Dartmouth Recruits in the King's Royal Rifles Are Training in England for Infantry Service

THIS IS THE QUIET HOUR, just after tea, but three of the boys are practicing the slow march on the barrack floor, with a friendly corporal saying, "By the quick march, hate, height, hate height no NO you're all out of step!" We've been drilling two days, and our heads are full of "quick march, left turn, hold your arms down, bend your wrists, Gor blimey you look like a—guardsman, get in step you bloody—." Also rifles with a 15-pound trigger pull, and we have to load a Bren gun in 6 seconds. Old Brister just jerks to a stop and nearly falls over backwards, with Durk roaring. So the corporal marches Durk into a stove. What a comedy.

The trip over was like a ferry ride. We left that certain Atlantic seaport after four days of rain in that certain dull city sailing on a pleasant (censored) which carried also the five of us and four other lads coming to join the war. One was Gordon Pope, who used to live in Old Greenwich; another was (censored) a small and fabulous French chemist going to join de Gaulle. It was a great big convoy, (censored) and well protected by corvettes, destroyers, and a plane a day for the last few days. We stood two-hour watches every day in the danger zone, at the machine gun posts on the bridge: but no Nazis. We didn't see a sub, a plane, or a mine. One night they dropped a few depth charges, but no dead U-boats uprose. So we read, several books as the journey took several days (15), and gambled.

The people in England are incredible. With barrage balloons over their heads and great piles of rubble around them, they grin and go to the pubs and curse Jerry with the conviction of people who know they'll win.

We have been made the center of attention; the 6oth is the only regiment in the British Army which has been allowed to enlist Americans. The corporals invited us to their dance Saturday night at Bushfield, which is one of the army's model barracks, set high on the downs a few miles towards Southampton from Winchester and only 5 or 6 miles from a famous body of water which separates England and France. Sunday we met Sir John McClure, Colonel Commandant of the depot battalion, who gave us the keys to the city in a pretty hands-across-the-sea speech; and our 1 Company O.C., Captain Barin, who told us some history:

Founded in 1754, actually the regiment of Rogers' Rangers (we wear the green caps of "Northwest Passage") motto Celeret Audax, and to live up to it we march 160 paces per minute (average regiment 120) and have 71 battle honors—Louisburg 1759, Peninsula, Delhi, Ter-el-Kebir, Afghanistan, Punjab, South Africa, Egypt, Boer, Flanders, etc.—more than any regiment in the army. As for Audax: two battalions of the K.R.R.'s and some battalions of the Rifle Brigade and the Victoria Rifles held up two panzer divisions for four days at Calais and allowed the B.E.F. to get out at Dunquerque. Thirty of 2000 King's Royal Rifles got out. A battalion held up the Adolph Hitler division for two days in Greece, then was wiped out in Crete. Another helped a battalion of the Rifle Brigade capture 15,000 Italians. We do all the tanks' dirty work—go in where they can't penetrate, fight rear-guards, cover flanks. We have terrific fire-power, move fast, have a special drill and in 7 months the five of us have to do recruit training, non-com's instruction, learn rifle machine gun, motor, wireless, command, interior economy, motorbikes, scout cars, lorries, etc. It is of course terribly exciting and we love it. But we work hard and I am making an awful mess of myself at the Bren gun, at the 30 inch pace, and at the moustache I am growing.

The pay is bad—s3 a week now, only 19 lb. on commission. If you can spare some cash, Dad, have your bank deposit to my account at Lloyd's Bank, Winchester branch. Then you get the benefit of the exchange and save time and U-boats.

None of us ever walked in step, stood up straight, went to bed early, got up when it was half-dark, or listened to lectures before in our lives. Undoubtedly this is a salutary change for us; actually, it is a great bracer and a fine thing, but it's damned difficult. The 60th has a hell of a fast step, that 30 inch pace means that I get knots in both thighs and hardly have time to lift my feet off the ground. And the gun-handling itself is fast and tricky. One maneuver, called the march-at-ease, is a battle honor won by this regiment alone for storming the gates of Delhi—and requires you to bring the rifle from the trail (we never use the slope arms) to the left shoulder with the muzzle pointing ahead. We nearly knock each others brains out.

We went to town about three times last week and had quite a good dinner at the Westgate or Southgate hotel for about three shillings. Pay being 15s and a slight glass of stout after dinner running you tod—we can't do it often. Flicks are about a shilling and down here they are just getting "Philadelphia Story," "The Bank Dick," and lots of pictures like Dick Foran in "The Mummy's Hand." London has just got "Lady Hamilton" (They don't dare call it "That Hamilton Woman" over here). They also refer to "The East Side Kids" and "The Bank Detective." GWTW is in its 1200 th performance; there are about a dozen plays, a couple of ballet companies and a concert by the London Philharmonic every night. This is all 60 miles too far away for us, of course we miss music badly and think of chipping in on a radio. The transport problem is also acute. There are infrequent busses to Winchester and a three mile walk at night after a day's drilling is practically a death sentence. Gas is severely rationed, 2 gal. each week, and the officers ride around on motorbikes, secondhand copies of which are available for 20 pounds or so if you can find one.

Our feet haven't blistered, but we all have Achilles-tendon trouble from the place where the boot bends in. The uniforms are high-quality however, and the socks and boots are fine, outside of that one trouble. We got tetanus and typhoid innoculations yesterday and have stiff arms today.

But yesterday was great—we met Winant! A sergeant popped in after lunch and said "All right, be in your best suits by 4:30, wash behind your ears and report to the detachment office. You're going to tea at the Deanery. Oh, yes—the American Ambassador wants to see you." An order, not an invitation. We were pretty thrilled and made it on time. (The Army has changed my way of life.)

Our wonderful Lieut. Richie took us to the Cathedral Close, beautiful centuriesold courtyard with great trees, narrow stone gate, the great pile of the Norman Cathedral looking up behind a sturdy old stone house. Inside a dark hall—then a dazzling green lawn, a lawn-tennis court far back, a pleasant terrace, and coming forward to meet us—the great man himself, accompanied by the little old fish-eyed blackgaitered Dean of the Cathedral. Winant is as impressive as they make 'em. Shaggy, jutting eye-brows, black unruly hair, black suit, firm handshake, amazingly like Lincoln in looks, speech and manner.... terribly shy, terribly sincere, wonderfully interested in us. He hadn't heard about us from the McLanes but had gone down for the day to Southampton, was invited to tea by the Dean, said he wanted to see us when the Dean told him we were here. He was even more cordial when we gave him the McLanes' messages, and insisted we come up to London for a week-end with him. The dean didn't have enough tea to ask us to stay, so he led Winant away after about ten minutes' intense talk; and Winant turned around, came out to us and said, "Isn't there anything I can get for you in London? A toothbrush or anything?" What a good man. He said he'd seen Herbert Agar the day before, and would tell Agar I was here. Agar arrived this week and has made a great hit, especially with his speech on Friday telling the British not to be so polite but rather to hurry us into the war. Winant said it was a good speech, but he was afraid it would get the British hopes too high.

The army is a great thing for us. It breaks us down absolutely, destroys the personality and poise we've built up, shatters our complacent acceptance of a comfortable world and an accessible bankroll, knocks holes in our easy confidence and shows us our lack of coordination, manual skill and ability to make our own way. Then, at its best, it builds up our coordination, shows us the importance of mutual trust and private responsibility. We have to have our confidence shattered by this drill, endless shouting, saluting, getting places five minutes beforehand—all the corn we instinctively and traditionally despise. Then we can get skills on an honest basis—our own accomplishments instead of the happy accident of birth—though of course, getting a commission still depends on birth and bankroll, but most of these officers know their stuff.

This is the best thing for all of us; especially for me. The only thing we have to watch out for is that we don't lose our personalities in the process of being revolutionized, or at least modified. Army wants initiative and enterprise—more so today in this mechanized army, where a section commander is a tactical leader on his ownthan ever in your Army days, I should think; but they don't care how they rub off the bumps that give individuality. We need fibre to stand up under the buffing and breaking down, strength to rebuild good soldiers out of our old selves, and resiliency and resistance to be re-formed without being de-formed. I don't mind losing poise now if I can come home a truer and better integrated man. I figured this out while gobbling a meat pie Sunday dinner just now which ought to excuse any indigestible pomposities you find in it. Keeping bowels nicely open, mouth shut as per instructions.

I took the welcome gold you sent me and went straight to London with it, but could spend very little. Durk, Jack and I got 48 hours leave Friday, were marched 3 miles to the station in the rain, had an overdue train up to London, and then our troubles stopped. We went to the Dorchester and were taken over by the U. S. Army. L. (a relative in London—ED.) and his fellow Colonels greeted us as if we were the 7 lost tribes of Israel (which we felt like) and wined, dined, slept and bathed us for two days and nights. They all had double rooms so we moved in, one Rifleman to a Colonel; we had hot baths for the first time in several weeks; we dirtied up towels, had breakfast in our rooms, drank G. Washington instant coffee (the only good coffee we've had since we left), went to Simpson's for direly rationed roast beef (but delicious), drank Scotch, slept late and between sheets, and especially enjoyed good plain American talk, common sense, and the sight of Americans drinking in a smoky hotel room. L. left his office Saturday noon for the first time since he got here, and took us every place, including a Chinese restaurant with marvelous chow mein, pork strips, lobster globs, etc. He was very rude about the checks, and hogged them all. He and the Colonels never offered us a cigarette; they handed us packages at a time.

L. is a remarkable fellow. He has great keenness and a terrific sense of balance mixed up with his generosity and compassion. He's all for our coming into the war now, but he always says we'll do it when the people get ready and not before. And L. confirms Dad's remark that once we get into full armament production we'll astonish the world. Even Knudsen says it'll be limitless. Well, if L. gets home before I do, give him a huge party. He says the war may last 5 or 10 years, but I'm not to worry about the future. "You've done the right thing and that's all that matters," he said. "I thought you were pretty unsound when we talked last summer, but you've certainly made the right move now." Which was nice to hear, so honestly said.

London is incredible. The damage is worse than any of the reports. You must imagine downtown New York, say from the North River in to the Wall Street area, just flattened, bricks and rubble in great heaps, and the office-buildings on lower Broadway gutted out with fire. Then up through the 20's and 30's there are burnt-out blocks, and around Times Square a theatre or two on every street caved in, and brownstone fronts gone in the 50's showing pictures and mirrors still hanging on walls. That's about the way London is: The East End docks and the city a shambles, West End places cratered every so often, stylish shops on Park Lane blasted out. And at night on Piccadilly the tarts (hundreds of 'em) and the soldiers and the cabs rush around in the blackout, people moving and talking in total dark, cigarettes for tail lights, and every so often a curb to trip over, or a crater with a fence around it.

Meanwhile everyone is cheerful, Piccadilly Circus packed with people like Times Square Saturday night, officers and soldiers of France, Netherlands, Poland, Canada, all over, (your arm drops off from saluting), theatres and movies running, concerts, and complete confidence. I don't think they can be licked.

Down here things are going better. We're getting the rhythm and actually liking it. The drill is tough, and the Bren Gun getting complicated, but we're catching on. Our new sergeant is great. He calls us "my five lease and lend pennies."

We had another basketball game with the gym teachers tonight and avenged ourselves. We got a little teamwork, played as rough as they did, kept our breath much better, and licked them 19-16. Guess who was Frank Merriwell? Bolte! For the first time a 88 star, I tied the score in the last minute with a swish from the floor and sank the winning basket 30 seconds later.

I understand we can't ask you to send us things, though the American Embassy offered to write the Censorship for us. But you can send anything you like, or think we'd like, as long as we don't solicit it. How's my old friend, Col. Hershey? And what about Jack Frost, the Domino Kid? And Mr. Heinz's dainty girls? I'd like to see them all again.

We have met some charming people in Winchester. One family has had us in to dinner twice. The lady is active in war relief, and was much interested to hear about your work. She said they absolutely would have been lost without the American help. There were no clothes, no bandages, no nothing; and then averything came from America, and things went on.

It's only 9:15 but I'm dying for bed. Imagine!

My last letter from Dad has notes all over the back of it on blister gas (Mustard) vapor—not felt at first—eyes go in 24 hours. This is a pretty serious affair, and you never go to sleep at these lectures. To think that we had to pay at Dartmouth, and now they pay us. But we listen as if it were a matter of life and death.

Rifle's going well. I got 18 out of a possible 20 last time—second best in my squad of 30.

I also made 2 mistakes out of a trials on the Bren gun today. I'd love a family portrait.

We had our first air raid alarm yesterday. I heard it going in to tea, and asked a corporal "Is that a raid?" "Yes," he said, simply. We went on in to tea.

The M.P.'s are squealing about bad blackout so here we go.

(Army No. 6854911)

Today our dear Sgt. Holmes told us he's recommended to the O.C. Company that we be made lance corporals next week and go each with a squad to help instruct. This is pretty fast, I gather, as we've only been training four weeks. We finish our recruit training tomorrow week, and then have five weeks to wait before the next cadre course is given. Certainly being corporals and getting some practice handling men will be better than standing around.

The sergeant, after a lot of comical wandering about, read us part of his report on us to Capt. Baring today. He said we "arrived late but worked hard to catch up to the rest of the squad, and have succeeded in passing many of the other men. The drill has been difficult for them, as they lack snap and tend to walk carelessly—perhaps an American habit? (That's exact quote.) They have caught on quickly, worked well with the other members of the squad, and have very strong senses of humor." "Good, huh?" he asked when he finished.

He got hold of my diary the other day, thumbed through till he found a compliment to himself, and has been pestering me ever since: "Bolte, where's my diary?" Today he sent a lad over to get it, and I replied that I'd let him have a copy of the first edition after the war. This morning he's been telling us not to buy our way into commissions, as the last OCTU squad did by giving the sergeants presents and liquor; Holmes said to go ahead on our own and not be slack. So when he asked again about the diary, I said "I'd consider that a bribe, Sergeant"—He said, "I shall take a very poor view of that, Bol-te," but he was baffled.

We were on the range-rifle Monday, Bren gun Tuesday, Brister who couldn't hit his hat a week ago won a green hat for high company score in rifle and combined —typical example of the proof beneath his belief that he can do anything he sets his mind to. Just so he forced the dice to win for him on the boat after losing fifty or sixty bucks. He's comically slow at drill and Bren gun time-trials, but once he starts to move he's irresistible. Shooting slow, rapid and snap, at 100, 200 and 300 yards, with a strange and powerful 303 he got 130 x 165. Not great, I thought, but Holmes says it's the best recruit score he recalls. I had 113, which infuriated me; Cutting 114, Durkee 112. 110 is marksman. We helped our squad win the shoot, anyway; and we won the Bren course too. What a lovely weapon, accurate, smooth, no recoil. We shot 5 singles and four bursts into a four foot target at 200 yds. I had 43 x 50, which was fair enough. The shooting was all day Monday and half-day Tuesday, so we had a nice lay-off from drill and plenty of sleeping and soccer (football they call it, but we know better) between rounds.

We're in the rhythm. Our barracks is filled with new conscripts and new, still dewy candidates. We qualify as old soldiers, are sought out for advice, and feel confident.

Do have people write, and tell me things like what they eat and how the trees look. When this war's done I'm coming home and live in America forever, eat chocolate and jam and honey, smoke Camels, read the new books and tell tall stories about the gay old days in the King's Royal Rifles.

Much love to you,

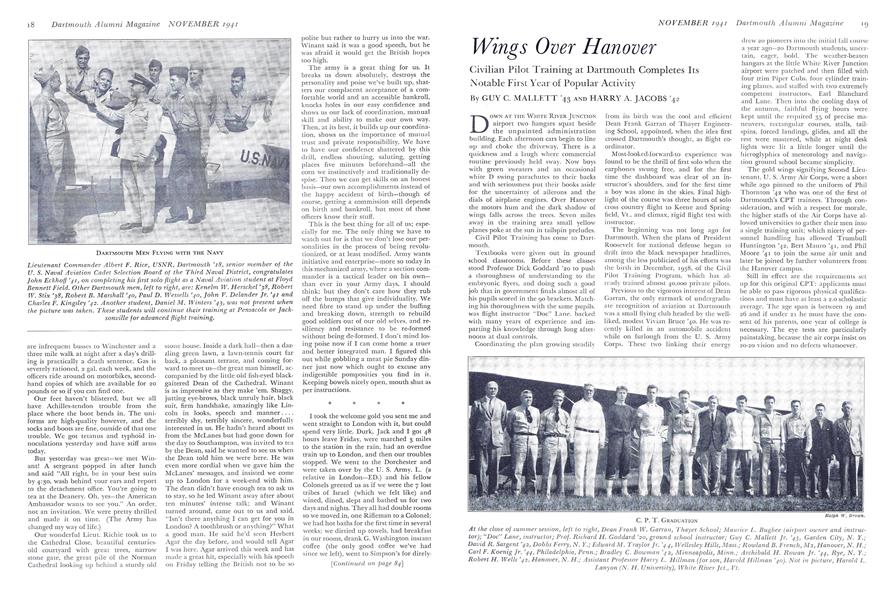

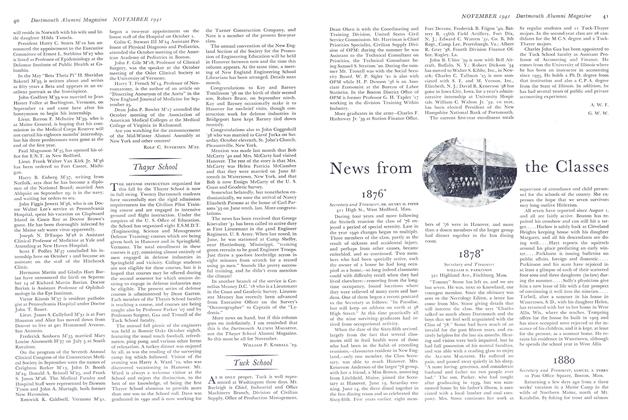

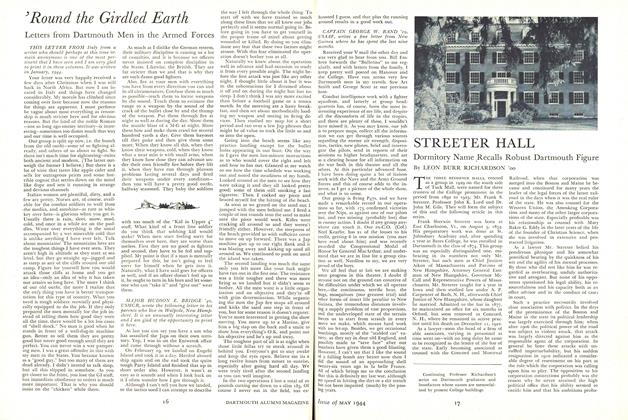

DARTMOUTH MEN FLYING WITH THE NAVY Lieutenant Commander Albert F. Rice, USNR, Dartmouth '18, senior member of theU. S. Naval Aviation Cadet Selection Board of the Third Naval District, congratulatesJohn Eckhoff '41, on completing his first solo flight as a Naval Aviation student at FloydBennett Field. Other Dartmouth men, left to right, are: Kenelm W. Herschel '38, RobertW. Stix '38, Robert B. Marshall '40, Paul D. Wessells '40, John V. Delander Jr. '41 andCharles F. Kingsley '42. Another student, Daniel M. Winters '43, was not present whenthe picture was taken. These students will continue their training at Pensacola or Jacksonville for advanced flight training.

Charles G. Bolte '4l, undergraduate editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE last year, John F. Brister '4l, andWilliam P. Durkee 111 '4l, enlistedin the 60th regiment of the King'sRoyal Rifles in England this summer.A limited number of Americans aretraining for officers' commissions inthis historic and noted regiment ofBritish infantry. Bolte has thusbacked up convictions expressed inhis widely published letter to President Roosevelt last spring, urgingimmediate entrance of the UnitedStates into the war. This position wasendorsed by the editors of The Dartmouth. Abstracts from RiflemanBolte's letters home are published below by courtesy of his father, GuyW. Bolte of Greenwich, Conn.—ED.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDistinctive Student Achievement

November 1941 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

November 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

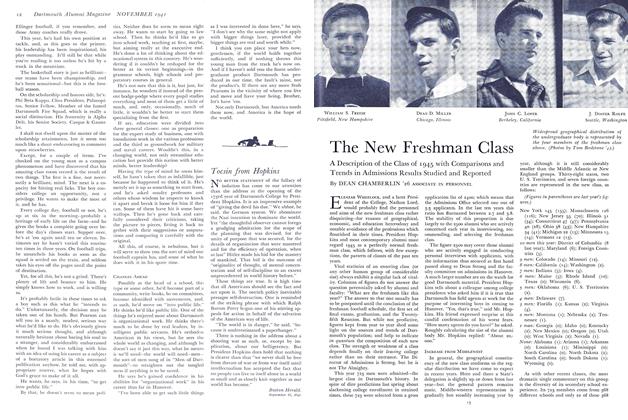

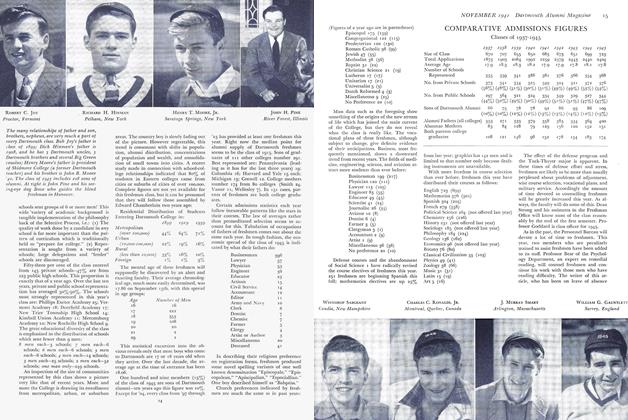

ArticleThe New Freshman Class

November 1941 By DEAN CHAMBERLIN '26 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1941 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938*

November 1941 By CARL F. VONPECHMANN, J. CLARKE MATTIMORE, DAVID J. BRADLEY -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in New York

November 1941

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

APRIL 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDartmouth Sea Dogs

March 1940 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWinter and Rough Weather

DECEMBER 1983 By Doug Greenwood