AMERICA: PURPOSE AND POWER. Edited with an Introduction by Prof. GeneM. Lyons. Chicago, Ill.: QuadrangleBooks, 1965. 384 pp. $2.65 (paperback).

The American scholarly community has had a rich tradition of involvement in the problems of public policy. Academics at the turn of the century were prominent in the progressive movement, the nation's first broad effort to adjust to a complex, industrialized society; distinguished social scientists at the University of Wisconsin helped draft Governor Robert LaFollette's widely imitated legislative program. In 1918 the "Inquiry," a staff of area specialists including Dartmouth's Frank Maloy Anderson, accompanied Woodrow Wilson to the Paris Peace Conference. Franklin Roosevelt's pragmatic use of a "brain trust" drawn largely from the Columbia University faculty is quite familiar, of course. By midcentury the vital role of expert counsel in the making of fiscal and defense policies has been institutionalized in the Council of Economic Advisers and the RAND Corporation.

The volume under review represents a continuing commitment by Dartmouth to this tradition. When the College established the Public Affairs Center in 1961, one conscious purpose was "to encourage and provide opportunities for research and writing in the basic issues of public policy by members of the faculty." The Center's director, Gene Lyons, invited a group of Dartmouth social scientists to participate in monthly discussions about the problems of American society. The writings which the seminar stimulated make up the book.

The nine essays are divided into three units. In the first section three young historians examine aspects of the American past. Roger Brown, who participated in the seminar but now teaches at American University, describes Americans' persistent belief that the United States has a unique mission in world affairs. Harry Scheiber convincingly demonstrates that "the American economy was never isolated nor was American economic growth ever shaped exclusively by internal forces." The editor showed excellent judgment in reprinting the essay by Rowland Berthoff of Washington University, St. Louis, the only author who was not a member of the seminar. Berthoff contends, "the central and continuous factor throughout the history of American society is its characteristic mobility."

In the second unit three Dartmouth social scientists examine aspects of America's role in international affairs. Gene Lyons discusses the strains on American society produced by the Cold War. Meredith Clement deftly analyzes the impact of common markets on our economy. The College's distinguished Latin Americanist, Kalman Silver!, outlines a conceptual approach to the problem of modernization in underdeveloped nations.

The final part deals with domestic issues. Professor Robert Guest of Tuck School and two College political scientists, Frank Smallwood and Vincent Starzinger, discuss automation, urban growth, and civil rights, respectively.

These essays suggest at least four ways in which scholars can enrich the discussion of public affairs. The most common role which contemporary academics seek to play is that of impartial consultants who logically delineate possible solutions to a problem and who project the probable implications of each alternative on the basis of data they have compiled. Thus the electorate and officials can select with greater precision those options which promise to meet their needs and values. Professor Lyons identifies himself with such an approach in a brief but discerning discussion of the relationship of the expert to the democratic process. Professor Silvert argues that modernization not only depends on economic development but also requires modern men who instinctively employ these rational methods. Indeed, the entire volume is designed as the first stage of this kind of broad diagnosis of the problems of American society and analysis of the forces which condition our choices. While the essayists are rationalists, they, like most mid-century intellectuals, are nevertheless aware that reason has its limits and human irrationality is ineradicable.

A second and more limited service which a scholar can perform is to penetrate the mythology clouding most controversial issues. Unlike most public officials who often are prisoners or even perpetrators of such mythology, a scholar, if detached and disinterested, may show how terms have become triggers of emotion rather than tools of reason. Thurman Arnold's The Folkloreof Capitalism is an obvious example.

Professor Starzinger's analysis of the problem of civil rights is superb in this way. He argues that the "equality of opportunity" which civil rights supporters seek is but a new kind of discrimination. Though they would neutralize "birth, wealth, and race," they would substitute ability or intellect as criteria for advancement. However, he similarly attacks the arguments of those who oppose federal intervention to preserve civil rights; for he shows that their appeals for "freedom" from coercion ignore that coercion is an inevitable concomitant of any democratic decision. In moving from conservative premises (a pessimistic view of man, a Hamiltonian idea of national government, an appreciation of tradition) to conclusions that would please most contemporary liberals, his argument is a tourde force of logic laced with irony.

The perception of otherwise unappreciated social problems can be a third function of scholars. Though public officials are popularly believed to be involved in the "real world," much of a modern bureaucrat's work depends on abstractions which say little about life and which often obscure human needs. For example, poverty in midcentury America was discovered not by welfare officials but by a young intellectual, Michael Harrington, who saw the poor as individuals with needs, not just as statistics.

Robert Guest is similarly perceptive. He quotes extensively from an interview with an auto worker who welds "the cowl to the metal underbody. .. . Exactly twenty-five spots. . . . Takes me one minute and fifty two seconds for each job." Well paid and secure, the worker is nevertheless dissatisfied with the "steady push of the conveyor - a gigantic machine which I can't control." He complains that he can "never reach a point where [he] can stand back and say. 'Boy, I done that one good. That's one car that got built right.'" As the worker says, "It's easy for them time-study fellows to come down here with a stop watch . . . but they can't clock how a man feels. .. Through empathy Professor Guest conveys a sense of how "a man feels" when working on an assembly line and thus gives new depth and precision to our understanding of this old but growing problem.

Finally, a social scientist need not address himself directly and self-consciously to public issues; for he can contribute to policy discussions simply by being an able scholar within the normal frame of his discipline. For example, the recent Moynihan Report on the Negro family, which has helped shape policy, drew upon the insights of sociologists and historians whose primary goal had been scholarly investigation.

While Rowland Berthoff's essay is purely historical analysis, it could also be quite useful to those who are concerned with current social disorder. He argues that an initial period of social stability and homogeneity in America which existed until about 1815 was followed by a century of severe civil disorder and class hostility due to "enormous migration, immigration, and social mobility." He concludes that such group conflict has declined in recent decades, however, and a more stable social order has been re-established. The growing civil unrest in the last five years since he first published the essay seems to vitiate his conclusions about contemporary stability. But the groups, white or Negro, most given to disorder now also seem to be those who are most inhibited by race or ability from achieving upward mobility; and the celebrated success and tranquility of most other groups in America only increase their aspirations and accentuate their frustration. Thus the perspective of BerthofT's essay helps us appreciate the anger of displaced minorities who are everywhere confronted with an otherwise rather homogeneous society.

With the exception of Roger Brown's chapter, the essays reveal little of the greyness which this kind of project often pro- duces. The general reader as well as the professional will find them stimulating and authoritative. Yet whatever this volume's important successes and occasional shortcomings, it has a larger significance.

Increasingly and dangerously parts of the scholarly community and American society are becoming mutually alienated. This is partly due to many Americans' intolerance of fresh, ideas and to a disturbing reluctance by some to concede that professors are citizens too. But this alienation is also due in large part to attitudes of many academics. Some scholars regard their compatriots with condescension, even incipient elitism. When they do speak to public issues, too often they do so ex cathedra. Other scholars retreat into the convenient sanctuaries of their professional specialties.

This volume's principal significance to me is that some of Dartmouth's most talented faculty with the College's support are trying to bridge this gulf. They are acting simultaneously as responsible citizens and inquiring scholars by addressing themselves to public issues with the finest tools of their profession. Those who reject the propriety of such a commitment should visit Baker Library and ponder Orozco's chilling indictment of lifeless scholarship in that panel of his mural which depicts the birth of an infant skeleton wearing a mortar board and attended by professional cadavers in academic robes.

Instructor in History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePeace Corps Professor in Bolivia

December 1965 By ROGER C. WOLF '60 -

Feature

FeatureBaker Holds the Key

December 1965 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ -

Feature

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

December 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

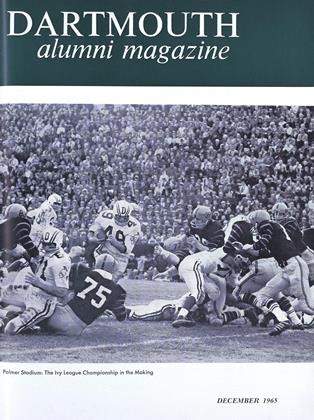

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

December 1965 By R.B. -

Article

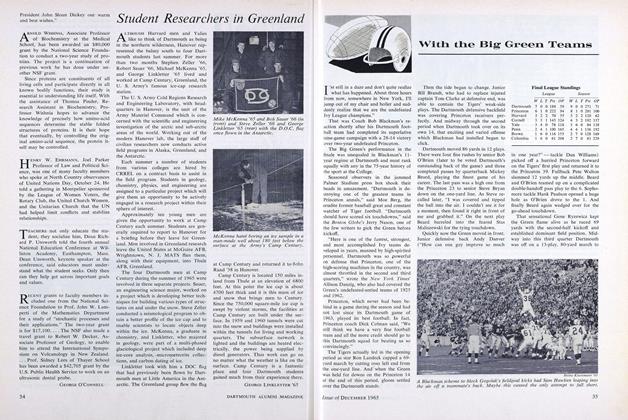

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

December 1965 By JOHN HURD '21

Article

-

Article

ArticleORGANIST AND CHOIR GIVE NOTABLE RECITALS

JUNE, 1927 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

October 1954 -

Article

ArticleQUICK HITS

July/August 2008 -

Article

ArticleBelinda

MARCH 1963 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1941 By Charles Bolte '41. -

Article

ArticleFor the Marines

March 1945 By Pvt. Robert G. Marotz USMCR.