for the year 1925-26 Lektor in English at the University of Krakow

The old Commonwealth of Poland died in 1794. The University of Krakow, however, lived on. It served to bridge the gap between 1794 and 1918 perhaps more effectually than did any other Polish institution. It kept in continuity the stream of Polish intellectuality which had flowed through it without break since 1362. It preserved within its walls many of the traditions and written records of the intellectual and political life of the old government, and its halls were filled continually with students who came there to share its glorious traditions. The castles on the Wawel hill are empty today; the royal palaces have become government offices or public buildings; the University alone is the same that it has been in these five hundred years, the bright shining star in the intellectual life of Poland.

Fate has played many severe tricks upon the city in which the university dwells. In the Thirteenth Century it was taken by the Tartars and all but destroyed; in the Seventeenth Century it was captured and pillaged by the, Swedes, while Polish armies were striving to hold off German, Muscovite, and Tartar invaders. In the Eighteenth Century it was taken by the Russians* and later put under the domination of Austria. Its population which had once been 500,000 at the height of its greatest glory fell to about 10,000 after the days of Kosciuszko, but a steady growth in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries has brought its population up to 200,000 or thereabouts.

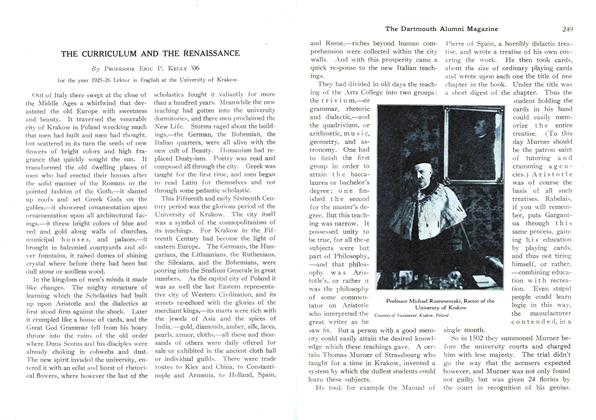

As a university city it has a cultural atmosphere almost without equal in Europe. For Krakow is a pure Gothic City untouched by the "beautifying" and "improving" influences of the Nineteenth Century. It has been said truly that the whole city might be put under a glass case as a museum exhibit. Here is the traditional center of all Polish culture. The Polish Kings built their castles and churches and were crowned here in early days, here the merchant princes and "schlacta" built their palaces, here the Romanesque remnants of Poland are to be found, here are the adornments and beauties of the Renaissance, here are four well-stocked museums, and three large libraries. And here is the university which has played a leading part in the history of Polish culture. The old library building is a positive gem, the present generation has outgrown it, huge as it is, and uses for a reading room an adjoining building across an Italian bridge.

The functions of the University are many. One of them is of course the training of professional men and women, but the chief function is the implanting of culture through the teaching of the liberal arts. The students are of all ages, from 16 to 60, and one old man who attends many of the lectures seems to be above that age. The war has been responsible for the fact that students of advanced years are still undergraduates, for the period 1914 to 1920 in this part of the world chopped many useful years out of the lives of men and women. As Poland is to be probably the most powerful Slav nation in the future this cultural training will be particularly valuable. In the olden days when Poland was really the leader of the Slavs, the University played a great part in the settlement of international questions, and it seems as if the future might bring a like state of affairs since the old empire known as "Russia" has disappeared and the Slav tribes held together by force in the past hundred and fifty years have broken away from that centralized control. The really intellectual forces in the Moscow government seem to be in exile; a new government may arise there in time, but it will be a much smaller power than formerly and may establish itself only after many years. It seems probable that the leadership in Eastern Europe will return to Poland, and for the acceptance of such leadership her sons and daughters need just such education as the University of Krakow gives.

Through all periods of national vicissitudes the university has been a more or less constant quantity. Its teachings have changed with the years and times, but it exists today as the same intellectual leaven that it was in the days when Poland was driven constantly to defence by attacks from all sides. It was a shining light in the period of Scholasticism, it took up the New Learning in the period of the Renaissance after its walls had resounded with the healthy discussion of the old and the new. Its faculty and students had a national and political value as well as an intellectual value, and participation in national politics has continued until the present day. It played a part in all the cultural and religious movements of the 16th and 17th Centuries and blossomed into a Golden Age in the same years that England flowered into the Elizabethan Period. The reaction brought in bad Latin, classical precepts, Macaronic verse and prose. Reform again drove out Latin in favor of the vernacular in the late Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Century.

The Romantic Period came with a burst of glory into Poland. Byron was greatly influential in it, although translations of Scott and a new interest in Shakespeare went with the movement. Romanticism was more than a term in Poland. Romanticism meant the triumph of the dream and inward longing over reality, and in a nation which had ceased to exist on the surface, Romanticism was a call to arms. The Revolution of 1830 was a distinctly Romantic Revolution. Efforts of foreign governments to stifle the Polish speech and literature only caused the coals of patriotism to burn more brightly beneath the surface of oppression. Boleslawski, a writer whose comment was requoted in 1916, said:

"The opposition between inward feeling and outward conditions, between the burning faith of the heart and the crushing tyranny of the commonplace day has reached with us a state of tragic tension, upsetting the balance of delicate natures."

The universities in Russian and German Poland were more harshly censored than was Krakow, and despite the fact that Poland was despoiled* of large quantities of her books and manuscripts in order to benefit Moscow, the university clung to her possessions zealously and managed to save them. Efforts at "PanSlavism" and "Mittel-Europe" were unavailing in intellectual Poland because the men of intelligence could detect the selfish motives behind each of these movements. When the New Poland arose it was the university in Krakow which had ready a supply of teachers, students, and men of affairs to send to the other portions of the republic.

The University of Krakow has today 5,706 students, of which 1,431 are women. Of the total number of students, 1,655 profess the Hebrew faith, the students of this faith coming mostly from the old Jewish city of Kasimierz now the Ghetto of Krakow. This city was set off in the 14th Century by King Kasimir the Great as a dwelling place and refuge for the Jews who were being persecuted in many other parts of the world. Refugees from the old Russia came there in large numbers after the persecutions in the lands outside the Pale. In the advanced seminar in which I had a set of lectures on American Literature, the Jewish students form about half the class. This is also true of the pro-seminar in which I had a class of beginners.

The pro-seminar, by the way is simply the elementary class in any subject. Most students go two years to pro-seminars, and two years to seminars in the university training. The two years of proseminars, correspond to the last two years of an American college. The two seminar years are periods of research or advanced work. My pro-seminars were in the classes of Professor Dziewicki, a lovable old teacher, now more than seventy, who has spent forty years in teaching Polish youth. He is a great admirer of Byron and in University of London days translated Conrad Wellenrod in Byronic metre and spirit. He has compiled an English-Polish dictionary, translated many books, among them the four volumes of Reymont's Peasants, and at present is engaged by an American publisher to translate Reymont's Promised Land.

My greatest trouble in this pro-seminar was lack of books. The Tauchnitz editions had taken such a rise in price that the students couldn't afford them. I did find however some small Austrian prints of stories from the Arabian Nights, the Iliad, Canterbury Tales, Cooper's Prairie, Robinson Crusoe. The students buy but few books. They find what they want in some of the libraries in the town, the College Bibliotek, the seminarium Bibliotek,the libraries in each of the clubs or Kolo's,or they borrow from the Lektor or Professor who is constantly building up his library for the benefit of others. The University Bibliotek now has close to 500,000 books, and a great quantity of valuable manuscripts and old prints. Modern American books are rather scarce however, due probably to the prohibitive exchange in money rates prevalent just after the war. Now that the Polish Zloty has been stabilized it should be possible to have more books from America.

More is done each year for the comfort of the students, the majority of whom are not rich or even moderately comfortable. In cases where there has been actual suffering, such as came during the occupancy of an empty barrack by poor students, the college itself, and an association of students have given assistance. The student in the Liberal Arts department pays normally at the maximum 100 zloties a year for tuition. If he has no money, he can defer part of this payment for 10 years. In the professional schools the fees are a little larger. This means that at the normal rate of exchange the university fee for a Polish student is less than $25 a year. The Students' Aid Society is an association of mutual help to which each student pays 10 zloties at the beginning of each year, and from this fund money is drawn as a loan by needy students. Students working their way through the University live in one of the two university dormitories at a very low rental rate,—perhaps eight zloties or $1.25 a month;—the dormitory on Jablonowski street holds about 350 men. Meals may be bought in the university student kitchens for about 60 groschen or eight cents. In this same building are found club rooms, a library, a recreation room, and trade rooms,—that is to say a shoemaker's room, a tailor's room, a stationer's room, in which students sell the goods usually handled by men of such trades.

The women are not so fortunate in dormitories, but the need has been partly met by the convents of the town which have thrown open their doors to women students in the university. Here at a very moderate cost live a large proportion of the Christian women. There is a women's '"dormitory," however, operated by a number of students themselves; it occupies as yet only two floors of a city building. There are many pensions in the city and many boarding places. There are six "kitchens" this winter where a student may eat at 50 groschen a meal.

The Krakow student on coming to the university is put "upon his own" almost immediately. He registers, gets his catatogue, attends his first classes and has his "book" signed by each professor, and then he may do just as he pleases. He may attend classes or he may stay away. The one examination which he must pass at the end of the year is held up to him at the very, beginning as a very stiff test, and he studies hard in preparation for it during the year. Classes are always full, although no roll is ever taken or called. In fact classes are so full that one must literally fight his way in if he comes the least bit late. The whole burden of achievement is placed entirely on the student. He is made to see at the very beginning that it is entirely his business whether or not he passes or fails. He should come to the university at the age of 18 if he has entered lower schools at the required age and gone through all classes of the gymnasium without failure.

By the time that a student reaches the seminar he should be able to read in two or three languages, so that he can bring to the class room information from different points of view. Books in foreign languages will be assigned to him just as casually as in American schools one assigns books in the mother tongue. He must make a thorough report on one subject during the year in order to be certified for the examination, and he may take three months or the whole year in which to prepare his paper. I speak of course of the only seminars of which I have any knowledge. In the language seminars he must make his reports in the language in which the seminar is conducted. The papers that I have heard have been thorough treatises on subjects about which there is available literary criticism. Byron is still the greatest English favorite generally I think, in Poland, although Dickens and Shakespeare are much read. I found that most of the students in the English seminar know of Poe and Upton Sinclair, they have read Whitman, Jack London, and Longfellow, and are much interested in the present school of American writers.

Social life is rather a new phase of University life in Europe. Athletics have not yet come to play such a large part as they do in American Universities and Colleges. The student organizations known as organized for the most part in order to enable the members to do better work in the university. Rooms are taken and furnished; a library is kept up; lecturers are asked to come and speak sometimes; teas and dances are given occasionally; there is much studying and work in common. These kolo's are elective in membership and choose members from different departments. There is the History Kolo, the Philosophy Kolo, etc. Then there are Kolo's according to race, the Czech Kolo, the Hungarian Kolo, etc. There are Kolo's made up of dwellers in different cities in Poland, the Warsaw Kolo, the Lodz Kolo, etc. In most of the public social events of the city, academicians are admitted at half-price. The members of the different departments in the college wear different colored caps, thus blue stands for philosophy, red for medicine, and green for law.

College observances are for the most part traditional. At the beginning of the year the Rector who holds office for one year only receives the insignia of office from his predecessor. The procession is quite Medieval, the masters of arts in robes carry scepters, and two attendants stand guarding the rector's throne. A procession is made each year to the court of the ancient Library where there is. a shrine to St. Jan Ivanty, a famous teacher and writer of the Fifteenth Century. The religious ceremonies take place in St. Anne's Church which has stood since the Fifteenth Century in the street of that name. In the large ha'l where the public observances are held, are paintings of former rectors of the college, bishops and Cardinals, and the Kings and Queens of Poland. A famous painting by Matejko, the great historical painter of Poland, hangs above the rector's throne. It shows Copernicus on his balcony in the city of Torun studying the skies. Another painting ing by Matejko in the rear of the hall shows the interior of the college court in the Fifteenth Century, it is called the Coming of Humanism. It shows the ambassadors from Prague pleading the cause of the Hussite Jerome of Prague.

What in detail do the students study? The titles of courses in the University catalogue resemble the titles listed in the catalogue of any American College or University, and are grouped under the heads of departments in one of which the students must "major." Although only one examination is given each year, the examination covers more than the "major" subject. The professor of the course usually determines beforehand whether or not the specified applicant shall be admitted to the examination. If the examination is in English for example there will be at the oral examination besides the English examiner, examiners from other departments who will also ask questions. The student must know something of Polish literature and history, something of German and French or Latin and Greek, something of Philology. Professor Roman Dyboski of the English department for example stands for just the broad culture that the university is supposed to give in its liberal arts department. He has written, in English, two authoritative books on Polish History and Life, he has translated a history of the city of Krakow, he is the author, also in English, of a philological treatise on Old English; he has written in German and French, and is the author of many Polish books, one of them being the account of his experiences in Russia where he was held a captive by the Bolsheviks from 1916 to 1923. He has been incidentally a lecturer at the University of London, and Geneva, and is the founder of an institute of Political Economy in the University. He is called upon by journalists frequently to comment upon affairs of state.

The Polish people are today beginning a new epoch, not only in their own history, but in the history of mankind. In the past they were perhaps too liberal in an age of centralized governments; and the records of many liberal movements lie stored up in Slav countries waiting only the magic touch of the scholar to release them for the world. We know now but very little of a history that in its way seems just as important to civilization as does the civilization of Western Europe. There are thousands of manuscripts to be read, thousands of investigations to be made, thousands of books to be written, out of which a few will be lasting and will contain the essence of the culture which the Slav has to offer to the world.

The roof of a university dormitory, with the town hall and university buildings in the background Courtesy of Swiatovvid, Krakow, Poland

A demonstration to raise money for poor students Courtesy of Swiatowid, Krakow, Poland

Novum Collegium, the College of Liberal Arts of Krakow University

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSARAH CONNELL GOES TO THE DARTMOUTH COMMENCEMENT OF 1809

February 1927 By Dr. James A. Spalding '66 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

February 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

February 1927 By Herrick Brown

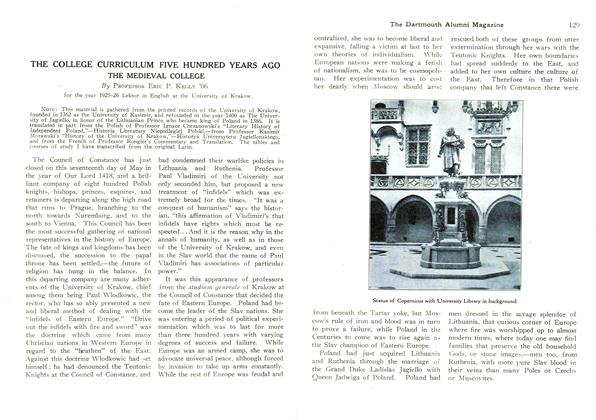

Professor Eric P. Kelly '06

Article

-

Article

ArticleCHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION

May, 1914 -

Article

ArticleFEW BRAIN FARMERS MET

April1935 -

Article

ArticleClub Calendar

January 1952 -

Article

ArticleHOCKEY

JANUARY 1964 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE OUTING CLUB

February 1936 By H. T. A. Richmond '38 -

Article

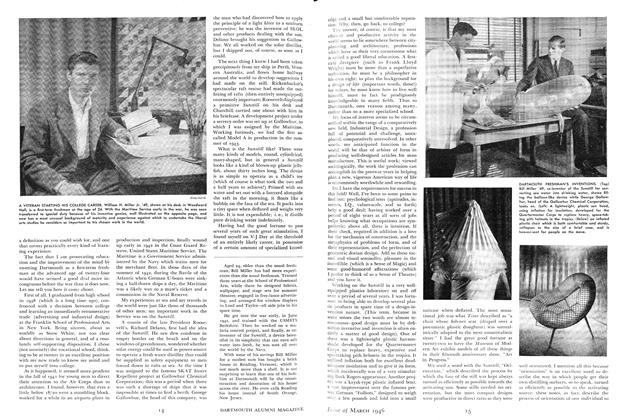

ArticleA Very Wise Man Once Gave Me a Gloomy Warning

March 1946 By WILLIAM H. MILLER JR. '49