For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

COLLEGE JOURNALISM

THESE has come the complaint generally from the alumni of all American colleges that the editorial tone of college newspapers is not in keeping with the serious responsibility which should be assumed by the men who represent the campus in print. Discussion of trivialities, a flippant disregard of conventionalities taken seriously by an older generation, an assumed position of boredom and ennui toward serious things in life, a "smart alec" indifference to the thoughts and feelings of other people—these are some of the charges lately brought against the college editors. Now and then they are actually charged with viciousness or ill will, and a perusal of some of the editorials in the larger college journals might well lead the reader to some such conclusion. Undergraduate editorials do often contain some rather vicious digs at conditions as they exist; and once the editor is led to believe that such conditions are the result of the planning of an older generation, he seems all the more eager to attack them.

One should recognize that there is a distinct reason for the present tone in college journals, however, and while it may not be an extenuating reason it is still a reason. It is chiefly this: A group of men constituting the board of a college publication find themselves obliged each day to fill a certain amount of white editorial space with printing which shall read like opinion. There may be two, three, or four of these editorials to write and each should represent a subject well discussed. In the first place there are very few newspapers in the whole country, let alone college newspapers, which print stimulating, thoughtful editorials each day. The gift of writing, not occasionally, but continually, editorials which will interest people and make them think is given to but few people in the world. Therefore is it any wonder that a group of men on the editorial board of a college paper often find themselves hard put to it to produce each day editorials which contain definite ideas? Editorial ideas come only with reading, mixing with many classes of people, and some contemplation. The college editors are all students. With the amount of reading to be done in college courses they do not have the time and zest for reading the current magazines and newspapers that editors of regular journals must read. They make this work a sideline.

In most cases no college credit is given for the amount of reading necessary for the production of editorials. Therefore the reading isn't done and the editorials are frequently shallow as a result. The young editor's life is a rush. The curriculum in any American college is taking up student time increasingly. The football man finds himself obliged to work even harder at his studies than the non-football-playing man, because of the enormous sacrifice of time given over to afternoon practice all through the football season. The editor of the college paper faces this same program, not only for three months, as in the case of the football man, but for the whole year. No newspaper will run itself; and the college editor and his board find themselves obliged to get out the paper each day and at the same time fill it with editorial opinion—and yet also keep up with their studies.

Which is sacrificed, studies or editorials? It's usually the editorials.

When there is a lack of ideas in any editorial office the easiest way in which to fill space is to attack something. The object of the attack matters little. All that is necessary is something already in existence, and a Menckenesque manner. One needs neither ideas nor much skill to imitate Mr. Mencken. It has been definitely proved that college editors prefer constructive editorials if such are available, but the amount of work involved in a constructive editorial policy is one that undergraduates under the present system have but little time for and perhaps understanding. A recent editorial in the Dartmouth entitled "Ho-Hum" quite expresses the "tired feeling" attitude assumed by an editorial writer who has nothing to say. The editorial policies of all college publications doubtless need sprucing up, and it is safe to say that in the future, both at Dartmouth and at other colleges, the system will allow future development and improvement.

As the case stands now, college journals are the only activities left in student hands. Athletics are in the hands of alumni and graduate coaches; dramatics are handled by a paid coach and faculty; debating has become part of the curriculum. Is it not possible that the future may bring some kind of professional help to the men who direct student opinion? We have long speculated over the possibility of a course in practical jour- nalism, with the Daily Dartmouth as laboratory work, under some man who knows the game.

Probably more men than ever before have represented Dartmouth on the football field this year. The spirit with which the substitutes have played makes one wish that more men could always have a chance.

AN AVOIDABLE WASTE?

REQUIRED attendance at chapel and other religious services has been abandoned at Dartmouth for two or three years in favor of purely optional attendance. The reasons assigned have been primarily the indifference of young men toward such services, producing restlessness and unseemly conduct when forced to attend them, plus the further fact that in point of numbers the capacity of the chapel had been outgrown. The greater stress, however, has been laid on the former reason and on the feeling that no spiritual good really came from requiring young men to attend chapel.

The natural result has followed, in that the number of undergraduates to be seen at either the daily chapel services, or the vesper services on Sunday evening, has dwindled to the point of being negligible. This was expected, of course. It could hardly be otherwise. The atoning satisfaction was supposed to be the feeling that those few who did come would be religiously and devoutly disposed.

Alumni sentiment toward this matter is naturally divided, but one suspects a preponderance of regretespecially among such as return to Hanover occasionally and observe the great open spaces in the familiar edifices which of old were thronged. There is a vague feeling that a large unit in the College plant, ably manned and capable of doing infinite good, is going to waste chiefly for the lack of soil in which to broadcast the seed. True, much of the soil would be stony ground; but one finds it hard to believe that it would be so utterly obdurate as never to receive, in spite of itself, some impulse toward finer feelings. Even the indifferent hearer is capable of being arrested by a thought, forcibly phrased, which may change the aspect of life and its meaning.

Of course it is deplorable that there be indifference among young men toward the spiritual side of their natures, but on the whole it is open to doubt that their failing in this regard is confined thereto. There is more or less of the same attitude toward, let us say, mathematics, or other required subjects—yet it is not as yet argued that this would best be dealt with by offering purely optional courses, designed only for those who would probably obtain the maximum of benefit. There is in many of us a lurking regret that this step had to be taken—an inescapable doubt that it really had to be taken—as well as a certainty that one of the most potent influences for the upbuilding of youthful character is at present wasting itself on thin air.

Perhaps we got discouraged at just the wrong time. It isn't easy to formulate what we have in mind, but there is room for the suspicion that we are conceiving of religion as if it had suffered no change whatever from the days when dogmatic theology was quite generally regarded as its vital essence. Regarding it in that light, one may admit the hopelessness of attempting to interest the present generation in it. The trouble is that this isn't the fact at all—for religious teaching is as different as possible now from what it was when good old Dr. Bartlett taught "Evidences of Christianity" to young men quite as skeptical as any now in college, or when good old Dr. Leeds held forth of a Sunday to somnolent students, whose thoughts, such as they had, were otherwhere.

Now the appeal of religion may be emotional rather than logical, although not on that account the less real or the less helpful. Admittedly the inspiration of its music, its poetry, its appeal to the better nature, would be assisted if Rollins chapel were not such a gloomy cave—one suspects that, precisely as the young men have responded so eagerly to the lure of the Baker library as an incentive to seeking the companionship of books, they might, in a really inspiring temple, consider with better heart the ministrations of the spiritual. But what we are really getting at is the thought that perhaps it is just as wrong to exempt indifferent students from a consideration of religion as it would be to exempt them from the enforced consideration of anything else.

Compulsory chapel never did any harm, whether or not it ever did very much good. One suspects that it did more good than was usually suspected—certainly that it did quite as little in 1900 as in 1926. With the infinitely better equipment for interpreting the spiritual that exists today, it would not be rash to say the prospeet is better now for doing good than it was in the Gay Nine- ties. Bless you, these students have always been guilty of indifference and have always made chapel a place to do a little frenzied last-minute studying. There's nothing new in that. Whatever is new seems really to be all to the good—a more rational conception of what religion is all about, and of the best ways to awaken men's minds to its beauty, its usefulness, its practical reality as an element in governing conduct. It seems a pity that, just as that was coming to be realized, the colleges should so generally abandon the requirement of chapel attendance. Perhaps, we repeat, we got discouraged at the wrong moment!

Of course, the numbers really are too great for the chapel to accommodate. That argument, at least, was valid enough. It could have been, and still could be, met by requiring attendance only of the two under classesor if possible all but the seniors. What prompts the wish that some such idea might receive official consideration is the apparent pity of wasting such a tremendous agency for good—for good even in the case of the professedly hostile, let alone the merely bored and indifferent, whose conception of what religion really is seems faulty, and due to a vague prejudice born of recollections of the long ago.

A NEW LITERARY CULT

THE book review sections of the Alumni Magazine for November and December show quite strongly the new expressive spirit of the college in the large number of publications by Dartmouth men. The "WheelockNarratives" were the chief Dartmouth publications in the 18th century, while in the 19th the famous "GreekGrammar" of Alpheus Crosby, the Poems of Richard Hovey, and the pioneer critical treatise on American Literature by Professor Charles F. Richardson were among the notable publications. There were other publications, of course—many famous ones—such as the published speeches of Daniel Webster and Rufus Choate, and later of the Hon. Samuel W. McCall. Many alumni will be able to add others to this rather casual list. There was Professor Charles Henry Hitchcock, noted geologist, who wrote more than one hundred papers; Charles Eastman, the Indian, with his stories of the West (translated into French, German, Polish, and Russian); Professor Justin Smith of the class of 'B7, author of the "Troubadours at Home" and a History of Mexico—and many others.

At the present time there seems to be an immense amount of promise in young writers, Dartmouth men of more recent graduation. Tony Rudd's "SecondGeneration" was one of the first novels issuing from the 'Teen classes. It was followed by Leighton Roger's "Wine of Fury" a story of the Russian Revolution. The chief work published in America in honor of the Tolstoy Centenary this year is the play "Tolstoy" by Henry Bailey Stevens of the class of 1912. Henry K. Norton 'O5 has just published a powerful study of the causes of war. A group of younger Dartmouth poets including Marshall Schacht '2B and Alexander Laing '25, are constantly publishing. Ben Ames Williams and Gene Markey have already established themselves in their own fields.

In addition the faculty of the college is engaged in the writing and publishing of more books than any previous faculty has achieved. The growth of a new Dartmouth literary cult is evident. The college has looked too long to one or two men to carry on the literary tradition. The new Baker Library gives every promise of carrying the literary development forward. It has become a cultural center that has found instant utilization. (On the first Sunday night of the college year every bit of available reading space was occupied.) If companionship with books is at all an inspiration to writing and selfexpression, then certainly the future should show an even larger literary output from such a center of culture as Dartmouth where an acquaintanceship with books is made available in the most pleasant way for all students of the college.

MAKING BOOKS FAMILIAR

AN important problem with every man, in college or out, is the one relating.to the use to be made of one's idle time. On more than one occasion President Hopkins has wisely emphasized this as a matter bearing directly on liberal education—the training of minds to make the best possible use of the increment of leisure which modern business and industrial methods are making available to all of us.

Those who have been most intimately in touch with Dartmouth College during the recent weeks have reported an encouraging increase in student interest in books, which obviously springs directly out of the provision of so adequate a place to enjoy them as is afforded by the Baker Library. One must make some allowance for the novelty of it, of course, but the fact remains that here is a new place to go, and also a thing to do, which, if not in itself novel, certainly never had before so inviting an environment in which to do it. If, as seems certain, the coming addition of the Sanborn building devoted to the uses of the English department makes still greater the allurement of good literature, it will be added cause for congratulation.

It ought to be more generally recognized by young men in college that the time for reading is now—not later on, when one will have little leisure for it, but now, while reading is a cognate interest, bound up directly in the business of the moment. The reading which a man fails to do while he has this gorgeous chance is seldom made up in later life, as hundreds of us can testify to our sorrow—indeed to our shame. But we, who knew the College when its library was Wilson Hall, had at least some excuse. One had to love books in spirit and in truth, and must court them in the face of some discouragement. Today the courtship has become a delight, and the response appears to be cordial and spontaneous. That great lounging room with its comfortable chairs, its ash-trays, and its books to be had for the mere taking from a shelf exactly as in a home or a club— how can any sane boy resist its appeal? Indeed there may be some need for renewed insistence on the part of the Outing Club that the true Dartmouth man rejoices in the rigors of the open! Cloisters may become almost too attractive!

WHAT THEY THINK OF US

Lawrence Eager '23—w.h.u.t.t a first issue; it's great. Henry Melville '79—Egad! It's fine. Hon. Frederick P. Garrettson '79—I'm delighted with the new form of the ALUMUI MAGAZINE. It is a work of art. Herbert J. Barton '76—Your November issue is a fine bit of work. E. 0. Grover '94—After all, typography does matter, doesn't it? Matthew G. Jones '23—It will enhance every alumnus' pride in the College. Warde Wilkins '13—Congratulations on the new form of the Magazine. Arba J. Irvin '02—I want to congratulate you on the improved appearance. E. L. McFalls '16—I've been hoping you would be able to make just such an improvement. The new cover is a beauty and the make-up inside is excellent. Howard E. Nutt '90—Your new dress is very becoming. F. H. McCrea '19—A fine looking magazine. It gets my $2. Brooks Palmer '23—Congratulations on new appearance and style. W. H. Middleton, '98—With all due respect I must say I do not like the new format. Not so easy to hold when reading. Charles Taber Hall '03—Just one request. Please do not use too much fine print.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Associations

December 1928 -

Sports

SportsSport for Sport's Sake, and—for Health

December 1928 By Robert J. Delahanty -

Article

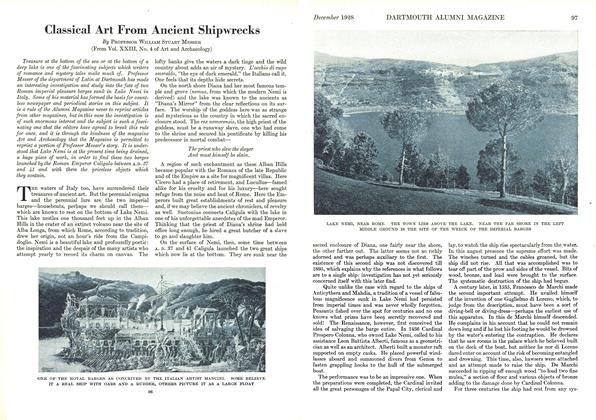

ArticleClassical Art From Ancient Shipwrecks

December 1928 By Professor William Stuart Messer -

Article

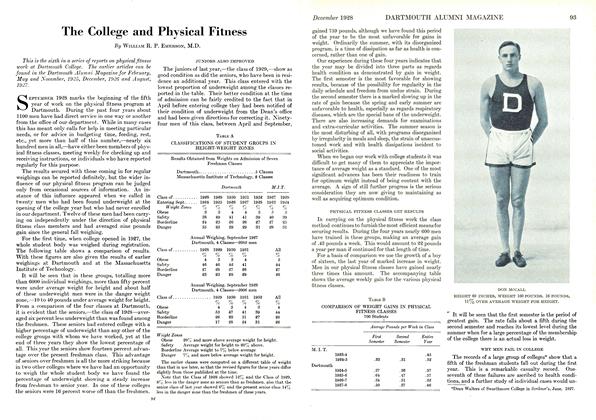

ArticleThe College and Physical Fitness

December 1928 By William R.P.Emerson, M.D. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

December 1928 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

December 1928 By Charles D. Webster,

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

AUGUST 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorBolté Letters

August 1942 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPress

December 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorIn Keeping With This Month's Cover Story, The Review Barks Up Dartmouth's Tree.

MAY 1992 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Geneva

May 1949 By MICHAEL J. DE SHERBININ '42