(Of The New York Sun)

President Ernest M. Hopkins of Dartmouth has arrived at the conclusion that the tail is wagging the dog, that intercollegiate football has assumed an importance in the minds of both the undergraduate and the man in the street which overshadows the educational function of the American university. There is nothing particularly original in President Hopkins' conclusion, but, unlike his contemporaries, Hopkins proposes to do something about it. Instead of wringing his hands and deploring the exaggerated interest in football Dartmouth's president offers a constructive program of reform. A warm friend of football, he would perpetuate the character building features of the game while toning down its objectionable phases.

Whether or not one agrees with Dr. Hopkins—and few of football's adherents either inside the colleges or out will accept his radical suggestions—one cannot deny that he has evolved a plan calculated to make football more of a sporting proposition and less of a grim cousin to organized warfare. There isn't much fun in football as played today for any one but the spectator. We have turned our backs squarely on the English public school creed— sport for sport's sake. American football is a grim business in which a terrible premium has been placed on victory. Financially football has become an institution comparable to the motion picture and the automobile industries. High- salaried executives must be employed to handle the vast amount of capital embraced in colossal stadiums, transcontinental trips, $150,000 gates, autumn training camps, elaborate scouting forces and so forth.

An up-to-date graduate manager must have the talents of a corporation director. Besides handling vast sums of money he is responsible for digging up "desirable material," arranging scholarships for "deserving athletes," signing up expensive coaches on long term contracts and dealing diplomatically with rival colleges which demand certain percentages of the receipts. Football is big business with a vengeance. The printing contracts on tickets runs into large sums. The overhead and depreciation on plants are abnormally high. An empty stadium is a losing investment. The graduate manager must provide attractions to fill his stadium three or four times a season. Only a winning team will draw the crowd in games lacking the flavor of traditional rivalry. Hence the demand for colorful opponents.

A winning team means a competent coach. But the coach must have star players. Stars cost money—indirectly. Often they must be tempted by "attractive propositions," such as managerships of laundries, eating clubs and so forth. Most colleges keep elaborate card indexes, tabulating every potential high school grid star. These kids are systematically followed up by scouts. The bidding for a desirable man waxes merry. Yes, college football has become a highly organized business.

Once on the field the boys are mere puppets. High-salaried coaches pull the strings. Campaigns are conducted with a grim intensity, which eliminates to a large degree any recreational flavor. Football builds character the same way military training does, by instilling discipline, unprotesting obedience to authority. The factor of amusement—for the player—is subordinated to the necessity of winning. But it is marvelous fun for the spectator.

The writer agrees with President Hopkins that the elimination of the professional coach would be a Utopian step forward toward the ideal of sport for sport's sake. The Sun has repeatedly stressed the advisability of giving the college game back to the college boy. As played today, football has become a co'ntest between coaches. "Capablanca Zuppke" maneuvers his human pawns against "Alekhine Yost." It is largely a coach's game instead of a sporting match between students. It seems to us that the boys should be left to their own devices on the field; that they should work out their own salvation unaided by expert advice.

Coaching should be confined to men who had graduated from their respective colleges the previous year. No man out of college two years should be eligible to coach nor should any institution be permitted to go outside its own graduate body for a teacher. That would be real amateur sport. College boys would evolve their strategic plans all by themselves. It actually would be Yale versus Harvard—not Horween versus Tad Jones. This would put a premium on student originality. Amateur Napoleons would get a chance to confound amateur Wellingtons. We should have technically poorer football, undoubtedly, but it would be more amusing and more genuinely representative of the competing institutions.

We can't agree, however, that seniors should be automatically barred. They have as much right to play as sophomores or juniors, and by senior year their classroom work is usually so well organized that they have more leisure for sports. To bar seniors from competitive, athletics would be a travesty on justice. Some men don't develop their potentialities as players until their final year. Football is a complex game. Two years is too short a time to develop maximum proficiency. Why should a senior be summarily sentenced to confine his recreational activities to auction bridge, a little serious drinking and tea fights? Why deprive the senior of zestful competition ? Even as it is, college sports cover too brief a span.

The two-team idea has certain merits, but what would prevent a coach concentrating all his strength on one team with the idea of making sure of a 50—50 split ? The thing might degenerate into a varsity game and a junior varsity match, with nobody giving a whoop who won the lesser contest, thus defeating President Hopkins' idea. How could you compel a coach to shuffle his stars evenly between his two teams? The temptation would be to put all the good men on one eleven and throw together the leftovers to form a lack-luster B outfit.

We suggest an amendment to President Hopkins' second proposal. Have two games on the respective home grounds of the rival colleges, but let the aggregate score of both contests decide who won the match. Then if a coach insisted on putting his stars on team A he would have to pay the penalty of a weak B team. Under this revised plan both games would have real significance. Suppose the Yale and Harvard varsities met at New Haven while the Blue and Crimson reserves were playing at Cambridge. If the Eli varsity won its game 6 to 0 and the Harvard seconds finished on the long end of a 15 to 5 tally the day's total score would be Harvard 15, Yale 11. Maybe the spectators wouldn't keep an eye glued on the scoreboard. Telegraph operators would work overtime.

President Hopkins has started something Can he finish it?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AND CHOATE IN COLLEGE

May 1927 By Herbert Darling Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1927 -

Article

ArticleMOOSILAUKE

May 1927 By Daniel P. Hatch, Jr. '28 -

Article

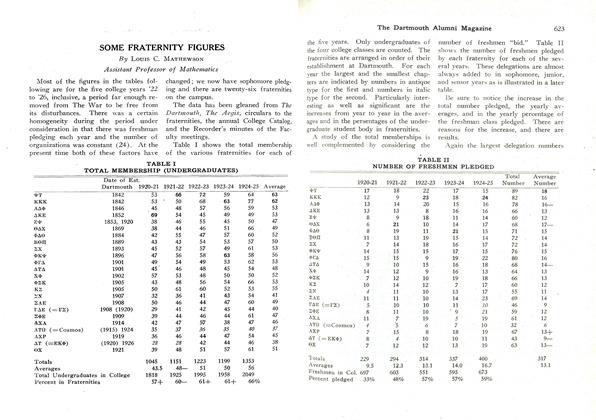

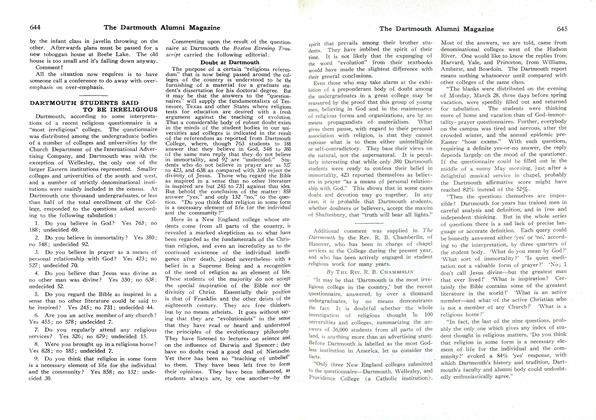

ArticleSOME FRATERNITY FIGURES

May 1927 By Louis C. Mathewson -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENTS SAID TO BE IRRELIGIOUS

May 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1927 By Herrick Brown