This is the second of several brief articles written by the secretary of the class of 1863 about Dartmouth in the sicties. In the issue of February 1926 an article by Mr. Scales appeared entitled "Dartmouth Two Years Preceding the Civil War." Editor.

It seems proper to me in writing of the Dartmouth of sixty-five years ago that I should mention those who gave my class instruction and training during four years. Hence the following brief mention of them.

Nathan Lord, who closed his connection with Dartmouth College in 1863 having served as president thirty-five years, took no part in our recitations. He usually officiated at the morning chapel exercises, reading a selection from the Bible and offering a short prayer. In the performance of his other duties he seemed to be promptly on hand when any disturbance occurred, and wielded the birch of discipline when it became necessary no longer to "spare the rod" that was needed to conserve discipline and properly train the minds of the young men under his care.

Nathan Lord was the only one of the faculty of whom we had heard before we became students there. His fame as president ranked him among the highest in the colleges and universities of America. To us his fame did not diminish with the signing "N. Lord" on our diplomas at Commencement in 1863. There was nothing small about his view of questions, grant his premises, and there was no getting away from his conclusions. The mistake of his life was in starting from false premises, especially regards negroes and slavery in the southern states. He never mentioned that subject in college. All that we heard came from outside of Hanover. So far as I ever heard, President Lord never expressed views opposed to suppression of the rebellion. His prayer at the departure of the Dartmouth Cavalry, which was stenographically reported and published, shows where he stood as regards the war question. One singular thing about the negro question was that he admitted them to college and one of that race was a member during my time, being one of my class. He remained two years but in his junior year left to become principal of a high school for colored students in Xenia, Ohio, later becoming professor of mathematics in Alcorn University. He was a teacher for more than forty years and has a fine record.

Personally, I was careful to so conduct myself as not to be called officially to hold an interview in the president's office, but I always found him cordial and courteous whenever we did meet. Many amusing stories were current while I was in college of the ways he adopted and used for catching wicked or mischievous students who indulged in tricks and hilarious conduct to the detriment of their studies and the peace and quietness of the college in general. It was useless for the offender to "prevaricate" in answeras ing questions when undergoing an investigation in a faculty meeting. The class of 1863 always esteemed it a great honor to have the autograph "N. Lord" on their diplomas.

John Newton Putnam was our instructor in Greek. His character was perfect ; his face of rare beauty shone with kindred, helpful thought for every one; his wonderful perfection of scholarship, his ready and apt illustrations of points of history, biography, antiquity, and literature were delightful. I now can see him as he sat at his desk at recitations and asked questions and see the look he glanced back at stumbling answers. He had wavy black hair, large dark eyes and his face was a picture to look at and admire. What he said was never perfunctory, never dull. Out of the class room he Was brimming over with fun, puns and exquisitely drawn humor. No one can compute the good he accomplished.

James Willis Patterson was, all in all, our most popular instructor in college. He was in the prime of life, tall, well proportioned, florid of complexion, his face not handsome but giving a favorable impression as soon as he began to speak. He had a strong and pleasing voice and used it in such manner that he made trivial and commonplace topics interesting. He was a careful instructor, versatile thought, courteous in manner and otje of the best orators Dartmouth has ever graduated. He was our instructor in mathematics, astronomy and meteorology but what the boys enjoyed most of all-was some occasion to call him out to make a speech in war time. When exciting news came in from the battlefields, or from the doings in Congress, and excitement ran high, the students would call out "Patt." Then his manner, as well as his language, in delivery, was as eloquent as I ever heard from any speaker. He was a good teacher and a grand man as we saw him in College.

C harles Augustus Aiken was our first instructor m Latin, coming to Dartmouth the same term my class entered college. He wore glasses and when he had adjusted them to "take in" the class order always prevailed, and strict attention was'' given to the lesson in hand. His knowledge of Latin was perfect and he had a .way of quickly finding out what the student in hand knew and especially what he did not know, then gave him the needed instruction. He was quick to see the funny side of any question and enjoyed laughing at the denouement, so always kept the class in good humor. In his questions he always aimed to have the student get at the "root" meaning of the words that bothered him in any passage. I am sure that Professor Aiken, more than any other instructor in college, helped me understand and select the proper words that would exjpress the thought I had in mind in the most intelligent manner.

John Riley Varney became Professor of Mathematics in our sophomore year when Patterson was made Professor of Astronomy. Mr. Varney was a tall, nervous fidgety man with a brain so keen for mathematics that he could see at a glance what would require an hour or two of close study for an average student to cipher out. Being nervous, his patience soon gave out in the recitations of dull students. The students became amused at his fidgety manners and were led to do things to annoy him and make him more nervous. For that reason he was not a success as an instructor, though he was complete master of all branches of the higher mathematics.

Oliver Payson Hubbard, our instructor in Mineralogy and Geology, was up to date in those branches of studies. His manner of instruction was very pleasing and he aroused enthusiasm in the students. I have many minerals now in my cabinet that I collected when under his instruction. He was equally interesting in the study of Genealogy.

John Smith Woodman gave instruction in surveying and kindred topics and was popular with the class. The field work under his direction was much enjoyed, although he was insistent that everything must be done in the most exact and perfectly accurate manner.

Daniel James Noyes was our instructor in Moral Philosophy. He was an easy speaker and had pleasing ways of conducting class recitations, allowing a wide discussion. He was not given to displaying doctrinal theology.

Samuel. Gilman Brown held the chair of oratory and belles lettres and was always popular with the class.

Henry Fairbanks, our instructor in Natural Philosophy, was capable in that line of study at that period of the world's history. Under him all the up-to-date apparatus was introduced for illustration and instruction. Professor Fairbanks was slow of speech but always held the close attention of the students.

Finally, William Alfred Packard gave us all the instruction we received in the modern languages studied at that time, namely, French and German. Fie was an accomplished scholar and a good instructor but we had all too short a time to pursue these languages.

In conclusion what shall I say of the instruction given during those four years in comparison with that which is now given in the Dartmouth curriculum in these last years of the first quarter of the twentieth century? What is education, anyway ? It is simply cultivating the mental powers and teaching the mind to think, and by thinking grasp new discoveries and assist in making them. Of course, Latin and Greek are the only two studies of that period that are indispensable now, and ever will be, to make thorough scholars and sound thinkers. That our professors did good work is manifest in the great and valuable work that their students accomplished in the closing years of the nineteenth century and the beginning years of this twentieth.

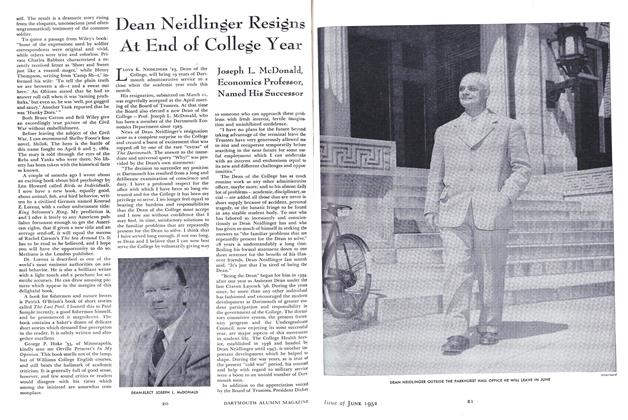

President Nathan Lord

A new view of Dartmouth Hall Courtety of the Pictorial

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1926 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1926 -

Article

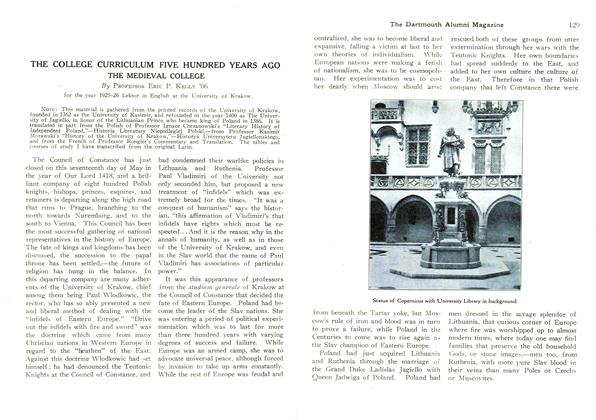

ArticleTHE COLLEGE CURRICULUM FIVE HUNDRED YEARS AGO THE MEDIEVAL COLLEGE

December 1926 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Article

ArticlePHYSICAL FITNESS WORK AT DARTMOUTH 1925-26

December 1926 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Article

ArticleC. F. RICHARDSON'S TRIBUTE TO THE GREAT PRESIDENT

December 1926 -

Article

ArticleWHY THEY DON'T ATTEND MASS MEETINGS

December 1926 By Harry R. Wellman '07