headlines for editorial articles in this publication, the title of this might well be "Noblesse Oblige." It is once again the season to assail in deadly earnest the problem, now recognized as a hardy annual, of the Alumni Fund. That Fund, as we have often tried to show, is the necessary concomitant of the present gratifying condition of the College. It is the price which has to be paid if we are to retain its growth and hot see it slip backward. It is the thing which noblesse obliges, so to speak.

By this time it should be quite unnec essary to explain the situation which every year brings to pass. We all know that even when the tuition fee is raisedas it will be another year— to $400, the amount which the individual student pays does not nearly meet the complete cost of his course. There remains a gap which has to be filled. Of course one might adopt the expedient of charging the full cost of education to the educated but that would mean making Dartmouth a "rich man's college" and no one is anxious to have that come to pass. Or one might, by frenzied effort, assemble an endowment fund temporarily capable of supplying the funds to meet the recurrent deficits by using the interest arising out of its investment. That in turn has been adjudged not to be practicable at present, although some day it may be more so than it is now. The Dartmouth custom is to collect from the whole body of alumni, graduate and non graduate, by voluntary contributions, a sum representing the interest on an imaginary endowment—which this yoar is designed to reach $110,000 in order to keep pace with the growth of the College, while at the same time recognizing the annually increased size of the alumni body. That body, which in current conditions enjoys a birth-rate far in excess of its death-rate, has proved itself able within a year to the task of raising over $90,000. ilt is now asked to set $110,000 as the goal and very hopefully to exceed it. That has happened before.

With the more intimate acquaintance of our alumni with this problem comes naturally a lessened necessity for emphasis on the salient points. Yet it is felt that some mention, similar to what has been made in past years, is not amiss—more particularly an emphasis on the desirability of promptness in responding to the call when it comes. One assumes that the situation is understood and further that the overwhelming majority both wish to give and intend to give, according to ability. The great difficulty always arises out of procrastination on the part of many whose intention to be numbered in the list is undoubted, but who, often for perfectly valid reasons, postpone—and then, unfortunately, forget.

There has come into being since this fund was first started a new species of class officer, known as the "class agent, whose, arduous duty it is to communicate with every member of his own class and assemble contributions. If every one answered at swered at once and sent in his pledge, the task would be comparatively simple—but naturally that never happens and is beyond the realms of possibility. The more frequent case is to withhold reply until one, two, three or even four followup letters have been despatched, which entails a heavy burden on the agent of even a moderate-sized class, not to mention an increased cost in postage and other things to swell the "over-head" and reduce by so much what the College finally receives. One hardly needs labor this point. It is obvious enough. The thing to do, reader, is take it home and act on it!

You, if you care enough for the College to be a reader of this MAGAZINE. surely need no pleading to convince you that this Alumni Fund is well worthy of your support. We are taking that for granted. All we are insisting on is the desirability of lightening the burden of your class agent, and the feasibility of cutting down the expenses of collection, by immediate action when the agent's first letter arrives. You needn't necessarily enclose a cheque, but at least you can without much bother give him an answer indicating what you propose to do. Writing that letter is going to take about so-much time anyhow, and you expect to write it eventually. Why not at once? It will save the agent a lot of work if every one will do this—really do it, instead of merely approving and meaning to do it.

How much should a man give? Whatever he feels with satisfaction to his own conscience he ought to give. One's own conscience is a pretty good judge and one not easily deluded by specious pleas. The satisfaction which flows from answering the dictates of a well-working conscience is tremendous in any properly constituted human being. Given fair luck, it seems likely you will be able to do at least as much as you have done in other years; and you may be well assured that the needs of the College have not been in any wise reduced, so that if greater abundance enables you to increase your participation this year it will be welcome indeed.

Every year we have appended a word, which we hereby renew, for the reassurance of those who are unduly modest and who seem to feel that a little gift would be disdained. It would not bevery far from it. The Alumni Fund committee has a dual ideal. It wants to raise $110,000, for one thing; and for another it wants to come as close to polling every living alumnus as it can, regardless of the size of the contribution. To have every wandering son of the College enrolled as a participant is the ideal—unattainable, to be sure, but capable of approximation beyond what has been achieved as yet. Many a man who gives a dollar, or five dollars, or ten dollars, gives as generously as many a man who gives one or two hundred. In fact we suspect that in such cases the generosity is often greater, as was once remarked by the Saviour in commenting on the relative value of the widow's mite.

There is nothing to patronize in all this. The loyalty which makes a man who can ill spare the money give a five dollar bill to the Fund, is often greater than that which makes a man who can perfectly well afford to give $5OO send his cheque for $lOO. One wants to come as near as possible to the ideal of enrolling every mother's son of our alumni, the world over, this year and every year.

Of course there is always the danger of riding the alumni horse too hard. Dartmouth alumni are not, as a rule, men of unusual wealth. There are acknowledged limitations to what we can do. The concern is to make a careful and accurate estimate, so that the maximum of achievement may be had that is consistent with our keeping it up. Fortunately the alumni body is growing fast and thus 'far its capacity and its disposition suffice to enable with some ease accomplishments which, had they been hinted at a score of years ago, would have been voted chimerical. What is here attempted is a reminder that, if we would retain what we are so honestly proud of, there can be no resting on the oars. The current would instantly begin to sweep us backward again. Neither can we very safely adopt a standard of stroke which will only just equal the resistance of the current—for that would merely keep us where we now are. There needs to be progress all the time, but progress of the healthy sort—which means a steadily maintained progress, proportioned to the reasonable strength of our combined fellowship, rather than sensational bursts of speed which must speedily languish and leave us an easier prey to the set of some counteracting tide.

Those who read attentively the pages of this MAGAZINE can hardly have failed to be impressed by the work done by class secretaries in providing news for the department in which such items appear. It is likely enough that to the average alumnus this is the most valuable feature of the publication and the one to which he turns with the greatest interest.

The volume of the material submitted is a monthly testimony to the industry and interest of class officers, who manage to find time for it despite their daily tasks of a purely personal sort. Secretaries vary, to be sure, but the great majority seem to be indefatigable in their quest for interesting information worth}' to be relayed to their classmates through this convenient medium of c ommunication. A good class secretary is a pearl of great price. Happy the class that finds one early and can induce him to retain the office. Of course there are conflicting theories as to the propriety of making such a job a matter of the secretary's lifetime. It seems about a 50-50 break between the two arguments, provided changes are made at least so infrequently that a secretary is not replaced just as he is beginning to be most efficient. The older classes seem more devoted to the life-job idea; but it has to be admitted that in the columns of alumni news there is quite as fervent a zeal displayed by secretaries whose tenure is briefer. How these devoted men manage to dig up so much material from sources so widely scattered will puzzle almost any reader. But they do it.

It is well to take a long look ahead before embarking on the current season's campaign to raise the Alumni Fund, in order to acquire a general idea what the special needs of the College are likely to be in the immediate future. During the past few years attention has been concentrated mainly on the needs of the salary list and the other similar items which figure in the cost of education, to meet which the Alumni Fund principally goes. It is now time to consider additions to the physical plant, which cannot longer be delayed if the College is to hold its own, but which have been postponed thitherto as a matter secondary to putting the purely educational work on a sounder basis. The reader is already aware that the trustees have voted to proceed at once to the construction of an adequate library building. It will be necessary also, within a very short time, to add to the dormitory facilities. It is likewise nearly as imperative to replace College Hall—which has not been adequate for several years as a meeting place for the entire student body—by providing a building large enough to fulfil the purposes for which this extremely useful building was originally designed, but for which it is at present wholly impossible to use it.

The result of this diversion of interest and funds to the needs of the physical plant will naturally intensify the necessity of the Alumni Fund as the main source of revenue to meet the deficit annually recurring in the educational budget. That element must be fully taken care of while the permanent equipment of the College is growing. We are still far from finally solving the educational cost problem. The present salary scale, for example, while much less unjust than it was a dozen years ago, is still very far from the attainable ideal. Dartmouth's rate at this time for a raw new-comer to the faculty is about $18000, and the salaries run from that figure up to $6OOO for a few of the older men. It is hardly to be doubted that these figures are still too low, both as lower and upper limits; and it would be extremely desirable, if we are to hold the best men we develop as teachers, to have the scale run from $2OO0—or better $2500—to something like $7500.

One thing we have done that permits us a bit of a rest, and that is the reduction of the ratio between faculty and students, so that at present we have practically one instructor to every dozen men, which is not far from the proportion stipulated by most of the "foundations" as required for adequate work. It may well be that our student body of about 2000 can be taken as a constant for some years to come, making it needless greatly to expand the present personnel of the instruction staff. It is, however, most desirable and indeed imperative to enhance the rewards of the instructors in order to keep with us the more experienced and valuable men as against the blandishments of those who would lure them away.

In other words, the already great necessity of the Alumni Fund is perfectly sure to be increased during the next few years as we are forced by circumstances to amplify the tangible plant of the College. Fortunately the circumstances which force this are such as every one is glad to know exist. They are the inescapable concomitant of the amazing growth of Dartmouth in prestige and repute, as well as in size. They grow directly out of success and as such are sources of proper pride. They are the price of prosperity, so to speak. In fine, our progress brings with it certain duties; and it is assumed that alumni everywhere will welcome such evidences of growth as a thoroughly healthy sign.

This is mentioned here as bearing on what will have to be done during the next half dozen years by the loyal graduates of the College, provided we are merely to hold what we have gained and main tain our position. The administrative policy, as we understand it, is to emphasize at Hanover the distinction between college and university. Dartmouth is not a university and does not aspire to be one. It recognizes the increasing tendency of the great American universities to centralize their efforts on the graduate schools and in proportion decrease their insistence on purely undergraduate departments. There seems to be a distinct field for the colleges as the natural feeders of the universities, and Dartmouth would very gladly be rated among the foremost of such institutions. To make at Hanover an institution which will be cordially recognized as a leading college among avowed colleges, rather than a feeble imitation of vastly greater universities, is the aim. A college we are, and a college we shall remain; but we would gladly be the best type of college obtainable, with the best possible equipment operating on the best of carefully selected material. The time for respite is not yet, if that is what we are going to do.

Recent investigations have developed the fact that the type of architecture adopted at Dartmouth is peculiarly efficient. It may not have occurred to you that the special style of building employed makes any material difference, economically speaking, but the differences are in fact extremely important and their extent is surprising. It is stated that the New England "colonial" type of building, such as ours, is vastly better suited to the needs of the moment than other familiar types—notably the Gothic so much affected by various institutions. A recent estimate is to the effect that a dormitory in the colonial style can be erected at a cost of about $2000 per student occupying the same, whereas a dormitory in the Gothic manner will cost considerably more and may exceed $9OOO per man. That is to say, a dormitory for 100 men can be provided in the colonial style for about $200,000 where one of another type for serving equally well a similar number of occupants may cost from three-quarters of a million to nearly a million.

Of course what new construction is done will seek the maximum of safety in the matter of fire-risk. Fireproof construction has made such advances in the past few years that the newer dormitories at Hanover may be rated as involving the minimum of hazard and most of the older buildings are at least of such construction as to warrant a belief that the risk is very small. The importance of this will be appreciated as one reads the annual accounts of serious fires in academic institutions—there are many such happenings every year. What Dartmouth plans to do is steadily to increase the facilities for students in ways which make for permanence and safety, as well as convenience. It is not proposed to scamp the business of building. What is built will be sound. It is therefore agreeable to find that the general architectural type which has been adopted for our buildings is at once harmonious to our surroundings, capable of the maximum of safety, and productive of the minimum of cost.

Speaking of the new library, it may be stated that during several past years the College has been anticipating the day when at last it would have adequate housing room, by procuring books.

These are now disposed in various places around town awaiting the time when they may be suitably arranged on shelves for the actual work of education.

A word as to what this involves. Among the interesting innovations which the modern colleges have introduced is the idea that the few glimpses o;f a given field which the classroom work permits shall be amplified by outside work, such as a proper library enables. It is ridiculous to suppose that in a few courses, such as a student takes, there can be

given a comprehensive view of an entire intellectual domain. One may study in detail a very few subdivisions of the field—and for the rest one must dig it out for oneself. The so-called "comprehensive examination" now so much in vogue means, as we understand it, that the student of the future must prepare himself to give evidence, not alone of what he has retained from his classroom work, but also of what he has been able to acquire of the general aspects of such a science, say, as economics, by supplementary efforts in addition.

One has moments of feeling that if one were required to attend a college now the prospects of obtaining a degree would be much less glowing than they used to be. Time was when one got anA.B. without much difficulty—largely by the process of being pumped full of information which an examination eventually pumped out again, if there were any left to pump. It is a more strenuous business, now that a student is to be held responsible for a great deal more than his professors have had the time to go over in detail with him. But one may hardly deny that such as pass successfully the sort of tests which a "comprehensive examination" affords really have to know something about the science they happen to be dealing with, whether or not it all remains with them vividly for the next dozen years.

tin memory of "Dick" Hall, late a mem ber of the present junior class, who died last year at Hanover, his parents, Mr. and Mrs. E. K. Hall of Montclair, New Jersey, have offered to in the vicinity of the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital a building to be used for the care of undergraduates who may be either seriously ill or slightly indisposed. The juniors will probably lay the corner-stone in June.

The building will be designed with the ide,a of making it more like a pleasant home than a hospital or an infirmary, so that students temporarily housed there may be in more cheerful surroundings than usually fall to the lot of the sick and will not be impressed by the idea that they are for the time entirely apart from the daily life of the College. The building somewhat inadequately denominated at present a "'health house, is to be connected by a passage way with the Hospital, so that at need the facilities of the latter may be called upon; but it will in itself be of the club-house type of architecture, in the colonial style, and should be a most welcome addition to the equipment of the College. Rooms will be provided for visiting parents, and a house-mother, or hostess, will be, in general charge. Present plans contemplate 40 beds, to be made use of in case of any indisposition, however slight, which makes observation a proper precaution.

Dick Hall died in his sophomore year, universally lamented. His father, Edward K. Hall '92, is one of the vice presidents of the American Telephone and Telegraph Cos., a former trustee of the College, and present chairman of the Football Rules Committee. There is no more loyal alumnus of Dartmouth, and none more intimately and affectionately known by the whole alumni body. Mrs. Hall, whose father was Irving W. Drew '70, joins in the gift, which is singularly appropriate and which represents something of which the College has long stood in great need.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT'S THE MATTER WITH FOOTBALL?

March 1926 -

Article

ArticleTHE BEGINNINGS OF ORGANIZED SKIING AT DARTMOUTH

March 1926 By Fred H. Harris '11 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

March 1926 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

March 1926 By H. Clifford, Bean -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

March 1926 By Ralph Sanborn

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH GATHERINGS IN FRANCE

January 1919 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

October 1949 -

Article

ArticleFaculty News

JUNE 1996 -

Article

ArticleReminiscences of an Old Dartmouth Stage Coach

DECEMBER 1929 By Frederick H. Burleigh -

Article

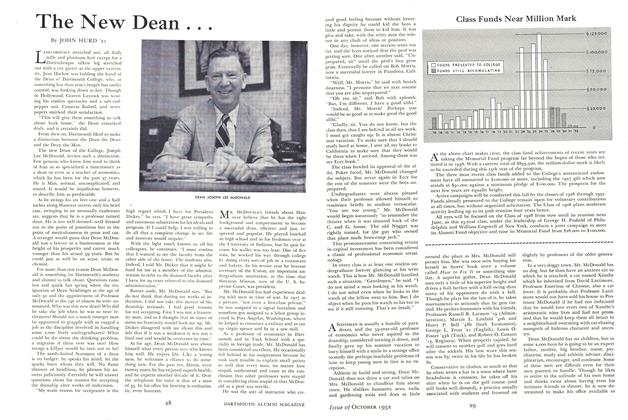

ArticleThe New Dean . . .

October 1952 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

April 1943 By William P. Kimball '29