POPULAR DARTMOUTH PROFESSOR SUCCUMBS TO PNEUMONIA

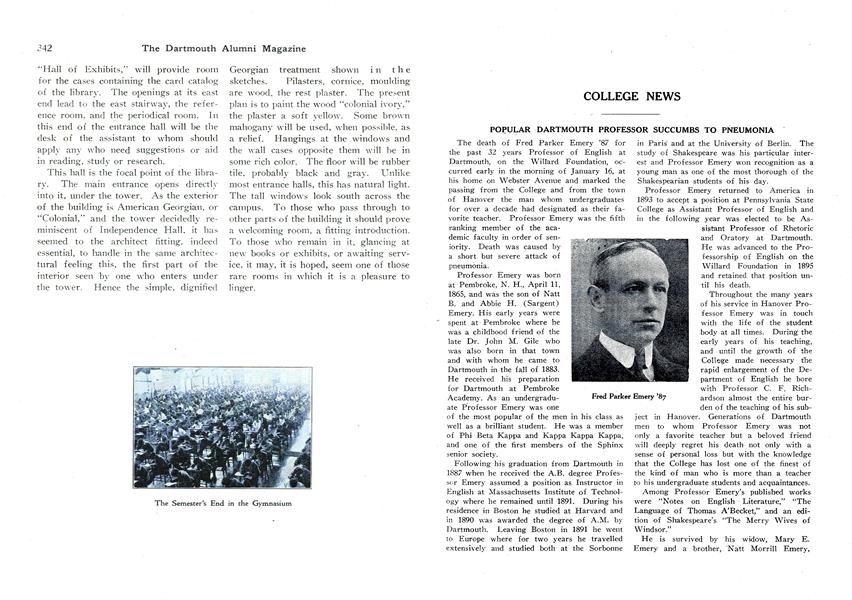

The death of Fred Parker Emery '87 for the past 32 years Professor of English at Dartmouth, on the Willard Foundation, occurred early in the morning" of January 16, at his home on Webster Avenue and marked the passing from the College and from the town of Hanover the man whom undergraduates for over a decade had designated as their favorite teacher. Professor Emery was the fifth ranking member of the academic faculty in order of seniority. Death was caused by a short but severe attack of pneumonia.

Professor Emery was born at Pembroke, N. H., April 11, 1865, and was the son of Natt B. and Abbie H. (Sargent) Emery. His early years were spent at Pembroke where he was a childhood friend of the late Dr. John M. Gile who was also born in that town and with whom he came to Dartmouth in the fall of 1883. He received his preparation for Dartmouth at Pembroke Academy. As an undergraduate Professor Emery was one of the most popular of the men in his class as well as a brilliant student. He was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Kappa Kappa Kappa, and one of the first members of the Sphinx senior society.

Following his graduation from Dartmouth in 1887 when he received the A.B. degree Professor Emery assumed a position as Instructor in English at Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he remained until 1891. During his residence in Boston he studied at Harvard and in 1890 was awarded the degree of A.M. by Dartmouth. Leaving Boston in 1891 he went to Europe where for two years he travelled extensively and studied both at the Sorbonne in Paris' and at the University of Berlin. The study of Shakespeare was his particular interest and Professor Emery won recognition as a young man as one of the most thorough of the Shakespearian students of his day.

Professor Emery returned to America in 1893 to accept a position at Pennsylvania State College as Assistant Professor of English and in the following year was elected to be Assistant Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Dartmouth. He was advanced to the Professorship of English on the Willard Foundation in 1895 and retained that position until his death.

Throughout the many years of his service in Hanover Professor Emery was in touch with the life of the student body at all times. During the early years of his teaching, and until the growth of the College made necessary the rapid enlargement of the Department of English he bore with Professor C. F. Richardson almost the entire burden of the teaching of his subject in Hanover. Generations of Dartmouth men to whom Professor Emery was not only a favorite teacher but a beloved friend will deeply regret his death not only with a sense of personal loss but with the knowledge that the College has lost one of the finest of the kind of man who is more than a teacher to his undergraduate students and acquaintances.

Among Professor Emery's published works were "Notes on English Literature," "The Language of Thomas A'Becket," and an edition of Shakespeare's "The Merry Wives of Windsor."

He is survived by his widow, Mary E. Emery and a brother, "Natt Morrill Emery, vice-president and comptroller of Lehigh University.

The following appreciation of Professor Emery, written by his colleague, Professor E. B. Watson, also of the Department of English, was read at a meeting of the Ticknor Club of which Professor Emery was a charter member.

"Today, with unusual beauty of circumstance, has passed from our number one of the most universally beloved and most significant personalities—that of a teacher of English letters, whose service has been almost exactly coincident with the great Dartmouth awakening. His relation to the College tradition was even more complete. A son of New Hampshire, he was trained in a New Hampshire school and was graduated from Dartmouth in the class of 1887. Although he had spent six years intervening before his appointment to the Dartmouth faculty teaching and studying in Boston, Paris, Berlin, and elsewhere, neither his technique nor his inspiration appear to have come to him chiefly from such opportunities. At all times he gratefully and affectionately acknowledged such indebtedness to Prof. Charles F. Richardson, "of saintly memory", as he liked to say, the great teacher of his student days.

"In what chanced to be our last long talk together he recalled memories of this teacher that we shared in common with many generations of Dartmouth men, and once more spoke of him as his ideal in the art of teaching for he was one who compelled not by force but by love and genuine brilliancy of mind. Professor Emery modestly added that he still labored in the hope of attaining to this ideal.

"When the Dartmouth editor expressed Professor Emery's meaning to the present college generation as "a man who was in the finest sense of the phrase a gentleman and a scholar," his words had for me more than their commonplace surface meaning, for they happen to have been those chosen by Professor Emery himself to epitomize his idolized exemplar.

"In no sense was Professor Emery's work at Dartmouth ever the result of revolutionary impulses or youthful enthusiasms for the reflected fads and fancies of a passing day. He was always content to teach as he had been taught and to derive inspiration from first-hand contacts with what he had known to be good. He was in more than one sense the outstanding witness before us of that truth with which Bishop Dallas unforgettably linked his memory, that he who has known beauty and loved it and taught others in turn to impart it to more disciples has, indeed, lived again and again.

"I came into Professor Emery's classes in the fall of 1898, four years after his appointment at Dartmouth. He with Professors Richardson and Laycock constituted, as I recall, the entire English department. With him I studied rhetoric and composition, the history of English and American literature, and the plays of Shakespeare. Although in the plodding ways of graduate study I have since traced and retraced the paths then opened to me, I have often been astonished to recall the comprehensiveness of Professor Emery's presentation of these subjects. He had that rare faculty, especially among students of literature, of seeing the whole as well as the detail. He charted with almost infallible proportion and precision, while also giving an impression of thoroughness that was almost uncanny. Since my recent return to Dartmouth I have several times heard him expound literary subjects with much the same technique. I am still baffled to explain his peculiar power of exposition.

"Two personal gifts, more than any others, characterized his genius for it was little else his faculty of an almost faultless memory and his skill in the perfect phrase. I recall no error of his memory, as such, in all I have heard him say. Almost as truly I may say that I have never heard from him a carelessly turned or unfinished phrase.

"These gifts he displayed, brilliantly in conversation. In the few minutes of friendly chatting at our desks each day he delighted to carve, the finely lined phrase and at the same time to recall with precision the name and record of some student of the class of 1903 or of one a decade earlier. Perhaps he would recall the exact days that were coldest during the last ten years or toss off the dates of the three quarto editions of Henry V.

"There was neither display nor effort in this simple play of a full mind. He never seemed to hesitate for a name or date or to fail in fixing a fit and graceful phrase to a fleeting thought.

"This instinct for the finished phrase will perhaps be my most lasting impression of his mental greatness. It was far more than the faculty of easy speech, although it was this also. His was a finely cultivated sense of word values and phrase efficiency—a modern Euphuism without any of the excesses associated with that much abused term. Not only was he expert in phrase making, but his critical faculty led him to sense infallibly phrase value and to delight in it, whether it was found in Chaucer, Shakespeare, the Bible, Marlowe, Milton, Keats, or in the conversation of a friend. How many citations that recur to me I can recall as those to which Professor Emery first directed my attention as I was feeling my way from the old Boston Latinism to a freer choice of beauty.

"An instinct for beauty was his guiding impulse, but a sense of humor was hardly less so. When in class one day a student begged him to intervene on our behalf with the Dean Professor Emerson known affectionately to all as Chuck—Professor Emery with a flash both of wit and humor replied: "Shakespeare has written a better prayer than I could for your present needs, 'Use lenity, sweet Chuck.'" This became a universal petition of my student days. To the credit of our kindly Dean it should be said, it rarely failed of response.

"It is not a meaningless coincidence that in the same college year death should take from us Dr. Tucker and Professor Emery. Both were of the Dartmouth fellowship in the best sense of that term; both were tradition bearers of the best that has made this American college; both were recreators of Dartmouth on the new foundations of realist thought; both were loyal to an ideal of spiritual beauty above and beyond this and every college and this and every age; both were inspired with an unshakable faith in the simple work of the teacher and scholar as the most beneficient and satisfying of life's employment; both were endowed with gifts of gentleness and efficiency that would have brought them followings anywhere and which could have won for them wide fame outside the academic circle; both were content, however, to give their best, almost their only endeavor, for that single and to them sufficient object of devotion, this academic fellowship, regardless of any other personal sonal considerations whatsoever. Both in the highest sense were loyal spirits not to this or any college as such but to the purpose for which this and every college must always stand the promotion of the beauty of life.

"No one could long associate with Professor Emery without realizing this orientation of his thought. He had come under the spell of a great teacher of beauty; he had known the great exemplars of beauty in literature at first hand. Like Goethe he preferred to return to these standards of excellence rather than lend himself with enthusiasm to the hosts of new and, as he believed, lesser claimants. Just as Goethe in the Italienische Reise complained of having to look in the galleries at a Menge of good but lesser works of art before coming upon the great, so Professor Emery, although he showed an astonishing familiarity with the Menge of literature new and old, went back instinctively and always to the great masters of beauty and diction.

"His philosophy of beauty, expressed in class, in his life as a kindly gentleman, in the adornments of his home, we may borrow from those words graven in Stone by St. Gaudens to mark the grave of Whistler:

"The story of the beautiful is already complete, hewn in the marbles of the Parthenon and broidered with the birds upon the fan of Hokusai."

Professor Emery's death occurred after the editorial section of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE had been set in type. An editorial appreciation of Professor Emery will be included in the next issue of the MAGAZINE.

Fred Parker Emery 'B7

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSARAH CONNELL GOES TO THE DARTMOUTH COMMENCEMENT OF 1809

February 1927 By Dr. James A. Spalding '66 -

Lettter from the Editor

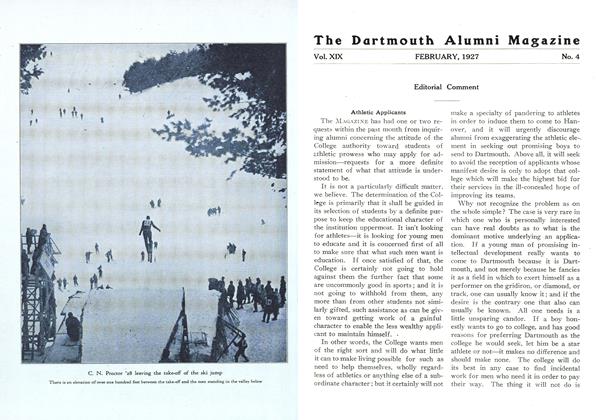

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1927 -

Article

ArticleA POLISH UNIVERSITY TODAY

February 1927 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

February 1927 By Herrick Brown