Man and his Fellows: Lectures on the Henry LaBarre Jayne Foundation, Academy of Music, Philadelphia, 1925

May, 1926 C. D. AdamsMan and his Fellows: Lectures on the Henry LaBarre Jayne Foundation, Academy of Music, Philadelphia, 1925 C. D. Adams May, 1926

By Ernest M. Hopkins, President of Dartmouth College. Princeton University Press, 1926.

In his Foreword, President Hopkins disclaims the expectation of greatly instructing or persuading his hearers, but will be content with "stimulating speculation and leading to reflection." His ambition is well justified, for the lecturers are both stimulating and suggestive. Dealing in a summary way with questions which are much in the public mind, and which could not be discussed in detail within the brief limits of his time, he suggests leading principles, clears away misapprehensions, and emphasizes, and in his own treatment illustrates, the spirit in which such problems must be met. His attitude is frankly optimistic. He regrets "the prevalence in these critical times of a cult of pessimism from which it often is hard to get away." "This widely pervasive mood," he says, "has become more particularly a pose of the intellectuals. Sometimes it seems problematical whether among this group one can be thought mentally competent unless he radiates discouragement about the present, and despondency about the future, denies the fact of progress, and sneers at theories of self-determination."

The first lecture, under the title "Associationalism," begins with this thesis: "Society is in the precarious situation where to stand still is impossible, and to move without intelligent forethought may be calamitous. It is not a time for doctrinaire, dogmatic or selfsufficient thinkers or doers. It is not a time when the attitude can be condoned which reckons life in terms of what can be secured rather than in terms of what can be conferred. Selfcenteredness and selfishness have become not only impracticable but intolerable."

The lecturer dwells at some length upon the fact that in earlier times the comparative isolation of national groups made the mistakes or misfortunes of one or another of them less disastrous to mankind in general, while it was possible for the discoveries and betterments of one group, though in a somewhat slow and haphazard way, to infiltrate ultimately among the rest. But with the decreased size of the world in our day—with its quick communication and its multifarious interdependence of part on part, segregation of either nation or individual is impossible. Yet the specialization of work which marks our time makes it in some ways more difficult than ever for the man of one calling to appreciate the problems of other men. "Only by recognition of this fact and by deliberate attempt to offset it, calling ourselves continuously back to the needs of man as a whole, may we live with understanding, and with advantage to generations which, shall follow us." . . . On the negative side individual satisfaction and individual success can be sought legitimately only in such ways as do not harm or endanger group welfare. On the positive side man as an individual, in his capacity as a thinker and a doer, must be solicitous for and a contributor to the common life of society as a whole." Our problem is to "preserve the initiative, stimulus and interest of individualism and, at the same time, modify and adapt this so that it does not injure the association of individuals which we call society." The solution must be found in "a coordination of emotional force, religious interest and intellectual selfcommand that constitutes man at his best."

. The lecture on "The Need of Working Hypotheses" pleads for an intelligent formulation of working hypotheses in the field of social relations which shall be founded on exact observation and careful generalization, comparable to the processes which have given to the working hypotheses of physical science their safety and success. Science has long been able to reduce the stresses and strains of physical materials to exact formulae and to develop safe working rules; yet "it seems to have been only comparatively recently that there has been any consciousness in the human mind that civilization is subject to stresses and strains which can possibly be calculated. Hence the question arises, can we codify obvious facts sufficiently to draw up the formulae by which to judge to what extent society, can bear the pressure of contemporary conditions? Can we evolve the reckoning to know how to meet the strains that are put upon life today?" Warning of the danger of following the merely traditional view of social questions, the lecturer says, "The most fatal thing to the scientific spirit is the closed mind . . . We should not forego convictions, but we should hold these always subject to reexamination. We cannot tolerate the inertia which makes us decline to take into consideration the new factors which come to our observation."

Turning to the industrial question as the "most conspicuous phase of present-day social organization" President Hopkins traces the growth and transfer of absolutism first in the Church, then from the Church to the State, and finally with the industrial revolution from the State to the Economic Power. For a long time the whole attention was given to perfecting the mechanical instruments and machinery of production; they have been brought to marvelous perfection; meanwhile it is only recently that any corresponding attention has been given to the personal means of production. This is the outstanding problem of our time. What incentive can be given to the worker and how can his personal interest in his productivity be aroused? By the perfection of machine processes "pride or joy in work has been destroyed. It is necessary, if we are going to get the increased production which it is necessary that we should have, it the prosperity of the world is to be enhanced, —it is necessary that we should put back into industry somehow the stimulus and the incentive to work on the part of the individual. Real democracy will be achieved in our industrial system when conditions are actually established that insure the more capable men in the more responsible places and guarantee fair treatment and just wages to all. . . . Authority must in the very nature of things be exercised by management over productive force rather than the reverse, but it will be derived justly and utilized intelligently."

The third lecture, "Problems of Citizenship," is a plea for a more intelligent and active interest in public affairs on the part of the ordinary citizen. Certain tendencies are noted which are likely to make the individual inactive and to mislead his thought. The growing centralization of government removes its questions and its personnel farther and farther away from the knowledge of the individual; the tendency to administration through commissions and bureaucrats rather than through officers directly dependent on the people gives to the voter a feeling of helplessness; the rush of modern life and the attractiveness of its diversions, multiplied by mechanical invention, militate against the leisure and quiet reflection which are necessary to creative thought; "Blinding ourselves to our needs, we seek expedients instead of principles, and slogans instead of policies"; the spirit of truth is attacked as never before by original and misleading propaganda, with its "accentuated spirit of intolerance." "The resistance to all these gigantic forces which beat in upon the individual is futile except as this resistance is bred within individual men and is transmitted by individual men to society as a whole.' The training and inspiring of the individual for leadership becomes one of the greatest demands of the age. "We cannot too clearly l eep before ourselves the fact that leadership is not mastery, but that it is influence, and that no man can become a wise leader who has not been willing to be a wise follower; that in a democracy leadership ought to be conferred by the confidence of the people at large, and ought not to be won by specious arguments or permanently secured by self-appointed guides with selfish motives. . . . Certainly democracy cannot reasonably claim proved superiority among the principles of government in the earth until it can with some certainty bring its best men. up to the positions of leadership, and can produce a following which recognizes and accepts wise leadership when it is providentially afforded." While President Hopkins shows throughout that he is to be classed with the liberals, he is not unaware of the dangers which beset the liberal apostle: He warns of the tendency among those who are pleading for social justice to ignore new evils that may take the place of the old: "This tendency is all too frequent among men who are giving anxious thought and interest to the affairs of those, to whom social justice has been long delayed. This tendency leads to condoning abuses and bigotries among those for whom this new concern is felt, though these will be as detrimental to society, in the long run, as are those older faults against which protest is being made and fight is being waged. . . . The liberal can least of

all afford to become unreceptive to the possible truths involved in the thinking of others. The mind willing to consider the validity of opinions not its own, and open to conviction in the presence of new knowledge, is more liberal than that of the bigot, regardless of the professionalized attitude which influences the beliefs of either,"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWATER FOR HANOVER AND THE COLLEGE

May 1926 By Robert Fletcher -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1926 By L. J. Heydt -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1926 By L. J. Heydt -

Article

ArticleBalloting for election of alumni councilors is now in progress

May 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

May 1926 By H. Clifford Bean -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH GREEN

May 1926 By The Rev. Roy B. Chamberlin

Books

-

Books

Books"Ruskin The Professor,"

December, 1928 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

DECEMBER 1965 -

Books

BooksThe Underside

October 1980 By A. Roger Ekirch '72 -

Books

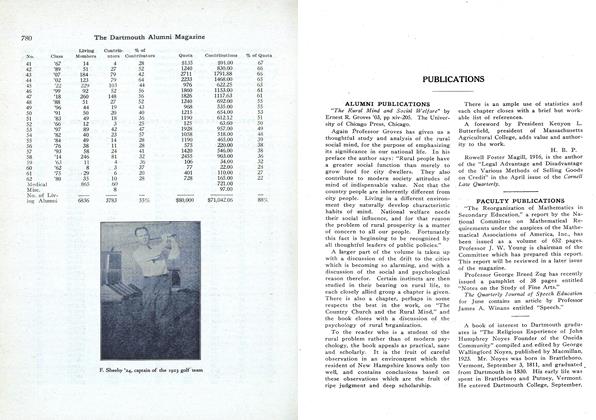

Books"The Rural Mind and Social Welfare"

August, 1923 By H.B.P. -

Books

Books"Composition and Literature"

July 1918 By Kenneth Allan Robinson. -

Books

BooksTRADEMARK PROBLEMS AND HOW TO AVOID THEM.

JULY 1973 By KENNETH R. DAVIS