(From The Harvard Alumni Bulletin)

President Hopkins of Dartmouth offers a plan for the reform of football which calls for a limitation of varsity players to the sophomore and junior classes; for big games played on a reciprocal basis by a home team and a visiting team from each college on the same day; and for the restriction of coaching to seniors. On the face of it, the idea appeals strongly to everyone who feels that the football season has its faults. Yet it is not surprising that President Hopkins' proposals have not been everywhere favorably received. No college coach could be expected to battle to the death for a proposal that would wipe his tribe off the face of the earth. No sporting writer in the papers wants to see football news diminished to a quarter of its present volume, if he is paid space rates for his contributions. And by this time, the general male public, polishing up- their golf clubs, and fighting with their wives about summer plans, are beginning to tire of the discussion that has surrounded football since the close of the season nearly four months ago. Nevertheless, President Hopkins is highly esteemed among college graduates, and his recommendations will have weight. He is not a man given to idle talk. He does not take the attitude that football is wholly an evil; he loves the game; he talks of it as of a dear friend afflicted with elephantiasis.

His plan, however, carries implications which a casual consideration of it might not reveal. If all of his suggestions were adopted, the gate receipts of the football season would shrink very far below their present gargantuan proportions. The hundred or so men who are the special victims of football overemphasis in every college might be saved, but the hundreds who benefit from the money which the foot ball team attracts would suffer, unless we adopted the English university method of financing sports, along with the English theory of organizing them. The football gate receipts at Harvard last fall were considerably over half a million dollars. Before the current year is out, most of this sum will have been spent or allocated. It will support the crew, supply equipment to men who like organized exercise whether they have varsity ambitions or not, pay for the upkeep of the lawn tennis courts, and be directed into other useful channels. During the past winter more than 2,000 men at Harvard have taken part in athletic activities which were paid for by the Athletic Association, for the most part out of football receipts, and during the fall and spring the number of men who so profit is even larger.

The English universities run their sports practically without gate receipts. At Oxford and Cambridge every student is charged a considerable sum for the privilege of taking part in college sports and must pay that amount just as he must pay his tuition bill. He must supply his own equipment and frequently provide for incidental expenses as well.

The financial problem connected with the conduct of athletics in American colleges has grown into a serious one. We wish that it did not exist. It must be admitted that football is professionalized so far as one of its aims is to provide money for other purposes. Under those circumstances it can hardly be regarded as a strictly amateur enterprise. .But, as an eminent American once said, it is a condition and not a theory that confronts us. In what manner shall this condition be met?

The fact that other forms of sport now depend on football earnings should not stand in the way of substantial corrections in the game if they are greatly needed. That is to say, if the men who are competent to pass judgment on the situation as a whole are convinced that football has become, or soon will be, a real menace to education in the American college, gate receipts must not be permitted to block the path to better things. Doubtless other ways of obtaining money could be found in case of necessity. The fundamental questions are whether or not there is a real need for re form in intercollegiate football and whether President Hopkins has pointed out the way of bringing it about. Most people, we think, would answer "yes" to the former inquiry. As to the latter, we welcome President Hopkins' proposals. Whether or not they commend themselves to everybody, they are constructive; they will lead to reflection and discussion; and they carry a certain authority because they were put forth by one of the wisest, most progressive, and far-seeing college presidents of which this country can boast.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AND CHOATE IN COLLEGE

May 1927 By Herbert Darling Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1927 -

Article

ArticleMOOSILAUKE

May 1927 By Daniel P. Hatch, Jr. '28 -

Article

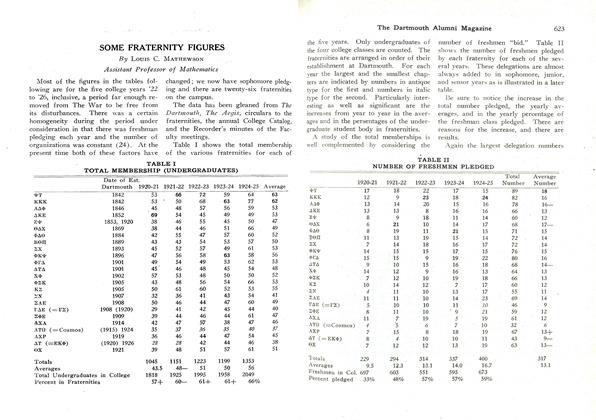

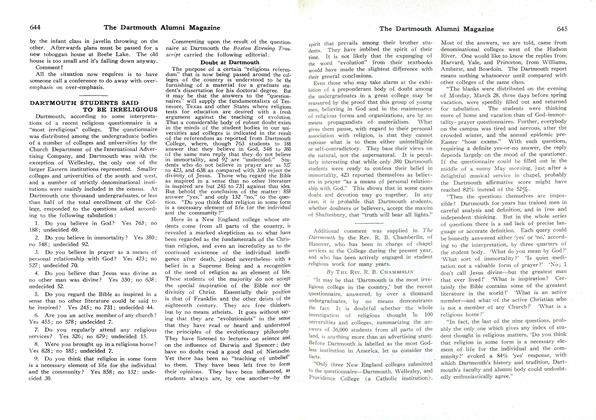

ArticleSOME FRATERNITY FIGURES

May 1927 By Louis C. Mathewson -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENTS SAID TO BE IRRELIGIOUS

May 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1927 By Herrick Brown

Article

-

Article

ArticleFIFTH ORDNANCE COURSE AT THE TUCK SCHOOL

February 1918 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

May 1951 -

Article

ArticlePay-As-You-Go Taxation

October 1942 By BEARDSLEY RUML '15 -

Article

ArticleWithin These Walls

May 1939 By Dwight Meader '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Moose on Ledyard Bridge

December 1973 By Robert Siegel -

Article

ArticleEpisode

MARCH 1932 By W. H. Ferry '32