is just one darned thing after another. Once you get one problem fairly well disposed of another bobs up. It is peculiarly true at Dartmouth at present. The College has worked up its system of subscriptions through the alumni fund to a point where the annual income can be fairly well relied upon to meet the expenses, heavy as they necessarily must be. What gives it the most bother now is likely to be the fact that its lay-out of expenses—all the traffic seems currently able to bear—does not admit of its keeping its stronger professors once it develops them. They get flattering offers from outside and cannot, in justice to themselves, afford to neglect them. As a result Dartmouth loses, every year or two, men whom it would be glad to retain but cannot afford to pay in competition with other and richer institutions.

This situation is probably one which cannot be rectified at once, but hopefully is one which in a decade or thereabouts will become less bothersome. There are in prospect considerable additions to the permanent endowment which will in the process of years come into possession through the demise of interested testators —but of course no one is anxious to have such gifts expedited. It is agreeable to feel that some day benefactions will fall into the lap, but more agreeable still to feel that such generous persons as have promised them still have the prospect of years of helpful living. In the meantime the permanent endowment grows but slowly; and while it enables the meeting of annual deficits and a certain amount of expansion, it does not, and for the time being cannot, put us in position to hold our best men against the blandishments of better endowed institutions.

Teaching is a> business and no one blames the men who engage in it for accepting opportunities for bettering their condition. There is only one way to meet such a condition successfully and that is by putting ourselves in position to pay as good salaries to the best teachers as others can pay. Just now we figure as a very excellent training ground for promising men who are starting on their career as educators, paying them adequately during their earlier years and maintaining the gait fairly well for average talent for some years beyond that. But we are not able, as yet, to meet the competition of other bidders for the exceptional men whose attainments have arrested a wide measure of attention in the educational world. Our maximum salary for a professor is necessarily lower than the maximum in richer collegesin some cases offers have been made which doubled what the man could look for in Hanover.

This does not by any means imply that instruction suffers at Dartmouth. It merely means that men of established reputation and long experience are under a temptation to drift away, instead of being capable of retention after they have reached the maximum of efficiency and standing. The answer to this problem is beyond question the familiar one—money. It reminds us only that we cannot rest on our oars, content with the present and indifferent to the future because for the time being we manage by strenuous endeavor to come out even at the end of each year. There remains much to and we are heartily glad of it. Perfection is finality—and finality is death. Dartmouth has to look ahead to the job of keeping her best educational talent after she has trained it, by paying it what the market holds it to be worth. Otherwise she will lose it, and must forever start fresh in the development of new teachers to fill the veteran gaps.

And of course there's the library. That really cannot be put off more than a year or two. We are ridiculously underprovided in this regard, and the contrast between Wilson Hall and the Gymnasium is not altogether to our credit. There is a vague feeling that something will some day solve this problem—presumably the appreciation of some interested person of large means, who will perceive the unusual chance which this situation offers to serve humanity and incidentally erect for himself a monument more enduring than bronze. This is a matter which it is felt cannot be referred to with too great frequency. It isn't a thing that needs any argument, but it does require an occasional reference to the end that it be kept constantly in the background of our alumni minds. A college without an adequate library is open to most serious criticism—and the solemn fact is that Dartmouth is at this moment in, such a position.

One thing said by the President in his recent addresses to the alumni associations here and there has probably arrested especial attention. That is his striking summary of the growth to which higher education has attained, pointing out that since the establishment of colleges in the United States there have graduated in round numbers 900,000 men—and that at the present moment there are actually in the colleges of the country about 700,000. In other words, there are almost as many students now in the colleges of the land as have been graduated from all the colleges during two centuries and a half.

It is this amazing statement that suffices to show the outstanding difference between education in America and the higher education in England. No wonder we have a problem. Here are all sorts of young men and women—for the problem knows no limitation of sex—some eager for knowledge, and some accepting knowledge grudgingly as an unwelcome condition precedent to being allowed to remain in an agreeable place with agreeable associates. There is so much advantage in making the best use possible of the less promising materialour country's needs being what they are —that we cannot dismiss with indifference or contempt the army of students whose zeal is small, in order to put all our time on the development of those whose zeal and capacities are great. The question raised is that of a more just apportionment. We are said to be neglecting the better students in our solicitude for the poorer ones; and we are urged to correct this, as far as may be, without incidentally neglecting the less eager who must still be nursed along as best they may be to a passing mark.

It is a frequent criticism that no one would suspect the average college graduate in America of having been through a college by anything he says, or does, or reads. This may be a dangerous generalization, but it comes very close to stating a deplorable truth. One has but to run through the lists of his acquaintance to discover that. The reason is beyond doubt that cited with such insisttance by Professor Richardson. The Oxonian is an obvious university graduate. The average graduate of an American college is not obviously a college graduate. It is, apparently, because the Oxford product is concentrated, where the American product is diluted. The British university puts a very high polish on a chosen few; the American puts a very little polish on a great many—or tries to, though sometimes with but transitory effect. Not too many of us betray the educated man even by so much as our use of speech—let alone by the nicety of our appreciations for the things that are more excellent. Ours is a careless age and one sometimes fears that American education hides a diminished ray under a convenient bushel, through dread of being deemed a pedant. In any case American college graduates ought to show more evidence than usually they do of the fact that for four years the professors labored over them—with agony and bloody sweat, so to say—in order to make them eligible to receive a sheepskin. How much does the sheepskin mean? Does it imply permanent attainment as a scholar? Undoubtedly—with a very few. With the rest it is little more than a recognition of the fact that, by steady spurring, a reluctant man has managed to satisfy his instructors, so that they have hastily handed him his credentials with a sigh of relief at the chance.

An inept person may be pardoned for hesitancy in adding a suggestion where the experts seem to be so bothered—but is it not a fundamental truth that the first essential is a genuine interest on the part of the learner to learn? By interest to learn we do not mean the vague desire to be known as an alumnus, or to do just work enough notto be separated from college, but a spontaneous eagerness to know for the knowing's sake. The rare teacher is the one who can inspire that eagerness—and once it is inspired, the rest comes easily.

What makes this whole problem is the utter indifference of the many, who are not exactly averse from knowing, but who lack a hunger and thirst after knowledge comparable to the desire which would make the young man on the billboards "walk a mile for a Camel." Those are the ones over whom the faculty has to labor and drudge, discouraged by the unresponsive coldness and forced to be satisfied with the lukewarmth that may be engendered by persistent rubbingpraying only that it endure long enough to satisfy the official thermometer, and only thereafter lapse again.

If the colleges dealt only with the eager to learn, there would be fewer colleges and much less imposing bodies of alumni thereof. But there you are. Do we really want things different? Of that we entertain a lusty doubt—if having them different would mean a lessened flood of our very imperfectly educated men. The comfortable thought is that God's in his heaven and all's right with the world, so long as we do our part here below and see so clearly what we fell short of doing. We aren't turning out a very scholarly array to represent our colleges. It is possible we may improve somewhat the breed. But we shall never improve it to the Oxford standard so long as our material is so vast and so various—unless we wholly mistake the cicumstances and wholly misread the signs and the portents. We shall improve it somewhat, no doubt—and that, in the last analysis, is what the investigators are trying to tell us how to do.

One of the romantic and inspiring features of an alumni body is the position accorded , to the oldest living graduate. Since he left the college portals he has watched from sixty to seventy classes enter and leave its halls. The college he knew has passed into history and if he has a bent toward philosophizing the material for the purpose is abundant. Alumni of the period around the turn of the last century and in subsequent years will remember the genial and inspiring presence of Judge Cross '41, familiar to many Dartmouth Night audiences. The thrill that came from his reminiscences of earlier days and graduates and his statement that he might have known or seen graduates from every class of the College are still recalled.

The mantle of Judge Cross fell upon Dr. Barstow '46 whose personality was frequently reflected on the pages of this MAGAZINE although he was seldom able to return to Hanover in later years. The succession has passed on all too rapidly to Leander M. Nute '54 and now to Samuel H. Jackman '60. From the East, too, the distinction has been transferred to the far West as Mr. Jackman is a resident of Sacramento.

Some may prefer to define the oldest living alumnus as the graduate of the earliest class having a living representative rather than the graduate oldest in point of years. If this interpretation is accepted we must again go back to the Fifties and recognize two graduates of the class of 1857, Francis H. Goodall of Washington and John H. Waterman of California. The MAGAZINE takes pleasure in presenting this triumvirate to its readers. May they long hold their present position as the representatives of earlier days of the College.

The wisdom of the change from summer to winter as the time of the Alumni Lectures on the Moore Foundation seems to be justified in the results. Both Mr. Tsurumi and Professor Shotwell addressed audiences far larger than those which had gathered or could gather in recent summers on similar occasions. When such vitally interesting and timely material can be made available to the hundreds of students who have taken advantage of the opportunity there can be little doubt as to the desirability of the new arrangement. Nor has the alumni element been lacking during the recent series and it may well be increased in future years as the graduates become more familiar with the opportunity, combined as it is with the joys of a winter visit to Hanover.

Another fixture on the Dartmouth calendar, the annual meeting of the Secretaries Association, has likewise been drifting steadily to a later position in the calendar. This gathering will doubtless be in session as this issue of the MAGAZINE goes to its readers. Instead of the slush and sleet of March, or the mud of April, the secretaries now meet amid all the beauty of an early May in Hanover. Secretaries or official representatives from almost all of the sixty odd classes will be present, besides a score of association officials. Those attending the meetings, frequently express themselves as receiving more of the atmosphere and spirit of the College than on any other occasion. If this is true it is just as much the case that the administrative officers and permanent officials in Hanover receive inspiration and encouragement from the enthusiasm and co-operation of the secretaries. The discussions and deliberations this year promise to be exceptionally valuable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICAL FITNESS*

May 1925 By WM. R. P. EMERSON, M. D. -

Article

ArticleA CRITIQUE OF "THE LIBERAL COLLEGE"

May 1925 -

Article

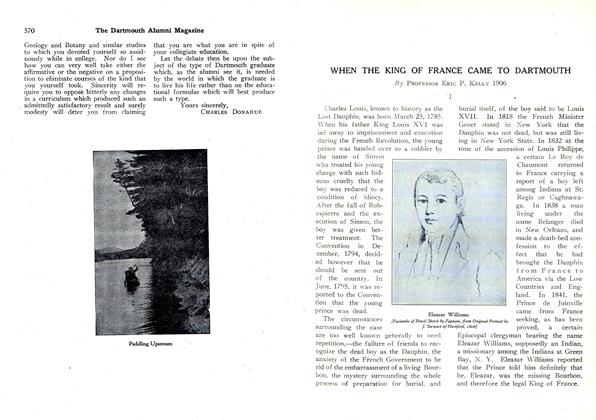

ArticleWHEN THE KING OF FRANCE CAME TO DARTMOUTH

May 1925 By Eric P. Kelly 1906 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

May 1925 By Ralph Sanborn -

Article

ArticleThe Attitude Unworthy

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleTHE LEDYARD CRUISE

May 1925 By Evan A. Woodward '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleDEAN LAYCOCK VISITS ALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

February 1920 -

Article

ArticleHENRY ROOD PRESENTS VALUABLE AUTOGRAPH LETTERS

February 1921 -

Article

ArticlePresent Shock

June 1975 -

Article

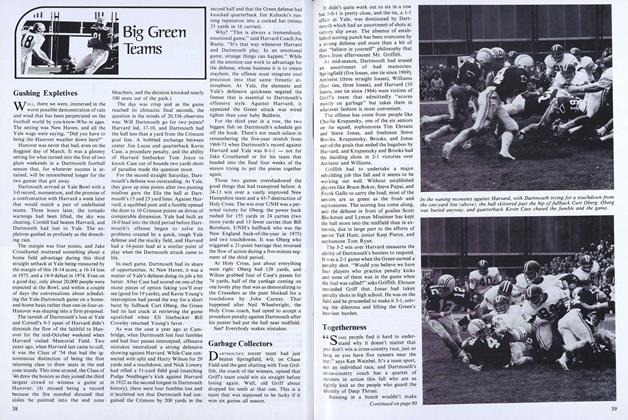

ArticleGushing Expletives

November 1976 -

Article

ArticleSports Schedule

May 1956 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleDan'l Adams, 1797

March 1950 By DAVID E. ADAMS '13