive no spiritual solace from their few minutes' association with Scripture reading, the singing of a hymn and the hearing of a public prayer, chiefly because of the suspicion that the youth of a century ago derived equally little if the truth were known. It is probable that youth, like human nature in general, experiences very little alteration with the lapse of years. Conscious reverence was certainly not too common with the rank and file of us in the late 'Bos and early '9os, and one recalls the hurried survey of textbooks in the gloom of that never-too-well illuminated edifice which engrossed so many who, to all seeming, were bowed respectfully in attitudes commonly rated consonant with the devotional spirit. In a word it is open to question whether as a devotional exercise morning chapel was ever of much worth from the viewpoint of the multitude who went because they had to, whether in the 19th century or the 20th, and very possibly in the 18th as well. But it served its purpose. It got the college up in the morning and started it right. The men derived little immediate spiritual benefit, perhaps, but certainly they suffered no harm. It served the ends of discipline—and many there acquired a bowing acquaintance with the classic Bible who otherwise might have had little or none.

In these days it is difficult to discover what, exactly, is "religion"—even in one's own personal case, when unembarrassed by the inquisition of others. It has always been peculiarly true in the period of youth, when one is putting away childish concepts and feeling about for others, that the average boy suffers through a twilight zone of what he prides himself is downright unbelief in anything religious. The mention of spiritual things commonly finds young men shamefaced and reticent. The beauty of holiness is usually appreciated more keenly in later years, and it takes time for all of us to perfect a satisfying theory for ourselves. Youth resents being preached at, though sorely in need of preachments. One somehow feels that it is a pity to lose all touch, as so many do, with the outward formalism in which we dress our little kernel of faith, through the abandonment of such contacts as enforced attendance in those years at chapel or churchly services used to entail. From this, of course, the youth devoted to the Roman Catholic church suffer but little if at all. Those reared in the Protestant faith suffer much—and it is all too rare to find any clergyman with the power of arresting the attention of young men at that stage of their development, when the universe is so terribly egocentric, and where one's childish notions of God are coming to appear untenable. Daily contact with the purely formal side of religion no doubt hastened reaction in many cases, or intensified it for the time being; but it is to be doubted that it did any permanent harm and one inclines to the belief that despite all appearances it did some good.

But all this is aside from the practical fact that compulsory morning chapel at Dartmouth is physically impossible, whether it was or was not morally profitable; because the chapel isn't big enough for so many students and cannot be made so.

The address of President Hopkins to an entering class of approximately 625 freshmen, at the opening of the College in September, was as always a stimulating utterance, although devoid of anything sensational to arrest the special attention of headline readers. The occasion must always be heavily charged with inspiration to any competent educational leader; and the desire to awaken in these new-comers something of the zeal for learning without which, on the part of the taught, the teacher labors in vain, may be easily appreciated. It amounts to a sort of inverted baccalaureate—not a sermon preached to those about to become bachelors of arts, but one addressed to neophytes at the threshold of the shrine of learning. As such, although it is not customary for the speaker to take any specific text, a text is appropriate to it; and in the instance before us the clear implication was that the adjuration in the Book of Proverbs, "get wisdom; and with all thy getting, get understanding," fitted the case to a nicety.

The freshman has before him four years such as he will never again enjoy. The opportunities which lie open during one's college course are for most of us never duplicated again. With all the exacting routine there remains much leisure ; and the question is simply of turning both the routine and the leisure to the maximum of account, so that at the close of the four-year period one may feel a reasonable satisfaction which will increase, rather than diminish, as one obtains a perspective view. For too many of us, alas, the satisfactions which we may have felt on Commencement day tend to diminish. Always the burning wish is to inspire those just setting out to guard against that possibility; to be warned by our experience.

"The fulfillment of the educational ideal can only be attained," said the President, "through the presence of an eager, intellectually serious, and industrious group of men as students within the college. " This has been said before, but it cannot be said too often. It is imperative that teachers have the power to interest their students, but they can seldom or never do this efficiently unless the students on their part are honestly desirous to be interested. The President's surmise that the increased numbers now seeking admission to the colleges do not indicate a like increase of zeal for education, is entirely justified. Going to college has come to be so widely regarded as the customary and natural thing for a boy that it is "no longer a romantic adventure" and no longer brings with it the old-time solemnity of recognition for the available opportunities. Perhaps the pithiest saying in Dr. Hopkins' inaugural this year was that "the old-time desire for the distinction of a college degree has been replaced in the case of many a man by the desire to avoid not having one." Men go to college in amazing numbers, not because they hunger and thirst after culture beyond what was true of their elders, but because it is the thing that every one does. A certain indifference arises out of the very customariness of it, from which it is desirable to awaken the student. Moreover the student must do most of this awakening himself. One may sound the alarm-clock—but the man himself must throw back the bedclothes and spring up to dress in the garments of intellectual day.

There was a reminder, too, of the President's former remark about an "aristocracy of brains" in his renewed insistence that such an aristocracy is a fallacious thing when it starts with the notion that brains are the "exclusive possession of any formal group to be defined by birth, wealth, social station, or previous association with formal institutions of learning. ... It is a theory which can be justified only if brains are to be paid deference wherever found." All the time the aim must be, not merely to get wisdom, but to get understanding sufficient to apply wisdom to life, to society, to politics, to whatsoever activity may arise. One must somehow learn to know the weeds from the wildflowers in the field of ideas—to know the nutritious from the noxious. In fine, it is a man's job, this being educated—and it is put up to immature young fellows, few of them more than 18 and many less than that, who naturally have not the appreciation that their elders have of the opportunities that lie before them for the taking. Si jeunesse savait! Si vieillessepouvait! If only we could go to college at 18, with all that eagerness to know which we feel at 50—because, when too late, we wish we had wanted to know! A fortune, or at least high fame, awaits the discoverer of some intellectual thirstprovoker—something that shall not merely lead the souls of young men to the waters, but make them eager to drink deep of the Pierian spring. We have seen the numbers of college students increase beyond all expectation, but without a corresponding spread of the zeal to partake. Most, one fears, are there because it is so pleasant to be there, rather than because of any .raging fever to assuage. One sips—much as one takes the prescribed doses at a Spa of water which, as Samuel Weller remarked, has the taste of warm flatirons in it—instead of drinking eagerly, like one athirst. There's all the difference in the world between the attitude of the perspiring haymaker at the old oaken bucket, and the attitude of the holiday-maker at Bath, or Bad-Nauheim. The one drinks because he has a genuine craving for the water; the other because he is told it is good for him and because it is the custom of the place.

It might almost help to prohibit this intellectual beverage. At all events the efforts to prevent "Godless" colleges from teaching "evolution" appear to have made courses in it among the most eagerly sought by otherwise indifferent students; indeed, since the trial in Tennessee there has been an expression of curiosity in irreverent quarters as to "what they're going to call the fellows who bootleg their biology." However this last can hardly be regarded as seriously appropriate comment on the very big, very insistent, and very vital problem which Dr. Hopkins has constantly before him and to which, with tireless energy and inexhaustible cheerfulness, he annually recurs in bringing before the entering class a vision of its proper aims and purposes.

An indication of Hanover's Saturday popularity

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICAL FITNESS

November 1925 By W m. R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Article

ArticleUNDERSTANDING

November 1925 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1925 -

Article

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1929

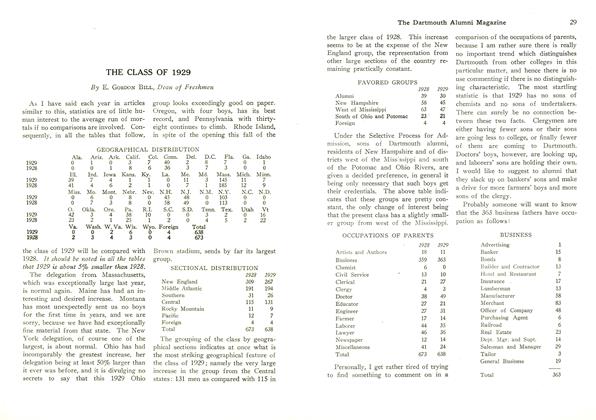

November 1925 By E. GORDON BILL, Dean of Freshmen -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November 1925 By Franklin Mcduffee, Frank Maloy Anderson -

Article

ArticleSOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ASSOCIATION

November 1925

Article

-

Article

ArticleProfessor Burton Appointed Justice

August, 1911 -

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB AND HOSPITAL BENEFITTED BY C. H. GREENLEAF

August 1924 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Club Luncheons

March 1949 -

Article

ArticleSecond Trustee Term For Harvey P. Hood

July 1950 -

Article

ArticleOverruns

May/June 2012 -

Article

Article30TH CARNIVAL TO BE A BIG BIRTHDAY PARTY

February 1940 By Peter Glenn '41