The two letters which follow, bearing on the recent publication "A Study of the Liberal College" by Professor L. B. Richardson 1900, have just come into the possession of the editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, by what means he will not say. As they will be of interest to those who have read the book, and may occasion others to read it" who have not already done so, he is risking the displeasure of the writers by printing them herewith. The first letter is from the secretary of 1900, the second from a member of the Class of '99. Editor.

April 10, 1925 Judge Charles H. Donahue, 18 Tremont Street, Boston, Mass.

Dear Charlie: I was just a little surprised to have you ring me up and ask whatf I thought of Professor L. B. Richardson's Study of the Liberal College. It was however, an indication to me that since you have been promoted to the bench, you have raised yourself above your environment. I am of course referring to the very great intellectual handicap necessitated by your constant association with the class of '99.

I am going to tell you what I think about the book in a rather offhand way. In the first place, I was surprised that it was so very interesting. I expected from a college professor a treatise rather than a novel. I thought the style would be precise, lacking in humor and matter of fact. That shows that I did not know my own classmate as well as I should. The book is just full of philosophy, kindly and bright humor and has the action of fiction. It is so persuasive and logical that one is inclined to accept at once all its conclusions. I have to say like everyone else who has read it, "I didn't know that L. B. Richardson was such a versatile man. I ought to have known it because he is one of the outstanding members of our class."

I like the very orderly way in which the book is planned. It starts with the environment of a boy before he comes to college and treats of those conditions in American life which make it difficult for the college to appeal to him in an intellectual way. It makes us wonder whether our boy has the home environment which he should have in order to make his college career a successful one from the standpoint of the real things that count. Are we running the chance that the youngster who we think is so perfect will flunk out at the end of the first semester? If he does get through college will he be just a money maker or will he care for those things in life which make old age delightful? Are we still of the opinion that a college degree gives a boy an education or do we realize that it just gives him a start on that education which is a continuous process through life?

L. B. seems to accept the conclusion that he is going to have a good time and that it isn't a good thing for a boy to do nothing but study. If you throw out athletics, fraternities, rushes, Delta Alpha and all those things, something else will take their place which probably will not be as good. Remembering as I do, the Delta Alpha initiation which your crowd gave me in Wentworth Hall, I have always had a great longing to have some son of a '99 man a Freshman in the same dormitory where my boy was a Sophomore.

I was very much interested in the very clear description of life at Oxford and Cambridge. They certainly do have many advantages which come from long traditions and a society quite different from our own. Thinking in terms of Dartmouth, and that is about all the way that any one of us can think, I much prefer our American liberal college. I should not like to see Dartmouth an Oxford or a Cambridge and I don't think L. B. Richardson for one minute wants us to do so. Oxford and Cambridge seem to me a little self-sufficient which probably they have a right to feel. Tradition rules and the environment is that of past ages while the world today is a rapidly changing world. In our American colleges we are endeavoring to adjust ourselves constantly to the changes which are taking place. Oxford seems to me like a place where one can go and forget the world and live in the traditions of the past. Then too, the contact which Oxford and Cambridge students have with other institutions is very limited. They probably consider the University of London and the provincial universities much as we used to think of Amherst and Brown when we were in college. The Dartmouth winter carnival gives me more of a thrill than the boat race between Oxford and Cambridge. Not having seen the latter, I feel perfectly qualified to make this comparison.

On the subject of sport I suppose it may be safe to express an opinion. Shall there be a marked distinction between sport for the masses and sport for the classes? Professor Richardson admits that there is a higher average of sportsmanship among the masses in America than in England. Has not the American college been a factor in bringing this about? Every year sees greater progress in the idea of "fighting hard but winning fair." Side by side the poor boy and the rich boy do their best and contribute to the idea of true democracy. You must rub shoulders with everyone in life and why not begin early? The sand lot and the college campus have the, same spirit of equality although the code of ethics may be on a higher plane on the latter. Many a talented ball player has developed from catching flies for the sodas on the campus. To some degree at least the spirit of sport must affect the spirit of study.

I am not going to talk much about the curriculum or methods of instruction. I don't know anything about them. I suppose that in our day Clothespin Richardson's course would have been called a snap course, yet I don't think there is any course that we remember so vividly even though we didn't own a text book. I should dislike to see such a course eliminated although I realize that there are very few Professor Richardsons.

The idea of specializing on someone subject I like; it is already being done at other universities and colleges. Just what would have been my specialty at the time I was in college, I don't know. I have always felt that I got the most out of my course at least from the standpoint of future enjoyment, from the wide number of subjects which I learned a little about. I suppose that as a future Judge you would have selected Psychology and Logic; I am wondering if you are not a better Judge because you know a little about Biology, Chemistry and Sociology. Maybe a hearing knowledge of Spanish, Italian and Greek might be of help to you in some cases. Nevertheless you are a Judge basically of right and wrong, and of the true application of the law to the cases which come before you. Anything which contributes toward your general knowledge I think makes you a better and wiser judge.

However, Professor Richardson's book has this very fascinating quality it is so well written and most of the conclusions are so sound that one constantly says, "Well, that's just what I thought."

The specific position which Professor Richardson takes with respect to the graduate schools who furnish the bulk of the material for college instructors, will, I imagine, meet with a great deal of criticism from educators in general. I think, however, that the alumni will largely agree with his conclusions. It was not always the man who knew the most in our day who could impart the most, in fact the reverse was quite generally true.

Professor Bartlett's article in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE occurs to us im- mediately. The one thing that he asks of our college professors is that they shall have an interest in something besides their own subjects. It may be hiking to the Outing Club cabins, collecting mushrooms, growing flowers, but at least it must be something that will draw them away from an intensive life and make them interested in human life in general. They must have broad sympathies and see the relation of their subjects to knowledge in general. If a teacher in our day was a real human being he had a better chance to interest us in his subject. How many courses can we remember which were elected because of the personality of the professor?

I think the only thing to do is get a bunch of fellows together and talk this book over. That is the process that Professor Richardson followed in writing the book and I think that is the process we will have to follow in absorbing it. univer I should like to propose a debate between the classes of '99 and '00, picking out a profound subject like, "Is one snap course per year essential to the curriculum of a liberal college?" Following the sportsmanship which has always prevailed in our class, we will allow you to take either side of the question. We will also eliminate the author of this particular book which is another way of saying that no expert testimony will be admitted.

In closing, I want to say that a rather peculiar reaction occurred in my family. It was proposed that we send our boys to the University of Edinburgh. My own conclusion, which I think is more practical, is to send them to the Massachusetts Agricultural College at Amherst. There may be no alternative if the intellectual progress of the College continues at as rapid a rate as it has during the past ten years.

Very truly yours,

NATT W. EMERSON

April 13, 1925 Mr. Natt W. Emerson, 30 State Street, Boston, Mass.

Dear Natt:— When I rang you up the other day it was not with the intention of entering into an exchange of letters with you on the subject of Prof. L. B. Richardson's "Study of the Liberal College." I merely wanted to say to you politely but firmly that L. B.'s book is such a fine piece of work both as to matter and method that I hoped that even you, High Priest of Class Consciousness that you are, must realize that his conspicuous success has come not because of his class affiliation but, rather, in spite of it.

Your letter impels me to reply and not because you think so highly of L. B.'s work, an opinion which I fully share. I agree that Prof. Richardson has returned from his argosy with rich treasures gathered from the universities of the old world and from the sities and colleges of the new and that more value has been added by the setting, wrought from his own experience and thought, which he has provided for his collection. Here, for sure, is a book that every alumnus should read, must read, in factf if he is to follow with intelligence the educational policies of the College: for this is a book which inevitably must have an effect on the future educational life of Dartmouth.

Although in your letter you disclaim any intention of talking "much about the curriculum or methods of instruction" you seem, nevertheless, to assume that Prof. Richardson's conclusions as to educational processes provide proper subjects for alumni discussion and constructive criticism. Much as my class would welcome a contest of any sort with yours, even a debate if unfortunately nothing more strenuous can be arranged, we must insist that the subject be a legitimate subject which your champions are qualified to discuss. I really feel that the ordinary layman alumnus is not qualified -to review that part of L. B.'s book which suggests changes in curriculum or methods of instruction.

While the alumni of the College are rightly concerned with the aim of the College in its educational policies, only the expert, it seems to me, can pass upon the educational processes employed. In your letter you have endorsed in toto the conclusions of Prof. Richardson which are, of course, conclusions as to educational methods. Any institution which produces, whether it be a college or a hat shop or an automobile factory, must be willing to be judged by the world on its product. It is, however, it seems to me for the producing institution and not for the consumer to choose and to regulate the machinery which produces the result, whether the product be college graduates, or hats, or motor cars. You and I, and the world, choose or reject he finished hat or automobile according as it suits or does not suit our needs. We can demand that the producer furnish us with a certain style of hat or type of automobile, may properly criticise the result of the manufacturing process and even stop buying any more if his hat does not wear or his automobile run well. But we really are not qualified to dictate to him the methods used in production. So, it seems to me, the real concern of the alumni as a whole in a book so destined as Prof. Richardson's to be influential in shaping the type of Dartmouth men of the future, is confined to the aims therein stated and the results guaranteed from such changes in educational methods as may be suggested.

While methods are of supreme concern to the producers* of Dartmouth men, we as consumers can rightly look only at the result of production. As custodians of the extra curricula spirit and tradition of the College, we may well claim a voice in the definition of the type of Dartmouth man to be produced and properly criticise variations in type caused by the formative processes but, it seems to me, the processes themselves are technical matters which must be left to those trained experts whose calling in life it is and whose responsibility it is to adopt at their peril the methods adopted to produce a desired result.

Those charged with the business of education at a college might in the selection of applicants and in the prescribed training entirely change within a college generation of four years the type of graduate. They might for instance decide to admit only men lame in the left leg whose grandfathers were college graduates. On the other hand they might accept only red-headed men whose grandfathers could not read. They might either prescribe as the only study "Evolution," or else furnish as the only courses instruction in advanced plumbing and super-carpentry. Perhaps on some of these slightly radical suggestions (which are not made by L. B.) as to changes in curriculum and personnel, you and your classmates might be competent to form, and to some extent express, opinions of worth as to the type of Dartmouth men likely to be produced if these suggestions were adopted. But what can we helpfully say about the effect of "abandonment of separate arts and science degrees," "fewer courses in the last two years with more concentrated work in each," "some form of the honors course," "reappraisement of the relative value of teaching ability and skill in research" or the "elimination except in Freshman year of prescribed courses or those with narrow options" ? Isn't it for the expert to say which of these processes should be employed to produce the desired result and shouldn't we confine ourselves to debating on what the result to be desired is?

To illustrate:—I concede that you are a very desirable type of Dartmouth citizen but I am wholly unprepared to say whether or not that result is due to the courses in Fine Arts, Wyckliffe Bible, Geology and Botany and similar studies to which you devoted yourself so assiduously while in college. Nor do I see how you can very well take either the affirmative or the; negative on a proposition to eliminate courses of the kind that you yourself took. Sincerity will require you to oppose bitterly any changes in a curriculum which produced such an admittedly satisfactory result and surely modesty will deter you from claiming that you are what you are in spite of your collegiate education.

Let the debate then be upon the subject of the type of Dartmouth graduate which, as the alumni see it, is needed by the world in which the graduate is to live his life rather than on the educational formulae which will best produce such a type.

Yours sincerely,

CHARLES DONAHUE

Paddling Upstream

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

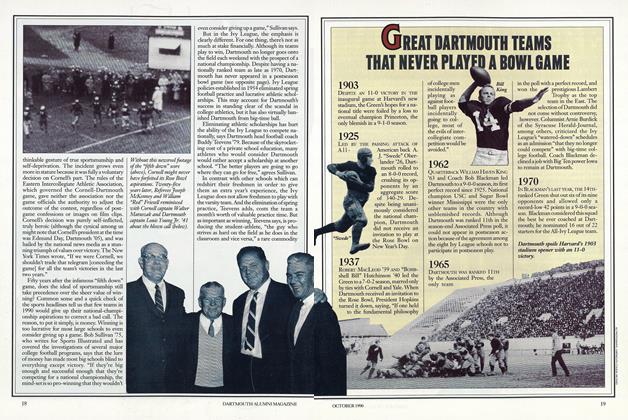

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICAL FITNESS*

May 1925 By WM. R. P. EMERSON, M. D. -

Article

ArticleWHEN THE KING OF FRANCE CAME TO DARTMOUTH

May 1925 By Eric P. Kelly 1906 -

Article

ArticleLife, as the newsboy remarked

May 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

May 1925 By Ralph Sanborn -

Article

ArticleThe Attitude Unworthy

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleTHE LEDYARD CRUISE

May 1925 By Evan A. Woodward '22