The task of the Alumni Fund committee and the army of class agents working under its direction is to solicit with the utmost of effect and with the minimum of cost a great body of widely scattered men who are either graduates of Dartmouth, or non-graduates, who remain willing and anxious to assist according to their means in the advancement of efficiency on the part of the College which they reverence and love, and which they desire to enhance in power as an engine for the service of their country and their time.

This body of alumni and non-graduates numbers several thousand and it necessarily includes men of every sort of mental squint. In order to make appeal to it, the managers of the Fund devise every year a series of what are called "mailing pieces"—documentary appeals designed, to awaken interest on the part of those solicited—in such variety as hopefully to interest every kind of man. It follows that not every unit in the year's battery of mailing pieces will suit the fancy of every unit in the vast army which is being solicited. That couldn't be managed. Some of the appeals will suit some, and others will make a greater appeal to others. The important thing is to reach all, at some time or other, during the months in which this solicitation is being prosecuted.

The successive committees charged with this work—it is probably the most vitally important work which alumni are doing at this juncture for the welfare of Dartmouth—devote a vast amount of care to the "psychology" of their campaign literature. That means that the various items in their arsenal of appeals must be considered on the score of their likelihood of awakening interest in a variety of ways adapted to the varying mental attitudes of the men to be approached concerning this fund—not merely with a view to attracting, but also with a view to avoiding repulsions. One must reckon with the propensity of men to discover flaws, or to take dislikes where none are sought to be engendered, especially when it comes to a matter of contributions. A thoughtless and wellmeant appeal might, alienate sympathy, especially in the case of such as" were wavering, or but mildly interested, or half-inclined to resent. No one who has not been directly involved in the solution of this recurrent problem can appreciate the time and thought put into the conduct of such campaigns with that very potentiality in mind. Many a suggestion which would promise well in the case of a multitude of men is rejected because of a fear that by others it would be misconstrued, or taken in a wrong way by some one here and there. To avoid giving an excuse for an "alibi" on the part of reluctant supporters is one of the most important considerations.

The reasons for failure to participate in this great annual contribution are numerous and vary all the way from the valid to the ridiculously trivial. The valid ones no committee will quarrel with. The trivial ones every committee seeks to avoid raising. The concentration is always on the task of answering the reasons which lie in the twilight zone between, reasons which originally seem sufficient to those who hold them but which are susceptible to treatment by tactful argument. The one reason which lends , itself most readily to such argument is that which apparently actuates a great many men—the feeling that unless one can make a fairly large gift, say from $25 upward, one should not give anything at all.

Nothing could be a greater mistake. It is invariably true, of course, that this fund is supplied in its major portion by the larger gifts; but if it depended on them alone it would invariably fail of its accomplishment, and the vital importance of the great body of gifts of small individual, but great aggregate, amount, cannot be exaggerated. The constant wish of every committee is to find some compelling argument to convince those whose participation must be represented by the smaller sums that such are eagerly welcomed and thoroughly appreciated.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1927 -

Article

ArticleWHAT THE COLLEGE MAN EXPECTS IN BUSINESS

June 1927 By Harry R. Wellman '07 -

Article

ArticleATHLETIC COUNCIL REPLIES TO PRESIDENT HOPKINS

June 1927 -

Article

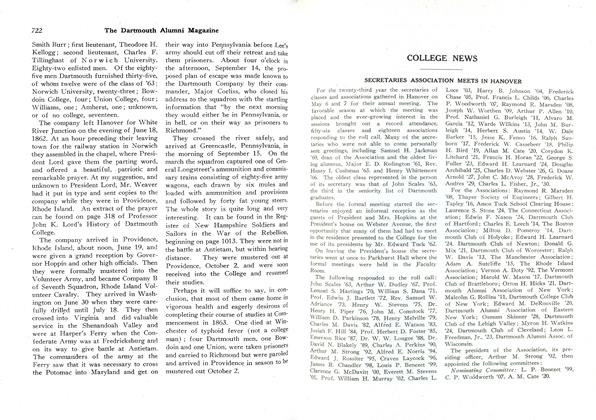

ArticleSECRETARIES ASSOCIATION MEETS IN HANOVER

June 1927 -

Article

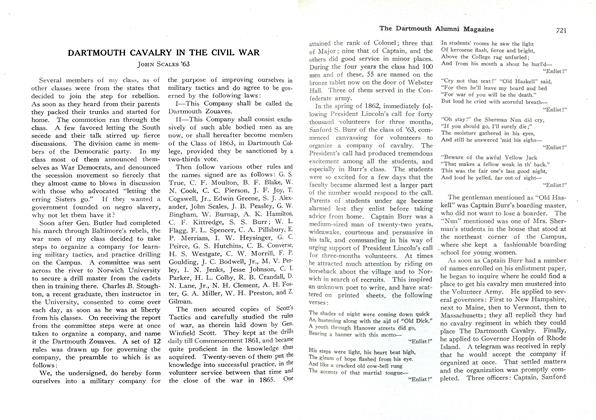

ArticleDARTMOUTH CAVALRY IN THE CIVIL WAR

June 1927 By John Scales '63 -

Article

ArticleCAN CHINA SURVIVE

June 1927