111 A Report of Progress, Second Semester, 1924-25.

THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE for February, 1925, contained an article stating problems of physical fitness as they appeared in the results of an examination gwen the members of the class of 1928. This was followed in May by a report of the work m this class of 1929 Further accounts of similar work conducted by Dr. Emerson at the of the college year and indicates the lines of action to be undertaken wrth the incoming class of 1929.' Further accounts of similar work conducted by Dr Emersoin at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology will be found m the M. I. T. Publications, Volume 60 No. 11, pp. 11-22 and in the Woman s Home Companion for July and September, 1925.

In our report which appeared in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE for May it was shown that 60 underweight men who entered upon our program for physical fitness at the beginning of the college year for the most part either losing weight or failing to gain, had succeeded by the end of the first semester in making an average gain of 295% of what is expected of an average, healthy, sixteen-year-old boy in the same period of time. This amounts to a rate of 24 pounds a year. On the same basis 89 men who were under care during the second semester show an average gain of 313% for the period spent in the physical fitness classes—a yearly rate of 25 pounds.

Our first efforts at Dartmouth were with members of the freshman class. Results secured with them should give returns during the entire four years of their college course. Then, too, it is felt that the freshmen have many difficulties to meet and, for this reason as well, they should be given every advantage possible early in their course. Later in the year a special class was organized for upper classmen. It has been our expe- rience that the men who deliberately choose to enter upon a program for bettering their physical condition rank higher on the average in college grades than do their fellow students. For like reasons the class composed of older students with greater experience made the best gain accomplished during the year nearly double that made by the first year group.

Again in a class composed of underweight freshmen athletes who knew that to gain in weight was the first and most important step to be taken in their training in order that they might excel in the various sports, greater progress was made than appeared in groups which had less immediate incentive to gain. This class gained at an average rate of 464% —a little less than that achieved by the upper classmen and a little more than an annual rate of 35 pounds.

Our work has been for the student body and was supposed to concern the faculty only in so far as they are interested in the welfare of the students. Some of the faculty, however, when they saw what could be done by means of the program went in for it themselves. One professor had always supposed that he was "naturally thin" and could not attain the weight which he had good reason to know would afford him better health than was possible as long as he continued to be seriously underweight. For ten weeks he maintained a gain at an annual rate of 56 pounds and for the 18 weeks he was on the schedule his gain was at a yearly rate of 40 pounds.

Another member of the faculty has been compelled this summer to take special treatment which, ordinarily, would pull one down in weight. He has found that the resistance built up on the basis of the physical fitness program has enabled him to go through this experience not only without loss but with a net gain of five pounds. A year ago he would have declared that it would be impossible for him to make any gain even under the most favorable conditions.

Health improvement in members of the staff must mean more efficient direct service and indirectly it must prove valuable in bringing about better relations between students and teachers. An illustration of failure to understand the student's point of view came to me last winter in the case of a young man who was under my care. He is in attendance upon a large university. The great social event of his junior year involves festivities lasting until morning. This brought the student back to his room at five o'clock when he was compelled to get to work at once without rest or breakfast, preparing for an examination set for members of his class at 9.30 by a professor who had full knowledge of the situation and full power to adjust the time more reasonably if he had been alive to the best interests of his students.

The influence of the Dartmouth work reached even the office staff. One private secretary put herself on the program and maintained for 14 weeks a gain that in a year would have amounted to thirty pounds.

Another by-product of the work with the students was a meeting called of principals, teachers and others interested in the public schools of Hanover and neighboring towns at which the application of the program to the needs of children was presented. As a result of this meeting three classes were carried on efficiently during the year in the Hanover schools. A number of the children in the classes were from the families of faculty members and their improved condition helped to arouse the interest of their parents and has thus helped further the physical fitness work in the college.

Much stress has been laid upon the class features of the physical fitness program. A young man will see his own needs and possibilities much more effectively in the light of the problems and progress of others who are in like condition than he can deal with them alone. We have found, however, that the competition and suggestion factors can sometimes be accomplished most satisfactorily in small groups meeting more informally but at regular intervals. An experiment in this direction has been made at the office of the executive secretary of the department. Fourteen men dealt with regularly in this way have made gains averaging 302%—an annual rate of more than 24 pounds. During the year more than 200 men came to the office for weighing and for advice concerning their health.

Fairly definite records were secured on the attention given by men in the physical fitness classes to requirements in the way of rest periods, extra lunch periods and the keeping of diet books. The following table shows the results of a comparison of marks given for meeting these conditions:

RATE OF GAIN

Marks "excellent" and "good"

Rest periods Lunch periods Diet records

150% 125 145

Marks "fair" and "poor" 109% 65 92

This showing would indicate that the men with the higher marks for these requirements made from 50% to 100% better progress than was accomplished by those who did not follow out the program so adequately.

The machinery was not available for taking extensive records of weight and height for all members of the freshman class in order to be able to show the progress made during the year. Two records, however, are available for 427 men not under our special care and the next table compares the status of this group in the fall with that shown in May:

DISTRIBUTION OF PHYSICAL FITNESS GROUPS Fall weighing Spring weighing

Obese Safety Weight Borderline Underweight

4% 54 21 21 100

6% 53 23 18 100

These figures indicate that there has been no real improvement in weight conditions among these 427 men not in physical fitness classes. The safety weight group and the underweight groups have varied by only two per cent. An actual increase of 50% has occurred in the obese group, so that the only increase in weight has come to students who were harmed by it.

The 427 men just discussed did not include any of the men who were in the special physical, fitness classes. A comparison of SO underweight men who were members of these classes with an equal number of those who were also underweight but not in classes shows that those who were following the physical fitness program gained four times as much as did the fifty who were also underweight but were not under care during the year. It is interesting to note that according to the measurements taken by the Physical Education Department the former group also made 150% of the gain in height accomplished in the same time by the non-class fifty. In order to see whether the gain in weight given above could be accounted for by a few men in the classes making large gains a further comparison was made of the twelve best gainers in each fifty but the superiority of the physical fitness class men was less for the large gainers than for the entire group.

A comparison of the 89 men who were in physical fitness classes with the 427 not in classes shows that the former made twelve and a half times as much gain in a shorter period of time.

A study of the distribution of college grades for both semesters with reference to physical fitness groups showed that the underweight men received twice as many low grades—less than 1.0—as the average of all the freshman class. They also received three times as many very low grades as were found in the optimum weight group—the men ranging from average weight to ten per cent above average. In the proportion of highest grades given—2.s and above—the underweights ran below the average and the optimums above the average. As seems always to be the case the obese men ran low in high grades and had more than their natural share of low grades. For comparison a similar study was made of the school grades given 500 children in an elementary school in Portland, Maine. The relative proportion of low and high marks with reference to obese, optimum and underweight condition was much the same among the young children as appeared among the Dartmouth freshmen. This similarity indicates a fact of great significance in our whole educational program.

The difference between 1.2 and 1.8 in grades to a college student is considerable, yet a comparison of the underweight men who lost weight from September to May in the class of 1928 with those who gained weight in the same time showed this difference of more than half a point in favor of the students who gained weight. A similar but slightly smaller difference appeared in the records of the men who were in the borderline zone—underweight but less than 7%.

It must constantly be borne in mind that gain in weight is not the chief object of our work but it does offer the best single measure of improvement in physical fitness. It is practically impossible to get a student to gain steadily in weight without finding the causes of his bad condition and removing them.

Statistical statements offer valuable measures of results as far as they go but they are only one section of any important study of human life. Our chief concern is to raise the level of physical fitness during the growing period, and the central problem in this undertaking is the identification of various significant types which make up the large debit group of the physically less fit.

Experience with about a hundred members of the class of 1928 at Dartmouth indicates that those who enter college below par physically are easily grouped into three classes. The first of these is made up of medical cases. They have physical defects which have been overlooked or neglected. The majority of them, about 60%, are suffering from obstruction to breathing—inflammatory conditions of the nasopharynx or accessory sinuses—which must be corrected in order to enable the student to meet the requirements of college life in comfort and safety and to go out into professional or business life with adequate health. These men are not "free to gain" and while they get on fairly well under favorable conditions of life they easily fall to a lower plane of health or even fail utterly when they become subjected to any unusual mental or physical strain. Any strenuous activity on their part means an over-expenditure of energy which may lead to further loss of weight and health. They deserve sympathy for their condition. Often they are men of the highest scholarship. Many of them are suffering from toxemia. Their defects have not been discovered because the medical examinations given them have been made from the standpoint of disease and not with reference to their physical fitness.

An example of this type is Student E who was found to be 39 pounds—26% under the average weight for heightand suffering from seven physical defects. He had delayed entering college until his health would make success more probable than was the promise when he finished preparatory school. He had been in bed at one time for weeks because of spinal trouble. A course of strenuous treatment had been followed for four years. The most eminent specialists had been in charge of his case. There was no doubt but that medically all had been done for him that was possible but he had a confirmed idea that he could not take milk, eggs and sweets, yet by April he was able to eat all of these provided he rested an hour before his heavier meals. He had been certain that he could not gain because he had tried for years to do so but always without suc- cess. He said, "I think the class will be good for me but you must understand from the start that I cannot gain in weight." His extra lunches started with malted milk and a single cracker but in a short time he was able to take from 500 to 800 calories at each extra meal.

Fortunately the gymnasium provision recognizing rest as a substitute for exercise for those who required it enabled him to take the time needed to reduce his over-fatigue. As soon as he had surplus enough to profit by cross country walks these were taken but kept within the limits of over-fatigue. In the first eight weeks he gained eight pounds despite a loss of two pounds in November from the strain of examinations. More examinations in December and in January ran down his weight four pounds. By April he had got one pound beyond his high record in December but at the end of the year another bout with examinations was pulling him down again. His college marks for the year averaged 3.6.

The second group have what may be called "low health intelligence." Their greatest need is to have their 24-hour program of activities and their food and health habits checked up, and a more rational way of living worked out with them. When this is done they are soon on the road to recovery. They are suffering from a very common form of ignorance and offer the least difficulty in bringing about a better condition of health. An example of this type was student F. He was "free to gain" both physically and socially. He was pounds—6%—under average weight for height. Like the medical case just cited he did not smoke. His hours of sleep were good. The year before entering college he had lost 17 pounds as a result of over-training in running. He was out for cross country running and also for cabin and trail. Instructions concerning regular breakfasts and extra lunches were followed faithfully and greater care was taken to avoid overdoing. At the first it was hard for him to get his pace and a thirty mile walk taken one week-end with the loss of some breakfasts on his return ran his weight down nearly three pounds but at the end of 22 weeks from the middle of Noverber he had gained 15 pounds despite slowing up and actual losses due to the strain of examinations at various times. Possibly the most significant sign of his improved physical condition was evidenced by a gain of three pounds duringa hike of 170 miles taken in April. His gain was at the rate of nearly fifty pounds a year. His college grades averaged over 3.0 for the year.

Members of both groups I and II may require considerable training in habit formation after, in one case, the physical defect has been removed and, in the other, needed instruction has been given. None of these men, however, present anything like the problems which appear among the members of the third group. These are the men who fail in maintaining adequate standards of physical fitness chiefly because of lack of proper control. They have been "spoiled" children and at college they reveal themselves as "spoiled" young men. It is these men who "kick" bitterly at whatever food is furnished them. They are "down" on everyone who tries to hold them up to proper standards of work or sport. Their day's program is regulated by their desires and pleasures. They omit breakfasts, try to get out of this or that requirement. They are often under suspicion but usually are shrewd enough not to be caught in anything tangible that can be used against them.

They are not the material from which real Dartmouth men are made. They are an exotic group and the earlier they can be identified and either changed or removed the better for the college. They have been spoiled by one or both "spoiled" parents and come to college already past masters in the art of getting their own way. They are quick to discover what is expected of them and when they wish to do so can play up to the authorities with such charm and success as to help to confirm them in the belief that there is nothing in life but the attainment of their selfish desires.

Often they are not found out until they have made their fraternity or achieved some college honor usually extra-curricular. Examples are not wanting every year in football, college publications, class elections and other social situations in which they demonstrate that their whole scheme of life is self-centered and directly contrary to the ideals and the spirit in which the college was founded.

Such men are the problems not only of the college but of society in all its aspects. They are like an infected member of the human body which calls for diagnosis and prompt treatment in order that life itself and what is worth while in life may be saved. When once they have been given an opportunity to see themselves as they are and they still fail to accomplish a right about face, the sooner they are returned to their parents the better it is for the college, however bad it may be for the parents. In justice to this group it should be added that a certain number of them need only to be brought up against factors which perhaps for the first time in their lives they cannot control to enable them to see themselves in a better light. These few profit at once by firm handling and develop social qualities which may bring them up to normal condition of social relationship and of physical fitness.

When the facts disclosed by our social examination concerning four such men were presented to the college authorities it was at once said that three out of the four who had been given "another chance" would have been "separated" at once had these data been available when the decision had been made. Men who have been so unfortunate as to have become incorrigibly "spoiled" are among the most costly liabilities from which a college has to suffer. A wise administrator remarked of one youth of this type, "If we had known him for what he really is we would have made money by presenting him with a check for a thousand dollars and sending him on his wayanywhere but here!"

In a group of eight men who were eventually "withdrawn" from college seven deserved zero as a grading in "control." Their "health intelligence" based upon grades for control, reasons for over-fatigue, food and health habits averaged 43 on a scale of 100. Seven were physically not "free to gain" largely because of lack of "control." When we turn to college grade records we find that the eight averaged only 0.8; at the end of the first semester. Four of them were in the lowest decile class— 10; two were in class 9; one was in 7 and one in 3.

These men were reasonably objects of special inquiry from at least four points of view. It was important to the college to secure decisive data concerning them as early in their course as possible. It is not commonly the case that men of this type are free from suspicion but the authorities naturally are slow to act in the hope that they may be proved wrong in the impressions which have early been formed. The physical fitness work with its accurate health diagnosis and its well supported health intelligence quotient substantiates the charge of undesirability against the student under question and promptly provides the needed point of attack to remedy the difficulty.

An illustration of this type may be found in the case of Student G who was 10½ pounds—7%—under average weight for his height. He was "free to gain" but his "health intelligence quotient" amounted only to 15 on a scale of 100. He had been underweight since the age of twelve. His present poor condition, according to him, was entirely due to life at the college. He was unable to eat the food provided for him. His appetite was "finicky." He had been at the Commons for breakfast not more than four or five times up to the middle of December. He smoked IS to 20 cigarettes daily. Bed hour came at 11 or 12 o'clock and he got up as late as possible in the morning. It was not strange to find that his stomach was upset, that he had frequent headaches, and that he has "a cold all the time." He drank both tea and coffee daily—took only coffee and toast for breakfast. He ate much candy between meals and washed down his food with liquids. He was a restless sleeper, much constipated. During the holidays he was up all of four nights and out late every night. He also ate no breakfasts although we had especially requested cooperation in this matter while the students were at home. At the end of the semester he had carried out practically none of the suggestions which the other men were following to their great benefit. To attempt to re-educate and to make Dartmouth men out of such materials is like attempting to make bricks without straw.

Space does not permit complete medical reports on the various cases. A single instance will illustrate the medical significance of the work in physical fitness. A freshman on entrance was found to weigh only 112 pounds when the average weight for his height is 148 pounds. This extreme deviation of 22% from the average led to very careful special examinations which revealed a serious condition of diabetes calling for immediate removal from college for necessary treatment. The student had been very much concerned about his studies and was giving six hours a week to a single extra-curricular activity.

In our article in the May issue much detail was given concerning the causes of loss in weight and the diagnostic methods used to get at these fundamental causes. If space permitted it would be interesting to present more of this concrete material. There is, for instance, the case of the youth who said he was "all done out" whenever he had been through a heavy gymnasium period but who learned how to get himself into condition so that he was able to report that later on when he had finished one of these periods he "felt fine." There are cases of men who, knowing that they were about to incur special strain, came into the physical fitness classes to attain "optimum weight" although they were already near the average. Another man had found himself feeling miserable all the time and the year before had ended with a loss for him of ten pounds. The physical fitness class training this year has given him a gain of 269%—more than a rate of 20 pounds a year—and at no time had he lost any weight. This year had proved to be for him one of satisfying health.

But the successes must not lead us to overlook the great amount of work still to be done. The program has been carried on of necessity under modifications that must always be made to meet the conditions of an organization in full operation. One meets certain regulations and rules, innocent enough in themselves, but which have been brought about with little consideration of health necessities. Their effect is at times appalling. When one sees, for instance, the plateaux and depressions in weight lines at examination times, the losses due to social strain for which no margin has been provided, the beginning of a down hill course for a man in some childish initiation rite from which he has failed to make recovery during the rest of the year—such experiences as these lead one to desire that faculty and students alike may come to a more rational view of what constitutes worth while college life and may work to do away with causes of waste in the interest of greater enjoyment and efficiency.

What we have done is thus far only an entering wedge—the college program is already more than full and only minor adjustments have been possible. A very evident need is a scheme of accurate health diagnosis. Then we must make sure that the college program can justify the requirements it makes.

Among the advances already made are those connected with higher health standards for athletic teams. So far as we know the success of this year in getting through a football season without having a man go stale is unusual if not unprecedented. The changes concerning "chinning season" will no doubt prove to be off even greater significance than we can now see them to be. It is something of an absurdity to go as far as is done in carefully regulating the conditions of academic work without giving more attention to extra-curricular occupations. Some scheme which evaluates this large sector of college life and takes account of other interests and adequate health possibilities is one of the contributions due from Dartmouth to college life in general.

Along with this development must come greater concern for what is a fundamental requirement for health—adequate food served attractively with provision for sufficient time for enjoying and profiting by it. Each meal should be an opportunity for relaxation and recreation rather than, as is still too often the case, a period of hurried attention to a begrudged necessity which cannot be completely ignored but is given inadequate attention and consideration.

With these adjustments must go full consideration of examination requirements which have been shown to be demanding and getting their many pounds of flesh. We must seek such conditions as appear in the Academy at West Point where the strain of achievement is certainly not light but where the day's program is properly regulated and men go out well seasoned and trained to be physically and mentally fit.

In the carrying on of this work acknowledgments are due, first of all, to President Hopkins for his personal interest in the work itself and for smoothing out difficulties through the help of his remarkable college organization; second, to Dr. John W. Bowler in whose Department the work has been carried on, not only for his personal service in conducting two of the classes but for making many adjustments in his course to make the work possible; to Miss Florence Taylor whose enthusiasm and tactfulness have been of the utmost value; to Dr. Howard N. Kingsford who has placed at our disposal his most excellent records; to Mr. Frank A. Manny who has spent much time in correlating the different factors through his keen interest in this study; and also to Dr. Elmer Carleton of Hanover and to Dr. Harold Tobey of Boston for special nose, throat, and sinus examinations.

SUMMARY

I. Of 645 men entering Dartmouth College in the fall of 1925 3% were obese (20% or more above average weight); 30% were seriously underweight (7% or more under average weight for height) ; 25% were underweight but less than 7%; 42% were within the range of a safety weight zone.

2. A comparison of the weights of 427 men not including those in physical fitness classes taken in the fall and again in May shows practically-no gain in weight for the group as a whole except that the obese group increased 50% in numbers.

3. 60 first year students during the first semester of 1924-5 working on a special physical fitness program made an average gain in weight of 295%* of what is expected of a boy of sixteen—the last year of rapid gain. This amounts to an annual rate of nearly 24 pounds. 61 freshmen and 28 upper-classmen during the second semester gained at a rate of 313%. Individual cases ran up to the remarkable rates of 1000, 1200, and 1800%.

4. The best results were secured with upper classmen (476%) and with a group of athletes who were.required to attain certain physical standards before competing in athletics (464%).

5. For the entire freshman year of the Class of 1927 the obese group showed the lowest percentage of illness from nasopharyngeal causes; the underweight students had twice as much naso-pharyngeal illness as the optimum group. About 40% of the students were absent for illness during the year, losing an average of about five days for each case.

6. The chief obstacles in the order of their effect as measured by loss of weight were (a) grouped examinations, (b) chinning season, Carnival, and vacations, (c) competition in athletics and other extra-curricular activities.

7. The 89 men who were in physical fitness classes gained on an average 12 times as much as did the 427 not in classes in a longer period of time.

8. 50 underweight men in physical fitness classes gained four times as much as 50 underweight men not in classes. The former group also gained 150% in height as compared with the latter group.

9. Men who were "free to gain" made nearly double the gain in weight accomplished by those who deferred recommended nose and throat operations.

10. The men who observed late hours made nearly 100% less than the average for the entire group.

11. Students receiving marks of excellent and good for carrying out directions as regards rest periods, extra lunch periods, etc., gained from 50% to 100% more than those 1 who received marks of fair and poor.

12. Tobacco users averaged nearly 50% less gain in weight than the average made by non-tobacco users.

13. In a group of eight men "withdrawn" from college seven deserved zero in control and their average "health intelligence quotient" was 43 on a scale of 100. Seven were physically not "free to gain." The average college grade received by them was 0.8. Four of them were in the lowest decile group (10), two were in group 9, one was in 7 and one in 3.

14. The underweight men not in physical fitness classes who lost weight during the college year averaged .6 less in college marks than did those who gained weight in this time.

15. For both semesters the underweight men had twice as many college grades of less than 1.0 as the average of all the class and three times as many as were found in the "optimum" weight group—namely, those ranging from average weight to 10% above average. In the attainment of grades from 2.5 up the underweight men ran below the average and the "optimum" group ran above the average.

16. The obese men—20% or more above average—ran below average in high college marks and above average in low marks. They showed twice as many low marks and less than a third as many marks of the higher grade as were given the " optimum" group.

STUDENT E—A Medical Case Illustrating the helpfulness of the physical fitness program to a student with a fine mind struggling against heavy physical handicaps and the strain arising from college examinations.

STUDENT F Illustrating the failure of early faulty methods in training for "Cabin and Trail" and later the successful results accomplished by better methods growing out of improved health intelligence.

Medical Consultantin Physical Fitness at Dartmouth College.

*These men were for the most part either standing still in weight or losing weight at the time they began work on our program.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleUNDERSTANDING

November 1925 By President Ernest Martin Hopkins -

Article

ArticleHere Begnneth another year

November 1925 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

November 1925 -

Article

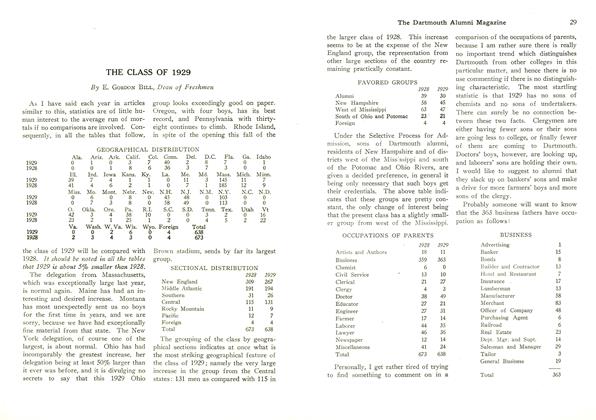

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1929

November 1925 By E. GORDON BILL, Dean of Freshmen -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November 1925 By Franklin Mcduffee, Frank Maloy Anderson -

Article

ArticleSOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ASSOCIATION

November 1925

Article

-

Article

ArticleREQUIREMENTS FOR A. B. DEGREE

March 1912 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF THE 1913 AEGIS SHOWS RE FINANCIAL SUCCESS

-

Article

ArticleFive Join Faculty

April 1946 -

Article

ArticlePlaying Smart

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 -

Article

ArticleA Field of Dreams

May/June 2008 By Lauren Smith '08 -

Article

ArticleAN EASY 1943

January 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR