The Opening Address

President Hopkins' opening address to the College is always a stimulating affair, but never has it been more so than this fall when it devoted itself largely to the theory that, in addition to training up intelligent leadership, the American colleges should also seek to inspire in the great body of young men and women coming under their influence the power to know good leadership when they see it, and the discriminating desire to follow it when it be found. That seems to be saying that we need not merely good leaders, who must necessarily be few in number at any given time, but also a disposition in the many to be led by the right few. It has long seemed to us that this element in the problem should be more often stressed.

The present estate of American politics is likely to inspire in any thoughtful mind a doubt whether the broad general public of the country has in fact that power of wise discrimination on which democracy must ever depend for the attainment of a tolerable result. At all events there has been a growing debate of the question whether or not democracy is proving a failure, with no lack of native-born advocates ready to assume the affirmative. Curiously enough, a recent public discussion in Boston revealed as the defendant of democracy a well known representative of the British aristocrats, arguing against a well known American author-professor who might well be cited as, in his own career, one of the proofs that democracy was capable of succeeding. None the less it is true that democracy is a matter of averages between popular wisdom and folly; and that, in order to make the average a tolerable one, the public making the choice must be brought to a sufficient pitch of intelligence and desire to enable it to know, so to say, the weeds from the wild-flowers, and choose the latter as against the former. To that end the colleges can, and we hope do, contribute by increasing annually by several hundred thousand folk the numbers capable of knowing a good leadership at sight and of wishing that leadership to do the leading.

Should They Pay In Full?

The college world may as well make up its mind to face the vexed problem which grows out of the fact that students at present pay, in tuition fees, only about half what their education costs them. One may call it "about half"—but we understand that in practice it is really somewhat less. Is that right, merely because it is usual?

On the face of it, and speaking abstractly, it isn't right at all. Logically, there is no more reason why a man who wants a college education should get it for half-price than that he should pay only half what his suits of clothing cost. Education is practically the only thing which is being operated on a frankly eleemosynary basis.

Speaking more concretely, there are of course certain offsets which are invariably urged to justify the current situation with respect to college tuition fees. It is always asserted-that making the tuition cover the actual cost would confine higher education to "the rich" and would make it impossible for the poorer student (who is very .often the worthier object of higher educational efforts) to consider college at all, save in some of the State universities where tuition is virtually free at the expense of the public. The acute question is whether or not this objection is valid; whether or not it outweighs the obvious desirability of having those who derive the benefit pay the cost, precisely as they would do in the case of any other purchase.

The younger Mr. Rockefeller not long ago came out flatly for the idea that allowing every student to obtain an education at half price, or less, the residue being made up by income from endowments or alumni funds, is vicious and wrong. He would have the actual cost charged to the man who is educated—perhaps payable in later life, beginning 10 years after graduation, but payable by himself and none other. Admittedly there would be need for great liberality in the provision of scholarship aid, student loan funds, and the like; but, if we understand Mr. Rockefeller's contention, he would make the discharge of this loan an individual matter with the student educated, and not treat it (as in so many cases it is now) as a gift toward meeting a tuition fee which itself covers only about half the actual cost.

From the purely logical standpoint, as we have intimated above, it seems impossible to assail the soundness of this general proposition. There really isn't any apparent reason for selling education at a ruinous bargain rate, unless it can be shown that charging exactly what it costs is going to debar from education many who would make good use of it, the while it makes college training a perquisite of the idle rich. Mr. Rockefeller asserts his disbelief that it would do such a thing, citing the fact that recent marked advances in tuition charges in various colleges (Dartmouth is certainly one of these) have had no deleterious effect on the quality of the students applying to be educated. He appears to believe that a slow but steady advance in the rates, say by steps of $50 a year, to the point where a virtual parity would exist between payment and cost, would produce the desired result without appreciable hardship.

Dartmouth's present tuition charge is $4OO a year. It would need to be much greater in order to equal the cost per man. The present fee, although double what it was a few years ago, has not made any appreciable change in the complexion of the student body. Would it be feasible gradually to increase the charge, approaching ultimately the state where a man who wanted a college education must pay what it costs, just as he must pay for everything else?

It is certainly not a matter to be decided hastily, or on the basis of rash assumptions. It needs to be, and will be, considered most devoutly and soberly by college administrators—but it is apparent that as a matter of first impression the opinions of such are divided. Agreement may be impossible. At least it is evident that charging the full cost of education to every man educated, regardless of his means, exactly as he is charged for a ticket from Boston to Chicago, or for a dozen shirts, would tend to confine college education to such as wanted it badly enough to pay for it, instead of making it a sort of gay adventure.

Before taking any definite stand, most of us would prefer to hear the question exhaustively argued; but it does seem as if the burden of proof should lie on those who deny that the logical course—that of asking the recipient to pay in full for what he gets—is the right one to follow in the future. The situation which exists now is an inheritance from the time when the colleges were frankly charitable institutions, supported by religious or philanthropic people with intent primarily to educate poor but worthy young men for the pulpit. Colleges are hardly that at present, but the charitable phase of their existence dies hard.

In many, if not most, of us a certain inherited prejudice will have to be overcome—a prejudice which makes education a sort of sacred thing, which is not subject to the same conditions that beset other transactions. The question suggested here is of the validity of that prejudice. It may be justified, or it may not be. The presumption of abstract logic seems to us to be against its validity, although we should be slow to hold this presumption to be immune to rebuttal. Let us sum it up by asserting the belief that a student ought, to pay in full for what the college sets before him, unless there can be shown some clear reason why he should get half of it at the expense of someone else. The latter is what he is doing now, but is it really right ? Is it really necessary? Or do we only think so because that is the way it has always been?

Analyzing The Colleges

There has been something very like an epidemic of analytical articles in the periodicals of the United States during the past few months devoted to the problems of the colleges. It is not at all strange that this should be so. In addition to the obvious temptation toward the exploitation of this topic, as afforded by the amazing growth of the numbers of students, is the cognate question, raised by virtually all the authors who contribute these articles, whether the movement is worth while. There are a hundred students now where in former years there was but one. The total college population must at present be somewhere between 800,000 and a million. The expense is prodigious, and the net effect produced is held doubtful to the extent of making many inquire whether the expense is justified. Do the young people who flock in such hordes to the scattered colleges of the land get enough out of it to pay? Are the colleges doing what they should to winnow the good material from the bad? Ought a young person to be encouraged to go to college, or be discouraged from going? What should be the aim of higher education, anyhow? The number of queries suggested is great and the answers are almost as various as the questions.

If the theory of the present administration at Dartmouth is correctly understood, it is that the great end to be served by the American colleges (as distinguished from universities and technical schools) is to improve the intellectual, moral and ethical estate of the American public, as far as that may be done among such multitudes of immature men and women, well knowing that the very numbers involved impose an insuperable handicap against making erudition of an exceptional kind very common, but nevertheless appreciating the value to the country of such efforts as circumstances do allow. That every high school pupil should be encouraged to go to college could hardly be maintained. That some should be discouraged for their own good and for that of the colleges is clear. "It all depends" on the individual—and generalizations are worse than dangerous. They are impossible.

That the magazine writers, whether favoring college education for the many or opposing it, will settle anything whatever seems doubtful. It may help to clarify the discussion, however, to have so much written and printed. Out of it is likely to come a well diffused idea of what the circumstances permit American colleges to do, and of what the country itself really needs most.

It is at least time we outgrew the indefensible notion that there is a clear analogy between colleges, such as are now so numerous in the United States, and the ancient universities of the old world. It is also time a better differentiation were made between the purely "liberal" colleges and the universities in our own country. Still further, it is time that not only the colleges, but also the parents of boys and girls, should recognize the futility of assuming that, because higher education benefits one it must necessarily benefit another. To a great extent the custom of going to college is the result of mere fashion—another thing that is being more and more candidly stressed. Properly equipped young people with proper reasons and proper aspirations should certainly go to college—and no others. All of which it is easy enough to say; but the establishment of what constitutes proper equipment, proper aspirations and proper reasons may be a more difficult matter.

If one may say it without inviting scorn, and emphasize it with a proper reverence for whatever is good in democratic institutions, there is a danger already manifest that one effect of democracy is to lower the old cultural standards. An outspoken Boston philosopher once expressed the fear that "America would eventually vulgarize the world;" and if he were living now it is quite probable he would add that his fears were being realized by the recent experience of the older nations. One may or may not accept that statement; but it is a reasonable contention that to safeguard ourselves it is well to come as near as we can to leavening the whole lump by insisting on the nobler and finer uses which a modern American can make of his years and opportunities. Scholars, in the higher sense, are wont to sneer at the smattering which half-interested, or largely indifferent, young people are willing to accept as the price for their four years in a pleasant atmosphere. Cynics, like Mr. Mencken, are heard to say that "what college students learn today is not much—and that little is untrue." Yet it remains a problem peculiar to our age and national condition, which we firmly believe the colleges are slowly learning to solve in the face of much misgiving. They are striving to enlist for the service of the United States an army of right-motived young people, far too numerous to be polished into- great individual brilliancy, but hopefully numerous enough to make them collectively a force for the upbuilding of an enlightened nation. Leisure is increasing among us. Wealth accumulatesand it is imperative that men shall not decay. It is more and more easy to worship Mammon, and more and more difficult to worship God.

If the vast sums spent annually by the people of this country for the college education of their young be no more than an insurance against the inroads of vulgarization, they may be well spent. The insurance is only partial, but it is apparently all we can look for.

The Bells

One of the most interesting, because wholly unusual, of the recent gifts offered to Dartmouth College is that of a comprehensive chime of bells for the tower of the Baker Library. In a way, such an adjunct is in the nature of a luxury; and in a way, one should hasten to add, such an adjunct is capable of fitting itself so appropriately and importantly into the college picture as to constitute one of the most enduring of practical blessings. One has but to reflect on the part which bells have played in past history in order to convince one's self that there is much more to them than an idle clamor of metal against metal, as certain of our poets have well and truly said. The carillons of Americaand they are increasing in number—may in time rival those of the older hemisphere, not as mere diversion for the casual ear, but as the symbols of, and inspiration to, something higher and better in the casual mind.

The suggestion of such a chime for the college towers has figured among those which President Hopkins has occasionally outlined in his addresses to alumni groups and to the Alumni Council. It has been one which most of us probably regarded as interesting rather than of immediate importance—one likely to be realized only after the lapse of many years. Instead it comes at once, before many things of more obvious and more directly material importance to the worka-day business of education. Do not, however, make the mistake of assuming that it has not a high importance in its own peculiar way. It is the sort of gift which must work its miracles through the emotions, rather than the mind—through the heart rather than the head—but not for that reason less .vital to the future of the College and its sons. One welcomes a gift which is not mere bricks and mortar—one which has nothing directly to do with the daily efficiency of the college plant, but everything to do with the non-materiaf, which, one must always remember, is our great and ultimate goal. In this age of the world it may be that we make too much of materialism and too little of the soul; too much of the visible aids to knowledge and too little of the emotional aids to power.

According to the published announcements the Dartmouth chimes are planned to include fifteen bells, so that possibly it may be injudicious to refer to the installation as a carillon, although primarily a carillon is understood to mean a set of harmonized bells hung so as not to swing but to be struck by a hammer while in a fixed position, the hammer being actuated by someone at a keyboard. The modern American carillon, like the older one of Europe, generally contains from 25 to 40 or more bells. On the other hand the ordinary chime contains only about a dozen. With a set of fifteen bells, carefully cast and arranged in the series of the chromatic scale, it is possible for the skilled performer to play excellent music, though of course not so elaborate as the compositions played on the more comprehensive array of bells involved in a carillon proper.

The Autumn Council Meeting

The meeting of the Alumni Council held in Boston in October was notable as calling forth the usual large attendancetwenty-one out of the total membership of twenty-five. This sustained interest in the Council is a commentary on the loyalty of its components and on the wisdom of the regional choices, which so generally fall on men who can find the time to attend the meetings in October and in June, even when held at great distances from their homes. It is no small task for members to come, as at least three did at the recent meeting, from so far afield as California, Colorado and Oregon, not to mention Chicago, Cleveland, Washington and other points well removed from Boston.

The Council, as has been explained many times, is at present a sort of representative assembly, to which is delegated the list of duties once supposed to be performed by the Alumni Association at its general meeting at Commencement, but which the increasing number of the duties and the enormous growth of the alumni body have made it impracticable to perform save by some system of delegation. It is, in short, an almost exact parallel for the course taken by American democracy in its universal resort to representative government. The time when such affairs could be handled after the townmeeting theory by great general assemblages has clearly departed forever; and the Council, chosen to represent as well as possible the entire country, section by section, is the one feasible answer. The necessity of making wise selections of the representatives is clear, and wisdom includes in this matter not only the selection of far-seeing loyal alumni, but also such as can usually manage to attend the sessions. Twenty-one out of twenty-five is a very creditable showing—and by no means an unusual one.

The detailed report of the meetings will be found elsewhere and need hardly be commented on here. The Alumni Fund committee was authorized, and we believe wisely, to retain its last year's figure for the total to be aimed at-$115,000—instead of attempting to increase the same. The custom of retaining in the hands of the Council a final decision as to the personnel of class agents to solicit the fund was adhered to, and this also seems wise.

An interesting suggestion of a possible western Pow-Wow next fall, presumably at the time when a football game in Chicago would make likely a general pilgrimage to that city, was taken up and favorably considered. Whether or not this will imply a holding of the fall meeting of the Alumni Council at Chicago, as once before on a very similar occasion, was not determined but was postponed to the decision of the meeting in Hanover next June. It may be said that in general the Council welcomes the opportunity now and then to hold its movable session in the heart of the country, as reducing the burden on far-distant members; and above all approves every project which will tend to make the College and its affairs more real and more vital to those who cannot often make journeys to the East. "

Mr. Charles G. Dußois '91, whose term as an alumni trustee is expiring, was nominated by the Council to succeed himself—a fitting recognition of his record as a member of the Board.

The Football Season

By the time these lines are printed the football season of 1927 will have passed into history. At the moment of writing them there remains a game to play Cornell, at Hanover—but the record as it stands is much more gratifying than that of a year ago. The tendency now is toward a longer list of "hard games" during the season, which latter by recent practice is a full week shorter than that of more southerly colleges—that is, the tendency is toward the making of a schedule in which every game is important, rather than one composed in great part of minor games amounting to local practice without giving a real test of the Dartmouth team. It is needless to go into the record of scores, which will be found printed elswhere, further than to say that the one defeat thus far chronicled is that inflicted by the extraordinarily strong Yale eleven at the Bowl a week after Dartmouth's decisive defeat of Harvard in the Stadium.

As in so many recent years, it is a renewed pleasure to speak of a team so competent in sport and so creditable in all other ways, such as scholarship, morale, and sportsmanlike behavior. For this as in other years much is owed to the fine qualities of Jesse Hawley, chief coach and source of unfailing inspiration. It is well when the scores are in our favor, but best of all to feel that in Hawley's teams we can be sure of finding a genuine Dartmouth squad, animated by the best ideals of intercollegiate sport, without a man on it as to whose eligibility or standing there is the slightest question.

Rumors of Mr. Hawley's coming retirement have been published and thus far have not been confirmed by him. It is no secret that the devotion of so many weeks to sport by a man whose business concerns are engrossing entails a sacrifice; but there is an undoubted hope in the breasts of alumni appreciative of sterling work that Mr. Hawley may not find it necessary quite yet to turn over the leadership on the football field to other hands.

The Hockey Rink

Developments in the physical plant of the College are being announced so frequently in these days that the alumnus living at a distance from Hanover finds it difficult to visualize the changing scene. Now announcement has been made that the trustees have accepted the proffer of a gift of a covered hockey rink. This will be welcome news to the increasingly large number of those interested in ice hockey. At present, and with admittedly inadequate resources, hockey rivals basketball as a winter form of athletics. With the facilities promised by the new rink it is altogether likely that hockey will become the major athletic interest of the winter months.

The further extension of the gymnasium plant to the east, balancing the Davis Field House, will doubtless enhance the artistic appearance of the whole and in its supplementary use as a large auditorium it will be meeting a most difficult college problem.

There will be undoubted alumni gratitude to the anonymous donor who has made the rink possible and to the trustees for their action in arranging for the construction as quickly as this can be done to advantage.

The Late Irving French.

Of many Dartmouth men it has been said that the College was their religion. This statement has been intended in no way to detract from the mystical side of any particular individual. It simply means that the College has bred in the man a basic love which has lasted through his entire life and made him willing to do everything he could to promote the interests of the College and protect and preserve her good name. This devotion has been totally unselfish and has become a very part of the nature of the individual who possessed it.

Irving French was that sort of man. Dartmouth College represented to him one of the great ideals in his life and the associations which it brought were a natural and sacred part of his every-day life. Therefore, it is not surprising that when he died he made a provision that one-half of his entire estate, after the termination of two life interests in the income, should be paid to the College. This was just a natural expression on his part of his very great interest and love for the College. Very few, even of his intimate friends, knew that he had made this provision. It was not a thing for him to talk about because he did not seek any reward for the work that he did for the College, in the form of personal recognition.

We venture to say that it is the accumulation of gifts of this sort which will mean a large source of income as well as fundamental security to the College in the years to come. There will, however, be few men as steadfast and as disinterested as Irving French. Other men may make greater gifts to the College because their means are larger but no gift will carry with it greater depth of affection than that which characterizes this bequest of Irving French.

There will be many an expressed intention on the part of alumni to remember the College in this way and yet such gifts will not materialize. Irving French took good care that when he passed on, his offering to the College would be absolutely settled and the machinery for its securing ultimate possession of this property be absolutely secure. Along with love went wisdom and foresight.

We therefore want every Dartmouth man to know of this gift because it typifies something that is priceless to the College and which a mere expression of gratitude can never cover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHOMAS W. D. WORTHEN

December 1927 By One of His Sons -

Article

ArticleFACULTY MEETING

December 1927 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

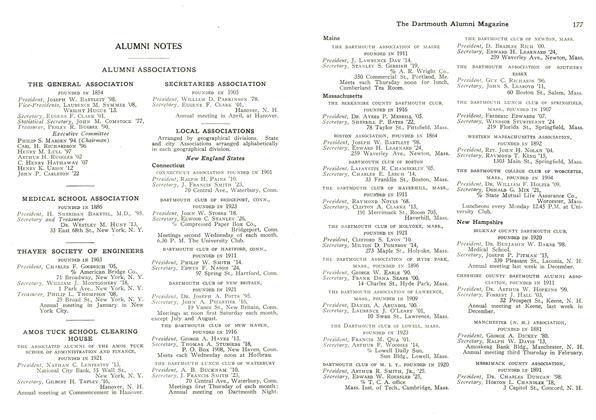

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December 1927 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

December 1927 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

December 1927 By Herrick Brown

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

January, 1926 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JUNE, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEDITORIALS COMMENT ON THE PRESIDENT'S OPENING ADDRESS

November, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter From London

May 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters

June 1945