In his recently published autobiography entitled "My Life and Times" (Harper Brothers) Jerome K. Jerome has some entertaining passages on his experiences as a skiier in the chapter on "The Author at Play."

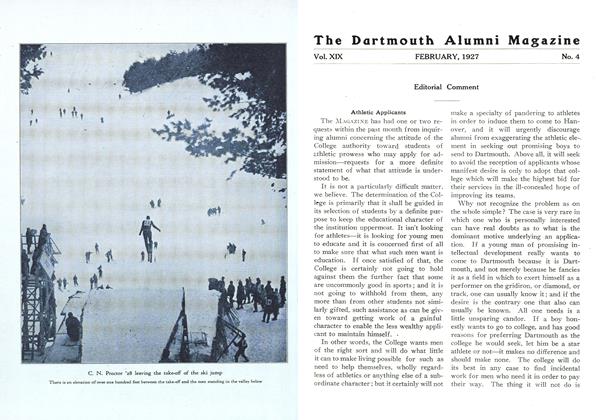

Some of his experiences on skis in Switzerland will be interesting to readers of the Magazine who have themselves tried to master the art of skiing. To quote: "Doyle was great on winter sports; and was one of the first to introduce skiing into Switzerland. Before that, it had been confined to Norway. All Davos used to turn out to watch Doyle and a few others practising. The beginner on skis is always popular. My own experience has convinced me that it is, practically speaking, impossible to break your neck, skiing. There may be a way of doing it; if so, it is the one way I haven't tried. I must have been forty-five when I first put on skis. I had the advantage of being a good skater, and knowing all that could be done with the old-fashioned snowshoe. Eventually I became fairly proficient. But were I to have my time over again, I would not leave it quite so late. Back somersaults, and the splits are exercises less painfully acquired in youth.

"Arosa is an excellent centre for skiing. I had had some fine runs and was in good form. I hired a boy from the village to come with me: and climbed the slopes of the Weibhorn. No experienced skier ever goes out alone. There are positions, quite easy to fall into, from which it is anatomically impossible to rise without assistance. The snow was just perfect that day. There had been a slight fall in the night, and the surface had not yet frozen. We climbed for two hours; and then on a narrow plateau we stripped the skins from our skis and fastened them, round our waists, tightened our straps, and launched forth. Often have I envied the swallows, watching them sweep on poised wing downward through the air till they almost touch the ground. I envy them more now that I know what it feels like. I can imagine only one more wonderful sensation, and that is the "jump"—an ugly word that does not really describe it. The signal is given to go, and the skier gently moves forward, skis straight, side by side, with the knees just bent. The hard, beaten track grows steeper. The pine trees glide past him, swifter and swifter. Suddenly the trees divide: the track heads straight as an arrow to—nothing. And then that glorious leap into sheer space with arms outstretched and head thrown back. I wonder how long it seems to him until the earth comes rushing up to meet him, and he is flying through the cheering crowd towards the flagstaff. It only wants nerve.

"One of the most dangerous things that can happen when skiing is to strike a sunk-fence. A broken ankle is generally the result of that; and once I came upon a man, sitting on the edge of a precipice, over which his skis were projecting. He dared not move. He had plunged his arms into the snow behind him and was hoping it would not give way. But haying regard to all the dangers that a skier is bound to face, the marvel is that so few accidents occur: and even were they umpteen times as frequent, I should still advise the average youngster to chance it.

"The thing to beware of is exhaustion. Skiing, like riding, requires its own particular set of new muscles. Until these have been built up, avoid long excursions. It was at Villars I first put on skis. One, Canon Savage, got up a skiing party and asked me to come in. I told him I was only a beginner, but he said that would be all right; they would look after me; and at eight o'clock the next morning we started. On the way home, I found it impossible to keep my legs. I would struggle up merely to go down again. Towards dusk, I fell into a drift, and lost my skis. The fastenings had become loosened. They slipped away from under me,« and I watched them sliding gracefully down the valley. They seemed to be getting on beter without me. I had taken an equal dislike to them and, at first, was glad to see them go. Until it occurred to me that with nothing on my feet but a pair of heavy boots, I had not much chance in my then state of exhaustion of extricating myself. I shouted with all the breath I had left. Maybe it wasn't much; and anyhow the Canon and his party were too far ahead to hear me. Fortunately a good Christian, named Arnold, thought of me and came back. I mentioned the incident to the Canon the next morning, but his sense of humour proved keener than mine. He found it amusing."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSARAH CONNELL GOES TO THE DARTMOUTH COMMENCEMENT OF 1809

February 1927 By Dr. James A. Spalding '66 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1927 -

Article

ArticleA POLISH UNIVERSITY TODAY

February 1927 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

February 1927