I

Charles Louis, known to history as the Lost Dauphin, was born March 25, 1785. When his father King Louis XVI was led away to imprisonment and execution during the French Revolution, the young prince was handed over to a cobbler by the name of Simon who treated his young charge with such hideous cruelty that the boy was reduced to a condition of idiocy. After the fall of Robespierre and the execution of Simon, the boy was given better treatment. The Convention in December, 1794, decided however that he should be sent out of the country. In June, 1795, it was reported to the Convention that the youngprince was dead.

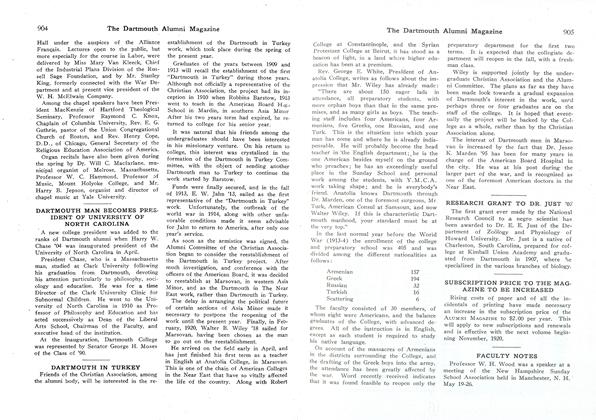

The circumstances surrounding the case are too well known generally to need repetition,—the failure of friends to recognize the dead boy as the Dauphin, the anxiety of the French Government to be rid of the embarrassment of a living Bourbon, the mystery surrounding the whole process of preparation for burial, and burial itself, of the boy said to be Louis XVII. In 1818 the French Minister Genet stated in New York that the Dauphin was not dead, but was still living in New York State. In 1832 at the time of the accession of Louis Philippe, a certain Le Roy de Chaumont returned to France carrying a report of a boy left among Indians at St. Regis or Caghnawaga. In 1838 a man living under the name Belanger died in New Orleans, and made a death-bed confession to the effect that he had brought the Dauphin from France to America via the Low Countries and England. In 1841, the Prince de Joinville came from France seeking, as has been proved, a certain Episcopal clergyman bearing the name Eleazar Williams, supposedly an Indian, a missionary among the Indians at Green Bay, N. Y. Eleazar Williams reported that the Prince told him definitely that he, Eleazar, was the missing Bourbon, and therefore the legal King of France.

Eleazar's Case was then taken up by several persons, among them two clergymen, the Rev. Francis L. Hawkes of Calvary Church, New York, and the Rev. John H. Hanson who published his findings in Putnam's Magazine in 1853. It was proven conclusively:

1. That Eleazar, dr Lazau as he was known among the Indians, was not a member of the Indian family in which he was first found.

2. That he was placed in the Indian family, that of Thomas Williams, in November, 1795, when the family was near Albany.

3. That no baptismal record with his name on it was found, although the names of all the other Williams children were registered.

4. That boxes containing clothing and medals of Louis XVI were left with the Williams family by the man who brought the boy, one of these medals being found and kept by Mr. Hanson.

5. That the boy's body bore the same scrofula marks as that of the Dauphin, and that he parried two wounds on his face similar to those inflicted on the Dauphin by Simon who beat him with a towel in which there was a nail.

6. That the boy's guardians were constantly receiving money from unknown sources.

When Eleazar was about 10, or 12 years of age, he struck his head against a stone while diving in Lake George. Previous to that time he had all the earmarks of idiocy. On recovering consciousness he seemed to be suffering from a "double personality," and was, to all intents and purposes, another person. He was possessed of a fine sanity, however, as his after-career showed, and the investigators came to the Conclusion that the accident and blood letting had somehow restored the sanity which had departed, as they said, under the cruel treatment of the jailor Simon. He lived through a curious boyhood in this family, seeing from time to time mysterious French strangers who looked at him and made strange remarks.

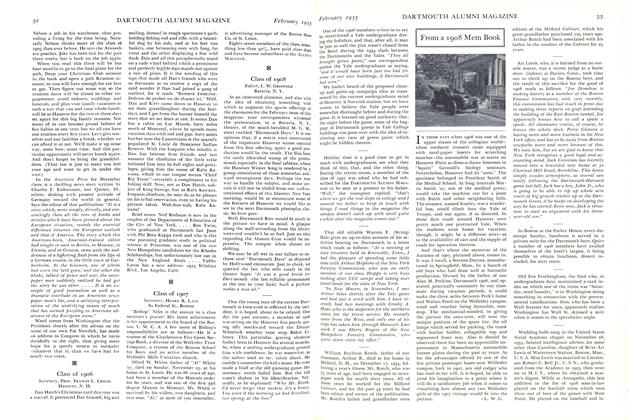

The accompanying illustration shows that he did not possess Indian features. His skin was white, and in later life he bore a marked resemblance to Louis XVIII. His features were said by those who observed him to be distinctly Bourbon. He had a quick aptitude for study after he had been adopted by Nathaniel Ely of Long Meadow who had in mind sending him to Moor's Charity School at Hanover, and later of sending him to the College. He received most of his education privately as he found it hard to remain away from home. An old illness constantly bothered him, the direct result of some ill treatment that he had received in earlier years. In 1807 he came to Hanover. Some of the incidents of that stay at the College I am recounting later.

Finishing his education in 1812 he enlisted in the American Army and did meritorious scout service throughout the war. He was wounded while leading a charge at the battle of Plattsburg. Giving his attention thereafter to the ministry, he went as a lay reader among the Oneida Indians in 1816. When they migrated to Green Bay in 1822 he went with them. In 1823 he married Miss Jourdan, a relative of Marechal Jourdan of Napoleon's Army. He was ordained a minister in 1826 and spent the rest of his active life working among the people with whom he had cast his lot. It was said of him that his extreme politeness and gentleness were noteworthy, that he possessed a natural grace and dignity that won him friends everywhere. Just how much he suspected of his birth and parentage up to 1851 is not definitely known, although Mrs. Mary H. Catherwood in her novel Lazarre, published in 1901, concludes that he knew of his royal descent since youth.

II

One of the few men in the history of the United States who might have been successful claimants to a foreign throne was this Eleazar Williams, a supposed Indian boy, who received from Dartmouth College money for a mission among the Indians,—who was a candidate for admission to Moor's Charity School as early as 1802; who finally made a trip overland from Long Meadow, near Springfield, in 1807 supposedly to continue his studies in the College. He was a handsome boy at that time, about nineteen to twenty-two years of age, with refined features, and white skin, although he was thought to be an Indian boy from Caghnawaga, near Montreal, a descendant of Eunice Williams, the celebrated prisoner who married among the Indians and ever refused to return to- the ways of civilized peoples.

The story of the Williams family of Deerfield is too well known to be repeated here. It only concerns the history of Dartmouth College that in 1772, Eleazar Wheelock, the College's founder, was much interested in the report that several of his missionaries among the Indians had gotten hold of Eunice's grandson (an uncle of the supposed Bourbon) and had persuaded him to come to Dartmouth. Eunice was then a very old woman; she had outlived all the other members of the Williams family who were involved in the sacking of Deerfield and the ensuing captivity, and she, it was reported to Wheelock, went to the prospective student of the College and threw her arms about his neck and succeeded in persuading him not to forsake the Indian culture for that of the whites. He was taken severely ill at that time, which also worked against the efforts of the missionaries, and he did not come to the College or the Moor School, although several of his companions did.

But New England held the Williams family as something famous in those days, and many hundreds, perhaps thou- sands, of pounds were spent in the ef- fort to reclaim not only Eunice, but her descendants from "savagery.". Eunice's daughter Mary, married an English phys- ician, named Williams. Mary's son, Thomas Williams, married an Indian woman named Konwatewenteta. It was from this family that Eleazar Williams, known among the Indians as Lazau, was taken in 1800 to live with Deacon Nathaniel Ely of Longmeadow. The boy was then apparently about twelve to fif- teen years old. The following letter, writ- ten two years later by Ely to the board which had supervision over Indian Char- ity money, is in the Dartmouth Collection of letters, and has been kindly furnished by Mr. Harold G. Rugg of the Dartmouth Library:

"May 29, 1802.

"The Indian Boys Viz Lazau Williams in his 14th year and John Surwattis Williams in his 10th year—The two lads were brought to Longmeadow, Jan. 23, 1800—they have lived with Deacon Nathanl Ely under whose immediate care they have been, and on whome they have depended for their support—he prays the Honourable Board of Correspondents in Boston—Should it be their pleasure to take the case of the lads under consideration, and should they in their wisdom see fit to give some assistance for their support—although to a small amount it will be very thankfully and gratefully received.

"N.B. They came in their Indian dress, out of which they were soon taken and put into the English—they could not speak English-—the Eldest could speak sum Canadian French. They are of the Cahnawaga tribe which is a part of the Six nations—The prime object of those who have the care of them is a Christian Education and that they may (be trained?) for schoolmasters or missionarys—to their countrymen Should they under the Smiles of Providence be furnished for that purpose.

They have learnt to read and write sum, but are not perfect in either—their natural abilitys are good, and as yet they appear to be well disposed, orderly lads. -—they are descendants of the Rev. Mr. John Williams of Deerfield who was carried captive to Canada—their great grandmother was Eunice Williams, daughter of the above Mr. Williams, who was captivated at the same time and married in Canada to one Tunnogen an Indian."

The petition for help for the boy and his brother did not result in schooling at Hanover, however, but in 1807 when Eleazar was about 18 or 19, he came to Ha.nover on his travels. John Wheelock was evidently interested in him, as Eleazar's diary indicates, and so was Professor Smith; whether he had a college education in mind, or whether he was just concerned in appealing for help in proposed Indian work is something of a question. Mrs. Catherwood believed that he spent a whole year in Hanover, but the old books of the Moor Charity School do not seem to furnish such proof. The young "Prince" is entered on the Moor Books in two places, as nearly as I can at present ascertain, although I hope that more material will be available about this historic person.

On one of the old Moor books, under the date of Nov. 11, 1807, I have found that six pounds, five shillings, and three pence were bestowed upon Eleazar to allow him to go upon a mission to Springfield, a distance of 130 miles, as the book says. Just how long the young "Prince" had been at Dartmouth, or rather at Hanover, I have not yet ascertained, but there is another entry in an account book of the Moor Charity School of January, 1808, in which the cashier or treasurer makes an explanation of the case which seems to be the satisfactory one.

It is to this effect: "Paid to Samn Dewey, for one week's board of Eleazar Williams, a "Cagnawaga" Indian youth preparing to enter the school, but being unwell went to Connecticut—total Twelve pounds, seven shillings, eleven pence. Board 8 shillings." Thus one might believe that the supposed Bourbon was taken with illness, an illness to which he seemed to be subject, which he mentions in his diary, probably the result of harsh treatment in his earlier years. If only the Mary Hitchcock Hospital and the selective system had been in operation at that time, the College might have restored to health, and admitted, a real aristocrat, of both brains and blood, for Eleazar was uncommonly cultured, and uncommonly intellectual.

See what he says in his diary about Dartmouth: "Hanover is a fine place. The College and other buildings are elegant. The village contains many handsome houses, surrounding a spaciouplain which in summer is always covered with verdure. The whole appearance is charming and the inhabitants are noted for their hospitality and polite attention to strangers. I was introduced to Rev. Dr. Smith, Professor of the Learned languages. I was agreeably entertained with several of the students. I have experienced that there are many temptations to which a young man is exposed, but if he is inclined to sustain a good character, he must associate only with those who are virtuous. The younggentlemen appear to be scholars, but Iperceive that there is something wantingin them to make them complete gentlemen. Modesty is the ornament of a person."

It might be added that when this extract from Eleazar's diary was printed in the Putnam articles, some Dartmouth wag wrote across the page in large letters, "Bravo Dauphin."

There is room for a future Dartmouth drama in this sketch: imagine if you can the two Indians then in Dartmouth, Old Louis Annance and Paul Gill, gathered with Williams perhaps in the college building, old Dartmouth Hall, perhaps under the very bell tower in the room where students rang the bell -for so many years. And amidst the protesting of that day against Commons food, for so it is chronicled in the history in that very time, there came this element of strangeness,—the Indians recognized that here was not one of their own number,—perhaps some French word spoken by these Indians brought back the recollections that had been just out of his beck and call since earliest youth,—perhaps all these factors entered into the story, that there in old Dartmouth Hall a King was made, and unmade too, for Napoleon was ruling in France and the Bourbons were to have but one more silly fling, and then were to pass from the stage forever. At any rate, Eleazar was overcome by something, perhaps the Dewey food, perhaps Commons "grub,"—perhaps by something else that shook him to the very depths of his reason,—I do not know, but I do like to think, that here in Hanover, at this place where the Indians used to find a haven from their wars, and rest from long trails,—that here in the golden autumn of that distant year, a certain young man wrung from his own tortured brain the secret that he was'a King. And having learned it, he gave up his life to service to a dying race, forgot the glory that might have been his, served his new nation with loyalty in the war of 1812 and received the honors of priesthood in the Episcopal church of America. What he had lost might have been a bitter regret, had he not lived a life of glorious usefulness.

Eleazar Williams [Facsimile of Pencil Sketch by Fagnani, from Original Portrait byJ. of Hartford, 1806]

PROFESSOR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICAL FITNESS*

May 1925 By WM. R. P. EMERSON, M. D. -

Article

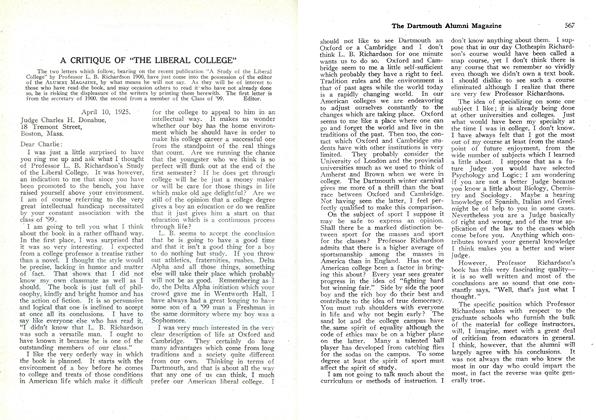

ArticleA CRITIQUE OF "THE LIBERAL COLLEGE"

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleLife, as the newsboy remarked

May 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

May 1925 By Ralph Sanborn -

Article

ArticleThe Attitude Unworthy

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleTHE LEDYARD CRUISE

May 1925 By Evan A. Woodward '22