Robert M. Morgan '24, President of the Out: ing Club last year, has been accepted as a member of the Mt. Logan expedition. Mt. Logan, 19,860 feet, the highest in Canada, has never been climbed, and the Alpine Club of Canada is sending a strong party for a try at it. The leader, Mr. A. H. MacCarthy, and Col. W. W. Foster made the first complete ascent of Mt. Robson, highest of the Canadian Rockies proper. Mr. Lambart, in his work on the Alaska-Canada and Alberta-British Columbia boundry surveys, has done an enormous amount of difficult mountaineering. Mr. Carpe last summer explored and climbed a whole group of unknown big peaks in the Caribou Range. The three others have made names for themselves as climbers. That Morgan should have been accepted is therefore something of an honor, both to himself and to the reputation of the D. O. C. He accepted as one of the three "volunteer" members, who are to serve as directed. This may well mean that they will have to do the heaviest part of the final back-packing in order to save the strength of the summit party, and hence have no chance at the top. But one never knows what may happen in a long expedition. Two Alaska packers have also been engaged.

Mt. Logan is in the S. W. corner of Yukon Territory, 20 miles E. of the Alaska boundary, 70 miles north from the sea. The St. Elias Range lies between Logan and the sea, and the expedition has to go in from the north-west. They sail from Seattle about May 1, land at Cordova and take the Copper River and Northwestern R. R. to McCarthy, about 100 miles from the mountain. The first SO miles, up the Chitina River, can be travelled by pack train. The rest is back-packing on glaciers and moraines. The route lies up the Chitina, Walsh, Logan and Ogilvie glaciers to the ice fall of the King glacier—about 30 miles of laborious but not technically difficult marching. From there the route is only slightly known. Mr. MacCarthy went in last summer to make a reconnaissance. He was 44 days from McCarthy, of which all but 10 were used up in getting to the King glacier and back. And the weather was so bad that he had but a fleeting glimpse or two of the higher slopes. He thinks it looked possible, however. The ascent from the probable base camp will involve a climb of over 11,000 feet, and a traverse of nearly 12 miles at from 10,000 to 18,000 feet before the base of the final dome is reached. It is a huge mountain, and a big job. The whole region is drowned in ice. All fuel has to be packed in. The leader left Seattle Feb. 7, to go in with dog teams before the snow melted and get in the bulk of the supplies, establishing depots along the route. It seems probable that one, perhaps two, high bivouacs will have to be made above the King ice-fall. Altogether, the problem has strong similarities to that of Mt. Everest. The great difference is that on the latter real climbing begins at a level 1000 feet higher than the top of Logan, and the exhaustion due to insufficient oxygen has defeated two expeditions. On the other hand, the altitude to be climbed and the distance travelled above the last glacier camp are much greater on Logan, and the man power of the expedition seems inadequate for pushing well-stocked advanced camps beyond the ice-fall. No Himalayan coolies are available, unfortunately. It looks as if the final stage would have to be a grind of exhausting length, easily frustrated by bad weather. Weather and snow avalanches seem to be the chief dangers. However, even the leader knows comparatively little about the task, and the actual circumstances may prove very different.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Oldest Building on the Campus

April 1925 By Professor Herbert D. Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleTHE OLD SONGS

April 1925 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleTo what has been written

April 1925 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

April 1925 By Ralph Sanborn -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1925 By Perley E. Whelden

Article

-

Article

ArticleYEARS MUSICAL PROGRAM ANNOUNCED BY DEPARTMENT

August, 1923 -

Article

ArticleWhat’s New?

OCTOBER 1962 -

Article

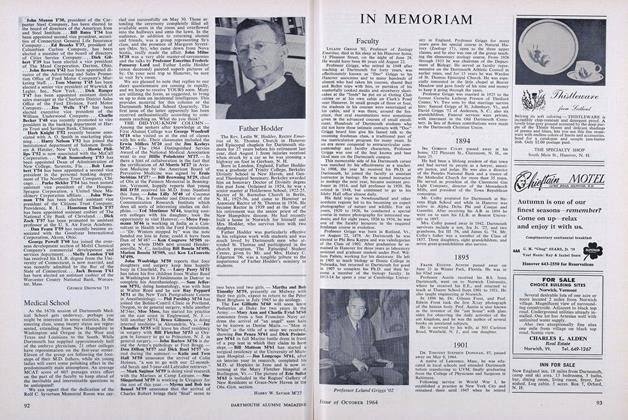

ArticleFather Hodder

OCTOBER 1964 -

Article

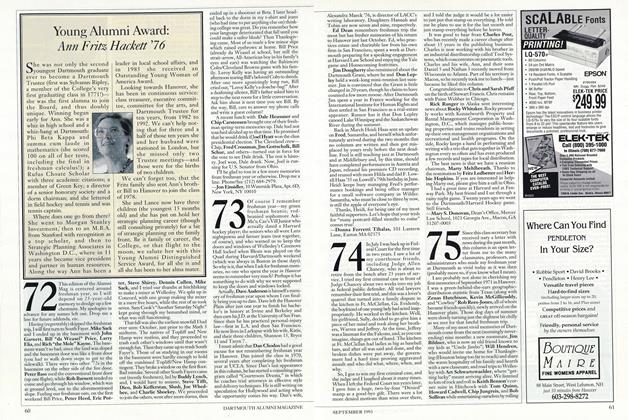

ArticleYoung Alumni Award: Ann Fritz Hackett '76

September 1993 -

Article

ArticleSoccer

By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleA Two-for-One- Convocation and the Med School's 200th

NOVEMBER 1996 By E. Wheelock